Refusals in Chinese

Activities (Lesson Plans)

Bargaining Strategies in Mandarin

Practical Ideas & Resources

Resources in this section curated by: Hanna LaPointe, Emma Rollo

Tips and Phrases for Bargaining - 讲价 jiǎng jià | web page

This page provides general tips for bargaining in China. There is a description of appropriate locations to bargain - it is acceptable in most places except when there is a sign that says 不讲价 (bù jiǎnɡ jià) or in department stores. The author includes four steps to properly bargain. First, try to visit multiple stores to get an idea of the pricing. Next, do not show interest in an item, because once you show interest, you have less bargaining power. Third, you can ask for anywhere from 30% to 50% off the price in small markets near tourist areas. Finally, if you want an item but can’t reach an agreement, walk away. Most of the time, the seller will call you back with a new offer. The article also offers some key vocabulary for bargaining.

The Mandarin Learner’s Guide to Haggling | blog post

This blog is a good introduction to the vocabulary and behavior to adopt when bargaining in China. It offers learners “10 keys to success” when haggling in China. The first two are about using correct vocabulary; specifically, emotive language such as “It’s so…!”. Befriending the seller is a good way to get a better discount. If you strike up a conversation with them or become a regular at their shop, they are more likely to give you a better discount. Additionally, the key to bargaining in China is to be polite, such as using the polite form “您” to address the seller.

UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPT OF ‘GUANXI’ | WEB PAGE

This web page is about the concept of 关系 or relationships in China. The author states that 关系 is the key factor to successful negotiation, which may seem overdone to westerners. The key to cultivating 关系 relevant to bargaining is having a general knowledge of China and making a conscious effort. If you show the seller respect and make an effort to get to know them and their product, thus cultivating a positive 关系, they will be more likely to lower the price for you, and you could even become a regular at their shop. This would benefit learners because 关系 is different from simply being polite; they may have trouble getting the hang of it at first. Also, since it is key to bargaining, if learners know how to cultivate 关系, they will have an easier time bargaining.

Lesson: Beginner Mandarin Chinese Phrase "Give Me A Discount" | YouTube video

This video on beginning phrases for bargaining would be helpful to show learners.

In addition to introducing vocabulary, the instructor does two role-plays that show the phrases in action. Learners can observe exactly how they can use the vocabulary. They can also follow along with the dialogue at the bottom of the screen throughout the roleplay.

SURVIVAL GUIDE TO CHINA: HOW TO BARGAIN // 怎么在中国市场讲价 | YOUTUBE VIDEO

Lena, who has lived in China for 5 years, describes her experience bargaining as a foreigner. This video would be especially helpful for learners to watch because they could be in a similar position. She mentions a few tips for bargaining better, such as establishing the 关系 or relationship with the seller, being polite, and using even a little bit of Mandarin. She suggests thinking about bargaining as a mission where you pick a price that you are not willing to go over. Mentioning that you are a student is also helpful - use that as the reason you do not have the money to pay full price. However, if the seller asks for 170Yuan and your “goal” is 150Yuan from an 800Yuan item, go ahead and accept. That way both of you win and you still get a steep discount.

Beginner Chinese EP11: How to Bargain in China | YouTube video

This video introduces money, basic bargaining phrases in Chinese, and some grammar points that would be useful when bargaining.

This video would be helpful for learning or reviewing the different denominations of Chinese money. It could also be a good video to show learners as a way to review basic phrases that they may already know and connect them to bargaining.

the Art of Bargaining in China - Strategies & Tips | blog post

In his blog post, Mike, who has been to China multiple times, writes about enjoying bargaining. He writes about many aspects of bargaining, including whether or not it is ethical. Many foreigners are too scared to bargain and might even feel as though it is useless. Mike labels this as “first-world guilt”. This might be a useful tool for learners because there are not many discussions about the ethical aspect of bargaining. It is likely that learners already have certain opinions on bargaining. Mike also lays out bargaining in a multi-step list, which could be a useful template for learners.

Four Negotiation Tips for Bargaining in China | Harvard blog post

Although it is not directly focused on bargaining, negotiation skills in China are explored in this blog post. Two relevant suggestions for bargaining well are: putting a strong emphasis on relationships (this is known as 关系) and being prepared for a long negotiation process. In order to be able to bargain, first try to relate to the seller so that they will favor you. In order to get the best deal, it is important to know that there is a set order to bargaining that often involves 5 or more steps.

BARGAINING IN CHINESE? | ONLINE FORUM

This is a forum where one user is asking how they should bargain when they go to China. This resource is an example of both vocabulary and of people explaining their experiences bargaining. This would be a good resource to show learners, who will find different points of view on bargaining and learn about bargaining in different Chinese cities.

Bargaining for fakes in Beijing, China: it doesn't end well | YouTube video

This video by the South China Morning Post shows the Beijing Silk Street Market. It focuses on the sellers, who are often aggressive in their selling and unwilling to give discounts. The video also features fake products like knockoff Jordans being sold for the same price as real ones. The person who is bargaining realizes this and tries to get the seller to give them a large discount. This video would be good for learners who are interested in going to China to see what they might encounter when shopping. It also would help learners get familiar with the types of sellers that they may interact with.

Silk Street Market 秀水街市场 | YouTube video

In this video, Bohan, a Polish Youtuber in China, goes to the Beijing silk market and bargains for various items. This would be a good video to show learners as an example of someone bargaining. Bohan focuses on the actual transaction rather than vocabulary and suggestions. He first asks the price of each item, then makes an evaluation, typically saying “too expensive!” Then, he proceeds to bargain with the seller. He is friendly and is even laughing with the second seller. This video shows that it is possible to have fun while getting the best price, which should be the goal for learners.

China It Out | Buying Fruits & Bargaining Tips | YouTube video

This is a video about buying fruits and how to bargain for them. This is an example of how there are many things that can be bargained for besides clothing or accessories. The woman in the video, Rachel, introduces us to different types of fruits that are typically available and then bargains for them.

Refusals in Chinese

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Jaidan McLean

How to Politely Decline an Invitation in Chinese | Blog Post

This brief, yet thorough TutorMing article gives five key phrases for refusing an invitation. Included with the phrases are descriptions of what specific characters in each example mean, as well as cultural explanations associated with the phrase. For example, one of the invitation refusals that this page provides is 改天吧 (gǎitiān ba; ‘next time’) which the author explains is a refusal that is subtly declining all future invitations in addition to the one in a potential exchange. This sort of pragmatic information is critical when teaching a language, but is not always incorporated into the grammar and vocabulary of the classroom.

Title | How to Reject an Invitation KINDLY in Chinese | YouTube Video

This video by Chilling Chinese on how to refuse invitations is super useful for any level of learner. The curator of this project has been studying Chinese for almost four years now, and still has a lot to learn because even simple “how to” videos like this are still teaching them more and more all of the time. The video here includes multiple refusal phrases with the text on screen and the host saying them, in addition to the phrases being included in the description for easy access. The host, Karen, breaks down chunks and characters of each phrase in their specific meaning and how it relates to the refusal, because multiple specific situations such as refusing a service to refusing a request are described.

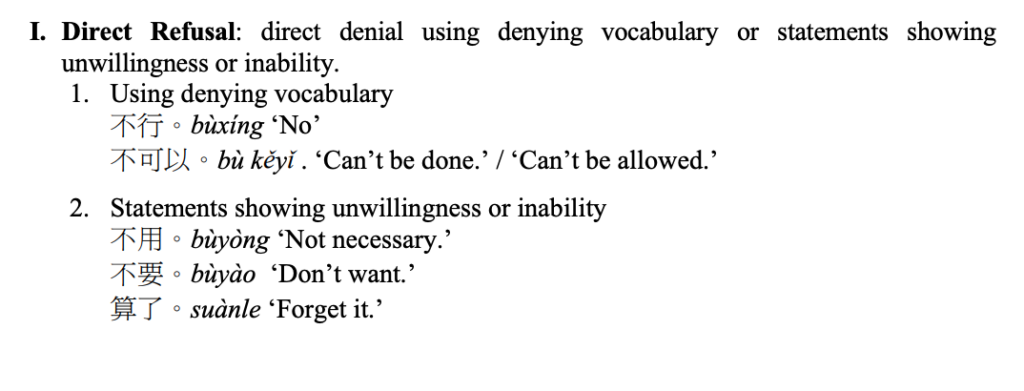

Chinese Refusals | Article

The CARLA website is an incredibly useful source for getting an easy-to-understand breakdown of pragmatic function, and this page on refusal strategies in Chinese is no different. The Chinese refusals page includes a description of refusal types based on the directness as well as additional pragmatic features. More specifically, refusal types are divided into two categories, substantive and ritual refusals. Ritual refusals are almost always obligatory in Chinese where speakers should refuse multiple times before accepting. Substantive refusals are the type where a speaker’s intention is to actually say “no” in a negative response. This page explains the refusal strategies much more in detail, as well as include many useful examples of their use in Chinese.

10 Ways to Say No in Chinese Nicely | YouTube Video

This short YouTube video offers ten ways to nicely reject a request in Chinese. The video includes the ten phrases, as well as a Chinese speaker repeating each refusal. The focus on a request is a useful aspect of this video because learners can use it to easily access a list catered to that exchange rather than having to skim through for request refusals amongst compliments, invites, offers, etc. study from or reference in the future for refusals.

Travel in Chinese Lesson 34 Peking University CCTV News CNTV English | DailyMotion Video

The Travel in Chinese lessons are part of a 15-minute broadcast that used to come on in the early 2000’s on China Central Television (CCTV). Although the lessons were broadcasted on CCTV-9 in China, the segments are widely used by Chinese instructors and learners. This particular video focuses on appointments, but includes an exchange between one of the main characters and her old classmate. In this exchange, two compliments and indirect refusals are given at timestamp 1:40-2:00. That segment of this clip is used in the activity provided under the “Activity” tab at the top of this website.

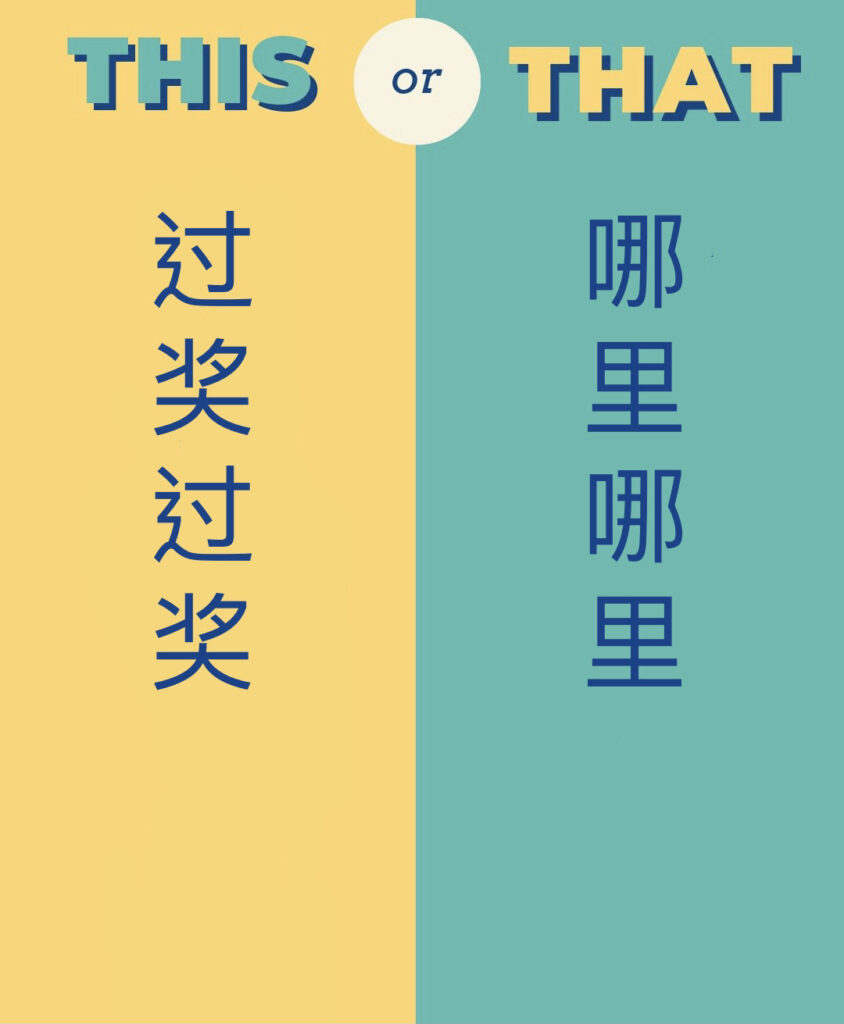

Chinese Words You Learn That We NEVER Actually Use | YouTube Video

Compared to the Chilling Chinese 2018 video (seen toward the top of this page), this video is a more informal one that breaks down certain misconceptions of phrases commonly taught in the classroom but are never truly used by L1 Chinese speakers. The video is entertaining while also informative as it covers quite a few pragmatic functions that instructors could discuss or use in their classroom. Specifically from timestamp 2:07-2:33 is the part of the video where the host discuss refusals, specifically 哪里哪里 (nǎlǐ nǎlǐ).

Don’t compliment a Chinese unless you want to get insulted | TikTok

The 20 second TikTok from @candiselin86 shows a comedic, yet accurate depiction of compliment refusals in Chinese. The video creator is a speaker of both Mandarin and Cantonese and offers many cultural tips on her account. This video in particular was chosen to be used in the assignment included in this curation project under the “Activity” tab. Although the video was initially made to show how Chinese speakers may seem “rude” by their persistence to refuse a compliment, it acts as a useful example of different refusal strategies. In the video, the “character” uses multiple refusal strategies, such as a direct “no,” giving an alternative reason to downplay the compliment, and finally the “you need glasses” refusal that the creator is implying could be offensive.

Common Refusal | Image

Dr. Jean Wu is an upper division Chinese instructor at the University of Oregon, who focuses on pragmatics and L2 curriculum development. 吴老师 (Dr. Jean Wu) is this curation project’s current Chinese instructor, so the two had a conversation in class on Chinese refusals. She explained that the sort of “catch all” refusal that is so commonly taught, 哪里哪里, actually is not appropriate to use with minus social distance situations, such as with a teacher or employer. A much more appropriate minus social distance refusal is 过奖过奖, which means “you overpraise me” and is a more humble response than the directness of “no way” (哪里哪里). Along with this, 吴老师 adds that responding with 过奖过奖 will be seen as more impressive than 哪里哪里 because it shows a deeper cultural and pragmatic understanding of Chinese.

How Chinese People Say “No” in Various Ways | Blog Post

This Dig Mandarin webpage explores “real” and “ritual” refusals, while also giving specific examples of types of refusals. In other words, the page breaks down refusal types into four specific categories based on what they are refusing: invitations, offers, unsolicited suggestions, or requests. Since many sources of refusals in Chinese focus on compliments, this page is really useful in learning additional refusal exchanges that occur and how to approach them. In addition, audio clips of each example are available alongside the written phrases for language listening skills and accessibility. The photo included shows examples of refusals that are “real” rather than “ritual” in which the speaker is truly giving a negative response rather than an intended “yes” with the culturally obligatory “no.”

Saying “No” in China | Blog Post

It comes as no surprise that an article from The China Culture Corner primarily discusses the cultural aspect of saying “no” in Chinese. More specifically, this article explains six refusal strategies from the perspective of culture. These six strategies are expressing embarrassment, being purposefully vague, making excuses, telling “white lies,” putting things off, and offering a positive before a negative. Although these are more methods of refusal than actual linguistic strategies, the theme of these methods of saying “no” continue to relate back to saving face and maintaining respect from others.

Responding to Compliments 哪裡哪裡!| YouTube Video

The short video discusses the use of 哪里哪里 (nǎlǐ nǎlǐ; ‘where where’) which has been a commonly taught phrase in many Chinese foreign language. classrooms. The video also offers a few other compliment refusal phrases, which are accompanied by the two hosts conversing with each. The audio and visual aspects to the phrases is a beneficial part of the video, however many note in the comments of the video and research will agree that the video’s lesson is outdated in promoting 哪里哪里 over more appropriate refusals. This video can still be used in varying ways though, such as acting as an example for learners to critique or compare to other sources.

5 Ways to Deflect a Compliment in Chinese | Blog Post

This Yoyo Chinese page discusses five strategies, to appropriately deflect a compliment in Chinese. The five described are feigning surprise, deflecting, sharing credit, returning the compliment, and disagreeing. Each of these strategies includes several examples of appropriate phrases to use in refusing a compliment. Along with the examples is a short video on the denial culture of “accepting” a compliment in Chinese. The video offers another approach at explaining the aspect of saving face in Chinese culture, and how it influences compliment refusals.

How Chinese People Actually Say "No" | Blog Post

Unlike the other Yoyo Chinese article written by Julie Tha Gyaw (see Gyaw 2014 under “Chinese” tab), this webpage explains Chinese refusal techniques in a way that is much more accessible to a lay reader. The page is written in a way that is describing what “you” as a non-Chinese speaker would receive as a refusal, rather than the webpage being written with the intent to teach the audience specific refusal phrases in Chinese. This difference is really useful for beginners, especially since each refusal situation presented is accompanied by a description of an example scenario, “what it actually means,” and a tidbit about the pragmatics of the refusal phrase.

Chinese Culture: Losing Face 中国文化;丢脸/有没有面子 | YouTube Video

This YouTube video on losing face in Chinese culture by user Lena Elsborg is great for Chinese learners to watch because it showcases real-world experiences of situations in which appropriate actions or phrases are not used. This video serves both as a learning opportunity from the creator’s mistakes, as well as a learning tool for explaining the important concept of maintaining 面子 (miànzi; ‘face’) in Chinese culture. Although no explicit pragmatic tools for refusals are explained in depth, the video can be used for adding a cultural aspect to instructing or learning Chinese.

Academic Resources on Bargaining in China

Resources in this section curated by: Hanna LaPointe, Emma Rollo

Ackerman, D., & Tellis, G. (2001). Can culture affect prices? A cross-cultural study of shopping and retail prices. Journal of retailing, 77(1), 57-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00046-4

This article describes the differences between buyer culture in China and America. China is a buyer-oriented market; Chinese people are typically more frugal than Americans. This partly explains why bargaining is so prevalent in Chinese society and why some American learners may have difficulty assimilating into the culture. This article can be beneficial in introducing learners to the idea of bargaining and how ingrained it is in Chinese culture. The authors of this article also describe how culture can drive down market prices. Since Chinese culture is more frugal, prices have gone down, yet the culture of bargaining still remains.

Fang, T. (2006). Negotiation: the Chinese style. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(1), 50-60. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620610643175

This article focuses on the strategies of Chinese business negotiation. Although not directly related, bargaining is still a type of business transaction that has similar rules and codes of conduct. The author introduces “The 36 Chinese Stratagems”, and although not all of them are relevant, many of them give insight into how and why bargaining is a large part of the markets in China. Two that might be beneficial to learners learning how to bargain are: “Take advantage of opportunities as they appear” and “Hide one’s ambition in order to win by total surprise”. Both of these are key to bargaining, especially the second. It is easier to bargain in the market when the seller does not know your intentions or motivations for buying.

Myers, D. (1993). Teaching Chinese Negotiating Style through Examination of Key Chinese Categories. [Conference paper]. Annual Eastern Michigan University Conference on Languages and Communication for World Business and the Professions, Ypsilanti, MI, United States. https://www.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffiles.eric.ed.gov%2Ffulltext%2FED404846.pdf&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AOvVaw2sN8tcJOsYHUKD-PWSzvwR

This paper focuses on the semantic meanings and polysemy of many Chinese words - the same word can have multiple definitions in a given context. The author connects this to the Chinese idea of time in relation to negotiations. He mentions that in China, time is seen as cyclical and since time is always coming back around, there is no such thing as wasting time. This is crucial to negotiations because people in China are willing to spend much more time negotiating, while many Westerners are not. It is important that learners understand this concept because if they know how to use these multi-meaning words and are able to withstand the long bargaining ritual, they will be able to bargain more effectively in a Chinese market.

Orr, W. W. F. (2007). The bargaining genre: A study of retail encounters in traditional Chinese local markets. Language in Society, 36(1), 73-103. doi:10.1017/S0047404507070042

Four essential acts to bargaining in a Chinese market are discussed in this article. First, it is acceptable to counteroffer by simply responding with a different price. Second, it is acceptable to exaggerate feelings about the price by using expressions like “Wow!” or “So expensive!”. Third, silence can be seen as a rejection of the offer and a new offer will often be presented. Fourth, face-threatening acts, such as commenting on quality often receive more negotiation. It is important to note that salespeople play a minimal role and most of the bargaining will come from the buyer's offers or comments. These acts are based on both social distance and power. They will be beneficial to introduce the learner to bargaining because they are simple, yet specific examples of how a native speaker of Chinese would bargain.

Pang, C. L., Sterling, S., & Long, D. (2015). ‘Mei nu, mei nu, tai gui le!’: to use or not to use Chinese language in Beijing's Silk Market. Language and Intercultural Communication, 15(2), 267-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.993323

The authors of this article focus on the social aspect of bargaining in a Chinese market and how learners can be perceived during the bargaining process. There is a certain ritual to bargaining, so learners should understand specific communicative practices to participate. Many learners mention that you must be aware of how you are perceived in order to be able to bargain better. In other words, recognize how the seller will see you and use it to your advantage. They also mention that speaking Chinese is essential and you should avoid using English, even when the seller tries to speak to you in English.

PS Fong, C. (2013). Retail bargaining in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 25(4), 674-694. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2012-0086

This article can be useful when creating activities centered around bargaining. It focuses on the relationship of power between the buyer and seller. The author identifies four sources of power in the marketplace: the motivational investment, familiarity, the presence of shopping companions, and bargaining disposition. Each source of power could have a different outcome when the learner is bargaining.

Motivational investment is the value that the consumer attaches to the target transaction. The more motivation they have to close the deal, the less power they have over the seller. If consumers have familiarity with the product and believe that they can find a better alternative, they are less dependent on the seller and likely to demand a greater discount. In this case, the buyer has more power than the seller. The presence of shopping companions typically means the consumer spends more time and money, however, they have more power than the seller because they are able to form a team against the seller. Finally, individuals have different views of bargaining. Those with favorable views will have more power over the seller and those with negative views will have less power.

Seng Woo, H., Wilson, D., & Liu, J. (2001). Gender impact on Chinese negotiation:“some key issues for Western negotiators”. Women in management review, 16(7), 349-356. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006116

This article discusses the differences in negotiation styles between women and men in China. The study found that women were often covertly in command, and when they were, they shared the power with their male counterparts. However, when the men were in power, they had sole control over the negotiation process. This might be useful for learners to know so that they can find a way around this gender imbalance. It also gives a more realistic outlook on the bargaining process, and may particularly help women to look out for this situation when they are bargaining in China.

Sternquist, B., Byun, S. E., & Jin, B. (2004). The dimensionality of price perceptions: a cross-cultural comparison of Asian consumers. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 14(1), 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/0959396032000154310

These authors studied and compared Korean and Chinese shoppers and their shopping perceptions. Most relevant to bargaining are two values: price consciousness and sales proneness. Price consciousness describes how strongly a consumer wants to pay the lowest price possible for an item, while sales proneness is how strongly a consumer will buy a product based on its price. Korean shoppers tend to be more price-conscious and prefer sales that can be achieved via their bargaining skills. This article sheds light on the motivations behind Korean shoppers’ bargaining behavior, rather than simply explaining that it is a common pragmatic function.

Uchendu, V. C. (1967). Some principles of haggling in peasant markets. Economic development and cultural change, 16(1), 37-50. https://doi.org/10.1086/450268

This article focuses on the general ideas of when it is acceptable to haggle in markets and how to do it. Haggling is a structural behavior system and the more you follow it, the more likely you are to be successful at it. There are two key principles that are mentioned in this article: there is a set range of prices that are acceptable to offer and one should know where to haggle. Learners must know the set range of prices to haggle and if they exceed this range, the seller may react with frustration, anger, or even amusement. This is a representation of the power and social distance that the buyer and seller have. Knowing where to haggle is also essential; if the place has a small number of customers, it is acceptable, if it is a chain or large-scale store, it is not acceptable to haggle.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON REFUSALS IN CHINESE

Resources in this section curated by: Jaidan McLean

Ma, R. (1996). Saying ”yes” for ”no” and ”no” for ”yes”: A Chinese rule. Journal of Pragmatics 25, 257-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)00098-0

The research done in this study focuses on the “contrary-to-face-value” or indirect messages pertaining to the pragmatics of refusal choices in Chinese. In other words, this article goes beyond a textually-based approach to refusing in Chinese that L2 learners are often taught to take, rather than a contextually-based approach. This article specifically discusses Chinese L2 pragmatics in the perspective of Anglo-American English speakers.

Based on the importance of saving face and keeping respect in Chinese culture, this article presents and identifies the “contrary-to-face-value communication” (CFVC) following two cultural motivators. The two cultural motivators are explained as the internal motivation of who the refusal will be serving, and the external speech of actually saying “yes” for “no” or “no” for “yes.” Four contexts with forms of CFVC are analyzed in this article, with explanations for the intended audience of Anglo-American English speakers on the Chinese culture of saving face.

Ren, W., Lin, C. Y., and Woodfield, H. (2016). Variational Pragmatics in Chinese: Some insights from an empirical study.

One takeaway from this article is that pragmatics on refusals vary on the Chinese spoken; whether Mainland Chinese, Taiwan Chinese, or Singapore Chinese. The study takes this Chinese variation and analyzes it using their refusal strategies as English L2 students. Although this study also involves students studying abroad and their English refusals, this study is not categorized under the “English” tab of this curation project, because the ultimate discussion of the study focuses on the socio-pragmatic variation of the Chinese-speaking regions.

In specifically discussing the Chinese variation, the authors compared the findings of direct and indirect responses given as well as the explicitness of the compliments used in the data collection. To summarize, the study found that Mainland and Taiwan Chinese speakers both preferred indirect refusals, as well as found that there actually was not a significant regional effect on the choice to refuse or not. And although this article did not present new information on Singapore Chinese with their study, the article does compare this finding of no significant effect to previous literature that found a significance in Singapore and Taiwan Chinese.

Yang, J. (2008). How to Say ‘No’ in Chinese: A Pragmatic Study of Refusal Strategies in Five TV Series. Proceedings of the 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20) 2, 1041-1058. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University.

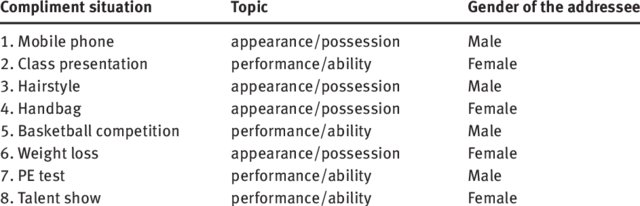

This publication presents a study done in a more fun and unusual way than others included in this curation project. The study looks at 160 video clips from five Chinese television series, 青鳥的天空 ‘The Sky of the Green Bird,’ 青春不解風情 ‘Youth does not understand the amorous feelings,’ 慾望 ‘The Desire,’ 編輯部的故事 ‘Stories of the Editors’ office,’ and 一地雞毛 ‘Trifles over the ground.’ Using video clips of refusal situations, the authors were able to identify four main exchanges in which refusals were used: request, offer, invitation, and suggestion.

These four types are fairly salient, so they were easier for the authors to narrow down and focus on for their data collection. Due to the large pragmatic emphasis on direct vs. indirect refusals, each TV scene was analyzed for which strategies in what type of situations would be used. The results seemed to be a bit more complex than expected, but makes a useful point in that sometimes individual choices may override the usually expected response, even in the case of TV writing.