Apologies in French

Activities (Lesson Plans)

Apologizing in French

Practical Ideas & Resources

Resources in this section curated by: Mathilde Bégu, Aurélie Bertin, Aleya Elkins

Demander Pardon | Children's Book Excerpt

While the word pardon alone is often used casually as a response for minor, everyday missteps, using it in the longer phrase je vous demande pardon (I beg your pardon) with the verb pardonner causes an increase in connotations of Severity + and Power +.

This excerpt from the classic philosophical French children's book Le petit prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry demonstrates this apology at a pivotal moment in the novella.

The boy, the story's protagonist, is preparing to leave his small home planet where he has been carefully doting on a vain, haughty, and naïve flower. He loves her dearly but her apparent lack of reciprocation leaves him sad and lonely. He says goodbye to the flower before he sets off, but receives no response. After his second goodbye, the flower apologizes, saying j'ai été sotte, je te demande pardon, and je t'aime. Tu n'en a rien su, par ma faute. (I was stupid, I beg your pardon. I love you. You did not know, it's my fault.)

Here, she addresses him with informal tu, but her contrastive use of the more formal phrase, je te demande pardon, suggests a sense of distance between them as they part. It also matches her dramatic speaking style.

Tout l’art de s’excuser, sans trop en faire | Article

This journal article analyzes the different spaces in which apologies occur. According to the author, to apologize is not only an unavoidable act when living in a community, it is also a way to show vulnerability, empathy and overall a humbling act. The article provides concrete examples of situations in which apologies are expected, such as stepping on someone's shoe, bumping into someone, and emailing a boss to apologize for a late reply.

The act of apologizing has many physical and psychological effects on the speaker and the receiver of the apology. The author mentions the bounding and solidifying experience for the speaker to apologize and the receiver to accept the apology, to eventually work together by acknowledging each other's sensitivity and vulnerability. However, there are some limits to the validity of an apology. Sincerity is key - an apology should not only be an act of politeness, but a sincere desire to correct an action.

Pragmatics: Knowing what to say in certain situations | Blog Post

This blog post focuses on how French learners of English and American learners of French at the university level misused expressions related to the function of apologizing. The author analyzes in-class observations around the use of excuse me and sorry with novice learners of English and French, as an attempt to gather information on French pragmatics.

French learners of English used excuse me when they had done something wrong, as well as I’m sorry when they wanted to get the teacher’s attention. The American learners of French overused je suis désolé in a variety of contexts. The main challenge learners need to overcome is the literal translation from their L1 to L2, and the lack of pragmatic resources available for teachers and novice learners.

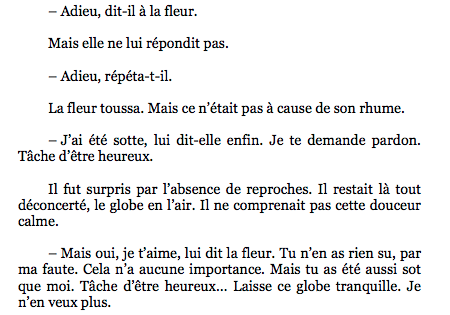

Apologizing to a Friend | Text Message

Here, the responder explains to her friend (Solidarity +) that she is tired because she went to the movie theater late the previous night. Therefore, she was asleep when she received the first text, in which her friend asked if they could talk on the phone. Missing that opportunity is probably not too important, especially because the smiley face emoji in the request indicates the reason for the call is not serious (Severity -).

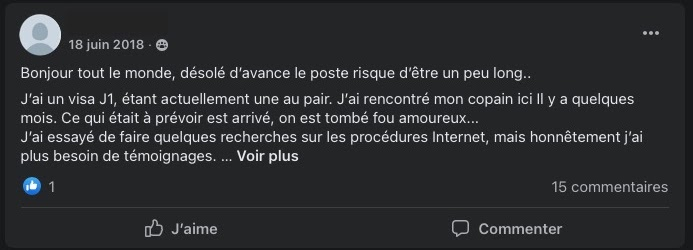

Apologizing to a Community | Facebook Post

Here, the writer apologizes in advance for writing a very long post to a Facebook group. Presumably, the writer feels a sense of connection with the group (Solidarity +), since their post is seeking help and advice on a personal issue. Though the situation for which they need help is important to them, the reason for their apology, writing a long post, could be seen as less severe (Severity -). It is important to pay close attention to the precise reason for the apology when exploring how French apology expressions are used!

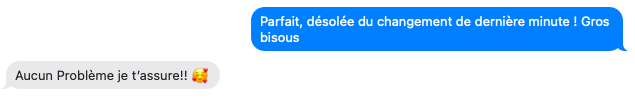

Apologizing to a Family Member | Text Message

The writer uses désolée here when texting her sister (Solidarity +) about canceling a call at the last minute. She apologizes for something that she has done (canceling the call) that influences the other person. The use of emojis and reassuring phrases in the sister's response indicates canceling the call is not a severe act (Severity -).

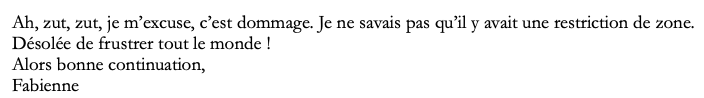

Apologizing to Colleagues | Email

Here, désolée is used to apologize for something that the writer of the email has done which affected others: frustrer tout le monde (frustrate everyone). The writer sent a previous email to a large group of people with a link to a video, but the link did not work. Thus, the writer likely feels bad about wasting everyone's time. This message also employs other expressions of apology: Ah, zut, zut, je m'excuse, c'est dommage (Oh, shoot, shoot, I'm sorry, what a shame). When encountering apologies with more than one expression, think about how combining expressions might change the meaning. For example, how would a Power + expression with a Solidarity + expression feel different than a Power + expression alone?

Apologizing to a Colleague | Email

In this email, the sender expresses an apology to her colleague (Power +) for requesting a change of plans (and possibly for the influence of a personal issue on their professionalism) which affects someone they know professionally. Their urgence bébé (child-related emergency) means they must ask to reschedule their previously planned interview. The Severity may depend on the importance of the interview, but the sender adds the adverb absolument in front of désolée to show sincerity.

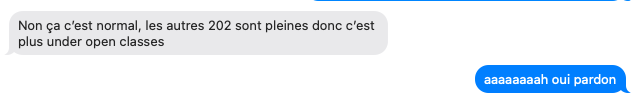

Comprehension | Text Message

This is an example of misunderstanding that has been resolved. The writer who sent the blue text misunderstood previously stated information and shows that she now understands by writing pardon. This use is in direct opposition to the previous usage. The difference between the two can be specified with use of question marks or intonation to show confusion in the previous usage (no question mark is used here, to show comprehension), and as always, context.

Misleading Translation | YouTube Video

In this clip of Ratatouille, Chef Skinner expresses his condolences with the phrase toutes mes condoléances. However, the subtitles say je suis désolé. This is an example of how learners may be misled to think je suis désolé is an appropriate response to someone's death. The subtitles throughout the film misaligned with what was being said, and some of the subtitles felt unnatural. This may be a result of attempting an English-based translation of this film, since Ratatouille was originally released in English.

Typo and Misspeaking | Text and YouTube Video

In addition to more straightforward apologies, pardon is used to acknowledge a simple mistake in typing or speaking.

In the text message, the writer uses pardon to correct a misspelling in someone's name; she did not write "Haley" correctly the first time.

In the video, pardon is used to correct fumbled speech.

Customer Service | Tweet and Video Clip

Je suis navré.e as an apology is often used in customer service communications because of its Severity +, Power +, Solidarity - sense. This short video, showing results from a Twitter search of the phrase je suis navrée, demonstrates how companies and business owners use this phrase as a way to respectfully apologize to unsatisfied customers.

Zou dit pardon | YouTube Video

This video is from the popular animated French children's series, Zou, which follows a 5-year-old zebra named Zou. Like many children's series, Zou has lessons on appropriate societal behavior and expectations. In this clip, Zou learns how to apologize and say pardon after hurting his bird friend's feelings by wrongly accusing him of breaking his toy plane.

What? | YouTube Video

Pardon is also used to signify that you have not understood or heard something being said. In this clip from Confessions d'Histoire, the character uses the phrase Hein? Quoi? Pardon? to ask the speaker to repeat what's been said.

Je m'excuse | Email

In this email, the writer apologizes to a colleague for not responding to her email sooner. The use of tu shows solidarity between the colleagues and an absence of hierarchy in their relationship (Power -). The late reply does not seem to be so important (Severity -). The apology is mostly here to start the email politely.

Interrupting | YouTube Video

Pardon is also a natural word to use when interrupting someone. For example, in this video, the interviewer quickly interrupts his guest to add on to his question.

Note: using pardon to interrupt someone to clarify your words may be appropriate in some situations, but interrupting someone in other contexts might be considered rude. An interruption is not polite simply by using the word pardon.

Pardon mais… | YouTube Video

Here, the use of pardon is meant to apologize for something the speaker is about to say, knowing that the listener will not like the following statement. How do you think this differs from the similar use of je suis navré.e at the bottom of the Je suis navré.e section?

Question de point de vue (Carlito) | YouTube Video

In this video, a woman on the phone apologizes to the person on the line for taking another call. The expression excuse-moi is used, meaning that the two people are presumably friends (Power - / Severity - / Solidarity +) or close enough to use the tu form of the verb.

Pas d'amalgame (McFly & Carlito) | YouTube Video

Here, a waitress apologizes to a customer for staining his shirt. In this context, the vous form of the verb is used to emphasize the Power + / Severity + / Solidarity - dynamic between the two people in the video.

Excuse(a)-moi to get someone’s attention | YouTube Video

Excusez-moi can also be used to get someone's attention, but as the verb "excuser" is conjugated with the pronoun vous, this expression would be heard in context of Power + / Solidarity -. For example, in this video, a customer is trying to get the attention of the waiter (Solidarity -).

Usul: comment séduire après | YouTube Video

The expression excuse-moi conjugated with tu can also be used to get someone's attention, but in context of Power -. Here, the man is asking for the woman's attention. Since the two do not know one another, the speaker is purposefully creating less distance between them by using the pronoun tu (Solidarity +).

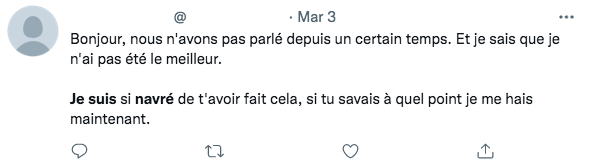

Solemn Apology | Tweet

This tweet is an instance where je suis navré.e is used to apologize for something important. Here, the author wrote the tweet to apologize for having done something really hurtful to another person (Severity +). It looks like the two people used to be friends, but may have had some sort of falling out: Nous n'avons pas parlé depuis un certain temps. Et je sais que je n'ai pas été le meilleur. (We have not spoken for some time. And I know I have not been the best.). The situation seems to be Solidarity - now, so there is some distance between the person who apologizes and the recipient of the apology.

Solemn Apology | Novel

In this passage from the novel L'Urgentiste by Kate Hardy, the doctor tells a little boy “je suis navré” for not being able to save his father from a heart attack (Severity +). Although je suis navré.e can also be used to express sympathy, in this case, the doctor is truly apologizing. It is clear he was actively involved in treating the patient: “nous avons fait tout ce que nous avons pu, mais votre père a fait un arrêt cardiaque et nous n'avons pas pu le ranimer” (we did everything we could, but your father had a heart attack and we were not able to resuscitate). The relationship between the doctor and the boy is Power + and Solidarity -.

Strong Sympathy | Tweet

However, when expressing sympathy, je suis navré.e is used differently! Though it keeps its sense of Severity + (with Severity indicating strong sympathy for a horrible event, in this case), it no longer has as strong of a sense of Solidarity - or Power +. In this tweet, the user addresses their conversation partner with toi (informal tu), indicating they have a Solidarity + and Power - relationship.

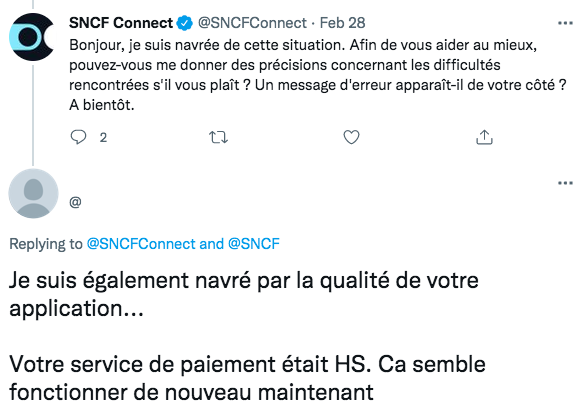

Ironic Usage | Customer Review

However, because this phrase is used so often as a generic customer service apology, it has somewhat lost its sincerity for customers. Here is an example of an unhappy customer intentionally flipping the phrase to use it against the company. After the service representative says “je suis navré de cette situation” (I am sorry for this situation), the customer replies, “je suis également navré par la qualité de votre application” (I am sorry about the quality of your app).

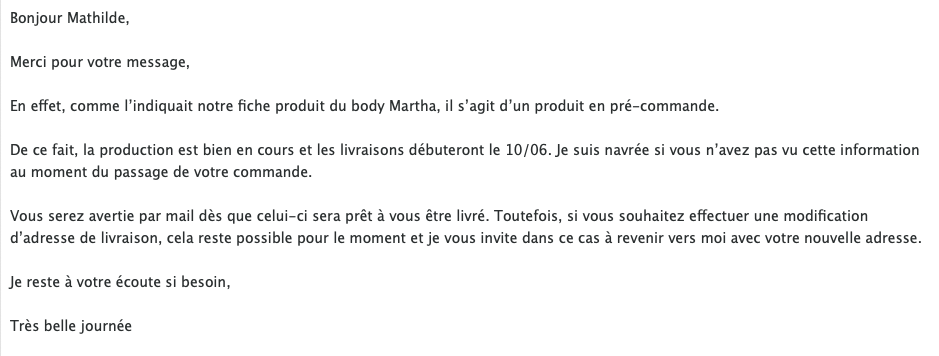

Polite Blame | Email

In general, je suis navré.e does not always signify the user's regret or acknowledgement of wrongdoing, even when it is used in customer service. Here, a seller uses the phrase to suggest the buyer is at fault for not having thoroughly read the product description; the item is on pre-order, and the buyer was unaware, even though the pre-order status was written in the product information. The use of the phrase je suis navrée si vous n'avez pas vu cette information au moment du passage de votre commande (I am sorry if you did not see this information when you placed your order), redirects the blame from the seller to the buyer.

Ironic Malice | Tweets

Je suis navré.e mais (I'm sorry but) can also be used to superficially pre-"apologize" before the speaker says something offensive or malicious, or to indicate disagreement before a speaker says something they know their listener will not like. These ironic usages do not imply the speaker actually wants to be forgiven for their statement, rather, it acts as a way to mark their unapologetic attitude. These usages may also appear as je suis navré.e que (that), si (if), pour (for), etc.

Although I'm sorry in English can also be used ironically, the ability to recognize if je suis navré.e is being used genuinely or not is important for learners as they navigate different phrases of apology. The three tweets here are examples of je suis navré being used for ironic malice.

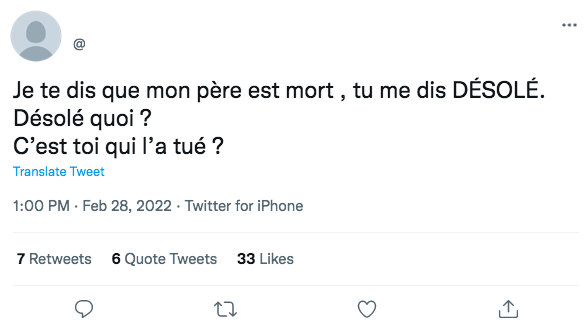

Negative reaction to désolé.e | Tweet

Désolé.e is generally not used to express mourning in French. While it might be appropriate to tell someone who is grieving I'm sorry for your loss in English, a direct word-based translation in French, je suis désolé.e pour votre perte, would be an inappropriate (and confusing) way to express condolences in French; it implies some responsibility for the cause of grief. This tweet is an example of a user expressing a negative reaction to the use of the word désolé.e as an expression of condolences. The question C'est toi qui l'a tué? (It's you who killed him?) demonstrates how désolé.e represents the apologizer has played a role in what they are apologizing for.

Combining Expressions | Tweet

Expressions can be combined in different ways to specify and change sentiments. Here, je suis navrée as an expression of strong sympathy is used in combination with mes condoléances to convey that the writer is greatly saddened that the person to which they are responding has suffered a loss. When analyzing texts online, consider how the use (or non-use) of emojis changes the feeling of the message. How might this example feel different without the added heart? What might the heart indicate about the relationship between the two communicators?

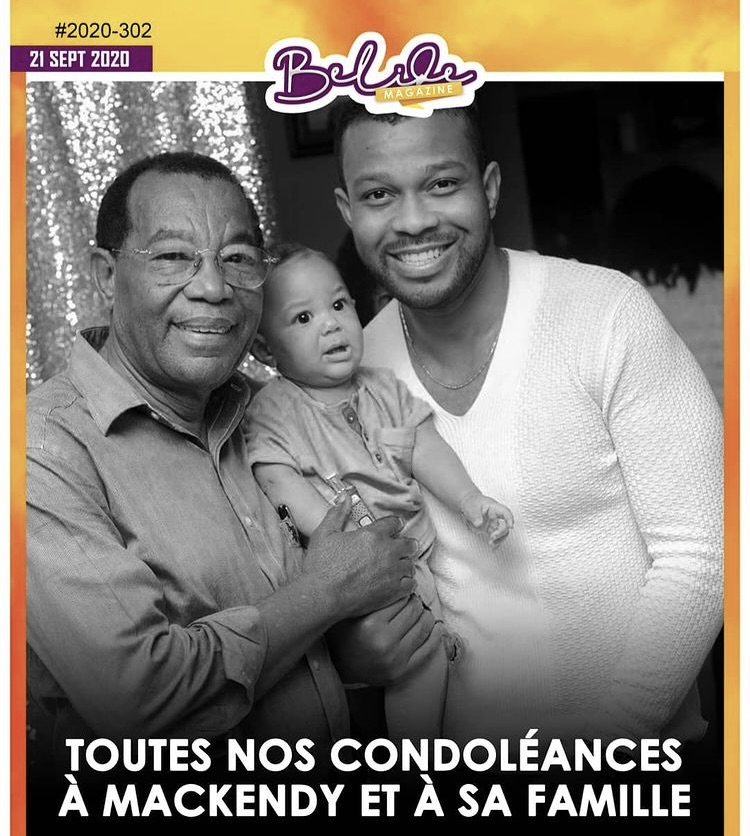

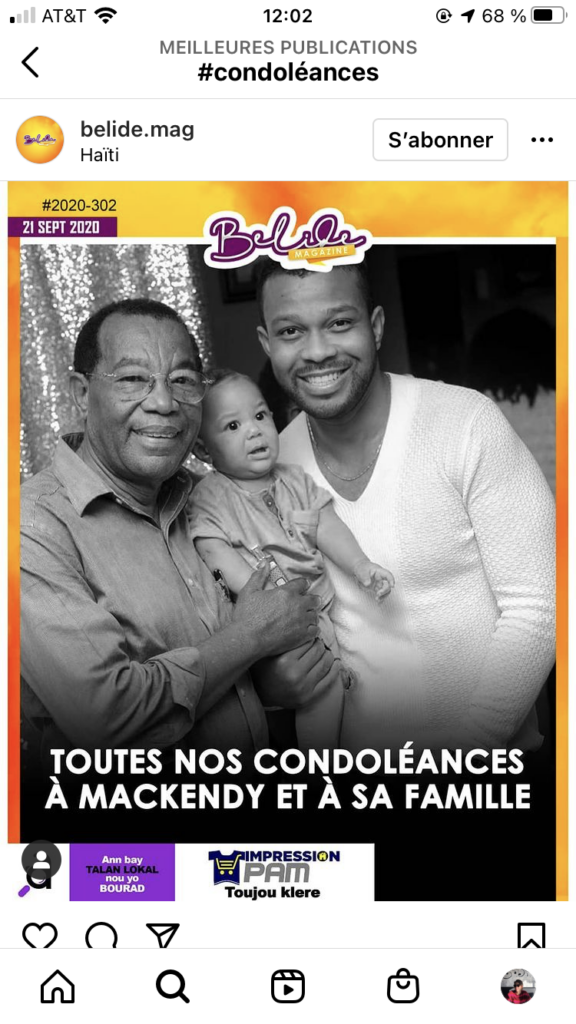

Condoléances | Instagram Posts

Expressing sympathy over someone's death would likely make use of the word condoléances (condolences). This is an example of an Instagram post expressing sympathy to singer Mackendy Talon and his family for the death of his father. This is accompanied by a card one might give to a grieving person.

Academic Resources for Apologizing in French

Resources in this section curated by: Mathilde Bégu, Aurélie Bertin, Aleya Elkins

Beeching, K. (2019). Apologies in French and English: An insight into conventionalisation and im/politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 281-291. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378216618302224

This article traces the evolution of common illocutionary force indicating device (IFIDs) related to the function of apologizing. The study surveys the etymology of expressions like je suis désolé, pardon, excusez-moi, sorry, I’m sorry, excuse me, using a sub-titling corpus of French films and analyzing the subtitles translation for American, British and Canadian audiences.

The study shows that Canadian French uses more intensifiers while apologizing, where French French uses more justifications. Overall, there appears to be a shift towards fewer variants in more recent corpora of spoken French. Additionally, the Quebec data shows a preference for more anglicized choices than the more old-fashioned pardon and regret from the European French corpora. The authors conclude by noting the influence of the translator, who is more influenced by “the semantics of the Source Language etymon (sorry = désolé(e)(s)) than by how the speech act is normally performed in the Target Language."

Borkin, A., & Reinhart, S. M. (1978). Excuse me and I'm sorry. TESOl Quarterly, 57-69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3585791

The use of the English expressions excuse me and I am sorry are discussed in this paper. The authors view these "as [a possible] step in which the offender or potential offender acknowledges something has gone wrong or may go wrong, accepts responsibility of state of affairs, and attempts to make things right". According to the authors, the difference between the two expressions is that I am sorry is not only used to apologize, but also to express sympathy or regret, while excuse me is used to interrupt someone, which is still part of the apologetic function.

The authors argue that miscommunication around these expressions happens between learners of English and native speakers (as well as teachers) - there is a need for a more precise pragmatic instruction in ESL classes. They suggest comparing the differences between the two apologetic expressions in a teaching unit for intermediate level students, who already learned these expressions, but do not know how to distinguish them or use them appropriately. As part of the activities for the lessons, the authors suggest dialogs and role plays.

Center for Applied Research on Language Acquisition (2021, March 3rd). American English Apologies. https://carla.umn.edu/speechacts/apologies/american.html

Even though this web page describes five possible strategies to make an apology in American English, the authors argue that the strategies are available across cultures and languages, but each culture group and/or language might favor one over the other depending on the situation.

In American English apologies are used for a variety of reasons and contexts, but all can fall under at least one of these strategies. The first consists of using an expression of an apology like sorry, excuse me, which are favored orally, as well as I apologize which is more common in writing. These expressions can be intensified with adverbs like very, sincerely, etc. The second strategy is the acknowledgement of responsibility with different degrees of recognition, from the highest level with it's my fault, to the lowest level with I didn't mean to, or even blaming the hearer with it's your own fault. The third strategy is to provide an explanation or account by describing the situation that led to the offense, as an indirect way to apologize for it (the bus was late to apologize for being late to a meeting, for instance). The fourth strategy is to offer repair by providing a payment for some kind of damage or by making a bid to carry out an action, like asking to reschedule a meeting. The last strategy is a promise of non-recurrence where the apologizer commits to not let the offense happen again.

Claudel, C. (2015). Apologies and thanks in French and Japanese personal emails: a comparison of politeness. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 19(4), 127-145.

This article examines how "politeness" is used in thanks and apologies in French and Japanese emails between correspondents based on characteristics like gender, age, and relationship (which maps onto +- power and +- solidarity). The author takes a broader look at the concepts of "politeness" in the two cultures, before exploring how politeness appears in different features of language. Claudel ultimately advocates for a differentiation between "politeness" as a result of personal choice and "civility" as a result of "obligation to respect social norms" (p. 127).

Notable content from the article as it relates to French apologies include observations that: 1. Apologies may be used instead of thanks, for example, "Il ne fallait pas" or "Vous n'auriez pas dû", which denotes a degree of embarrassed apology to the addressee for the benefit they have given, 2. But attention to the speaker/writer tends to lead to the use of thanks, 3. Apologies were absent from emails sent between family, 4. Apologies are more common between student and teacher, and in such cases, the student uses a form marked for distance "Je vous prie de bien vouloir m'excuser", 4. Thanks and apologies occurred primarily in the opening sequence of emails, with thanks reiterated at the end.

Cohen, A., & Olshtain, E. (1981). Developing a measure of sociocultural competence: The case of apology. Language Learning, 31(1), 113-134.

This study focuses on the ability to use appropriate sociocultural rules of speaking, focusing on the speech act of "apology", by reacting in a culturally acceptable way in context and by choosing stylistically appropriate forms for that context.

The findings showed that it is possible to identify culturally and stylistically inappropriate L2 utterances in apology situations. However, all participants were not native speakers of English and the authors acknowledge that judging the nonnative speakers under native standards might have penalized the research. They concluded by saying that speakers of English as a foreign language use, for the most part, the same semantic formulas as native English speakers only when their proficiency level permits it. For lower proficiency levels, the influence of native language patterns was too significant.

Cohen, A. D., & Olshtain, E. (1985). Comparing apologies across languages. In K. R. Jankowsky (Ed.), Scientific and humanistic dimensions of language (pp. 175-184). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

In their cross-cultural analysis, the authors observe young Hebrew speakers who learned English as their L2. They put the speakers in a situation in which they bumped into a woman at a store. After analyzing the responses from the participants, the authors argue that in the case of apologies, there is often a transfer from the L1 to the L2. They refer to "the learners' strategy of incorporating native language-based elements in target language production and behavior." These transfers could happen either because of a knowledge gap regarding L2 social norms, or because the learner does not even think that such differences could occur.

This claim relates to the transfer by English speakers of I am sorry to situations in which the speaker wants to express sympathy in French, that would not require an apologetic expression, possibly resulting in confusion. Thus, pragmatic instruction (such as the IPIC model) is a way to limit transfer from L1 to L2 while educating the learners on the appropriate speech acts to use in the target culture.

Cohen, A. D., & Olshtain, E. (1994). The production of speech acts by EFL learners. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1). doi:10.2307/3586950

The difficulty with the apology speech act is that there are nuances and potential modifications to the intensity or the sincerity of the apology. According to the authors, speech acts are continuously varying since they are conditioned by social, cultural and situational factors. This study investigates the processes (assessing, planning and executing) involved in the production of speech acts in L2 learners. The authors are also interested in knowing if grammar and pronunciation are involved in the production of speech act utterances.

The results show that the majority of participants planned the speech act they would use (apologizing for example), but did not plan specific vocabulary or grammar. It also looks like the language they used to plan their role play was English, which is their L2, although a lot of the participants think in another language as well.

The authors argue that "learners may have a more difficult time in producing complex speech forms than teachers believe, whether they be speech acts or other language forms of comparable complexity". For that reason, planning matters, and teachers should teach learners how to successfully process information. Learners who have time to plan before entering a situation generally show better complexity of language and more vocabulary than learners who do not have that time.

Edmonds, A. (2010b). “Je suis vraiment désolé” ou comment s’excuser en interlangue. In B. de Buran-Brun (Ed.), Altérité, identité, interculturalité (pp. 69-82). Paris : L’Harmattan.

This study examines the use of illocutionary force indicating devices ("mécanisme pour indiquer la force illocutionnaire," or MIFI), which formally indicate the speaker's intended purpose, by native speakers in Southwest France and native English-speaking learners of French. MIFIs are one of the five main apology strategies commonly used in a number of languages. Results indicated that learners were neither more explicit nor more creative than their native counterparts in their apologies (though there was some discrepancy), but they did show exaggeration in their patterns. In other words, learners followed the same patterns as native speakers in the use of MIFIs, but the degree to which they demonstrated the patterns was more pronounced; they amplified subtle differences in usage. Edmonds suggests this is common among language learners, regardless of their native language or language of study.

Edmond's classifications of apology expressions into genres of MIFI was also noteworthy. The author organized the expressions as follows: Expressions de regret (ex : je suis désolé, je suis navré), demandes de pardon (ex : excusez-moi, je vous prie de m’excuser, je vous demande pardon) et offres d’excuses (ex : je m’excuse, pardon, toutes mes excuses). Edmonds also noted that learners seemed to transfer temporal orientation of certain English apology expressions (I'm sorry and excuse me) to their requests for forgiveness and expressions of regret in French, which connects to the consistent phenomenon of native language influence on the studied-language apology system.

Grossmann, F. Krzyżanowska, A. (2018). Comment s’excuser en français et en polonais : étude pragma-sémantique. Neophilologica, 30, 88-107.

This article shows the variety of expressions used to apologize in French and Polish. The authors refer to levels of politeness or formality to explain the parameter of power. They conducted research on the use of apologies in emails sent to parents, friends and colleagues, focusing on expressions that contain the word excuse and pardon.

Their corpus results show that the word excuse is used in the majority of apologies via email, whether politely or not so politely. They also noticed that je m'excuse is used very rarely in emails. The normal forms are veuillez m'excuser or excusez-moi. It is more polite for the writer to ask the reader to excuse them rather than to present their apologies directly. Pardon was also used in emails, but not only to apologize. Indeed, pardon carries different functions such as expressing guilt and regret.

Iftime A. (2019). L'approche de l'excuse dans les manuels de FLE publiés en Roumanie. Revue Roumaine d'Études Francophones, 11, 356-368. http://arduf.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Iftime-2.pdf

This study analyzes the presence or absence of apologies in four Romanian textbooks designed for learners of French. Out of the four, only three mention apologies and define the expressions "je vous présente mes excuses", "je m’excuse", and "excusez-moi" as marks of politeness in French, without explaining how to apologize using each one. Moreover, the analysis shows that apologies are not nuanced in the textbooks (in terms of power, severity and solidarity), but that learners simply have to remember the expressions.

According to the article, the textbooks do not mention ways to apologize implicitly (which is very common in French). For example, recognizing one's offense ("je suis en retard !") would be more of an apology than just saying pardon, and yet, these nuances are not taught in these textbooks. Moreover, in these textbooks, there are only positive responses to the excuses ("ce n'est pas grave, ce n'est pas de ta faute") rather than other negative responses that are also common in discourses.

Finally, this article contains an interesting definition of apologies in French. Kerbrat-Orecchioni (2005) defines an apology as an “act by which a speaker tries to obtain from his addressee that he grant him forgiveness for an offense for which he is in some capacity responsible towards him”. This definition confirms the assumption that apologies in French are truly necessary when the speaker is the cause of the offense (contrarily to English).

Lakoff, R. T. (2005). Nine ways of looking at apologies: The necessity for interdisciplinary theory and method in discourse analysis. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton (Eds.),The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 197–214). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753460.ch11

According to the author, in American English, the single form I am sorry can function variously as an apology as well as a way to express sympathy, and also to deny an apology. By using I am sorry, "an apologizer with power can, by making use of an ambiguous form, look virtuous while saving face". For example, an American speaker who needs to apologize in a public space could easily use I am sorry as a legitimate and accepted apology, even though he might not mean it.

Thus, we can see that the functions of apologies differ in French and in American English, confirming the need for clarifications of apologetic expressions for American learners of French.

Sanae, H. (2007). Pour une discussion métapragmatique en classe de FLE. Revue japonaise de didactique du français 2(1), 53-70.

This study shows the difference in apologies between Japanese and French speakers, which often leads to confusion in the L2 French classroom in Japan. The author researched the way that apologies were introduced in four French textbooks and noticed that only a few expressions (pardon madame, excusez-moi !, and oh pardon !) were mentioned. Similarly to the research done by Iftime (2019), the apologies are not very contextualized in the French textbooks, and there are very few examples of speakers arguing.

The author also looked at French textbooks used in France, highlighting that the apologies were mentioned more often, and presented in authentic dialogs. Another interesting difference is that the apologies in the textbooks in Japan always happen between friends, whereas they happen in various contexts in the textbooks used in France (with colleagues, friends, and in public spaces).

The author thus calls for more diversity in pragmatic functions of French in textbooks destined for Japanese learners and teachers. She also suggests adding more nuances to role plays in the classroom, in order to help learners communicate efficiently and naturally with French speakers, rather than regurgitating the textbook's information.

Xiaomin M. (2007). Les formules d'excuse et leur enseignement. Synergies Chine, 2, 173-179. https://www.gerflint.fr/Base/Chine2/meng.pdf

This article compares French and Chinese apology systems to highlight social differences surrounding apologies, which lead to confusion and miscommunication for Chinese learners of French. The frequency and type of employment of apologies differ between French and Chinese, which, in addition to causing misunderstandings, can lead to poor impressions of Chinese learners (for example, being a "bad student" or being rude). It is noted that Chinese learners seem to interpret apologies in reference to their own apology system, attempting to translate apologies directly between their L1 and L2.

The author also discusses some of the ways in which pardon is used frequently for small daily faux-pas, like bumping into someone. Xiaomin emphasizes that apologies in French act as reparation for a face-threatening act or offense, but that a lack of response from the recipient of the apology can also be a face-threatening act to the apologizer; thus it is important not only to know how to apologize, but also to know cultural expectations surrounding responses to apologies. This confirms that it is vital to include the Awareness student learning outcomes described in the IPIC model. The article concludes by stating these different systems for apologizing are not sufficiently taught in language classrooms and must be given more attention.