Solidarity in Ichishkíin

Building Solidarity in Ichishkíin

PRACTICAL IDEAS & RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Allyson Alvarado

Union Gap Story - Day and Night | Yakama Legend: Written Version, Spotify

This legend is a story about Union Gap, a geographical landmark that is important to Yakama people for many reasons. The legend is also known as Day and Night because it tells a story of how the animal people created day and night for the humans.

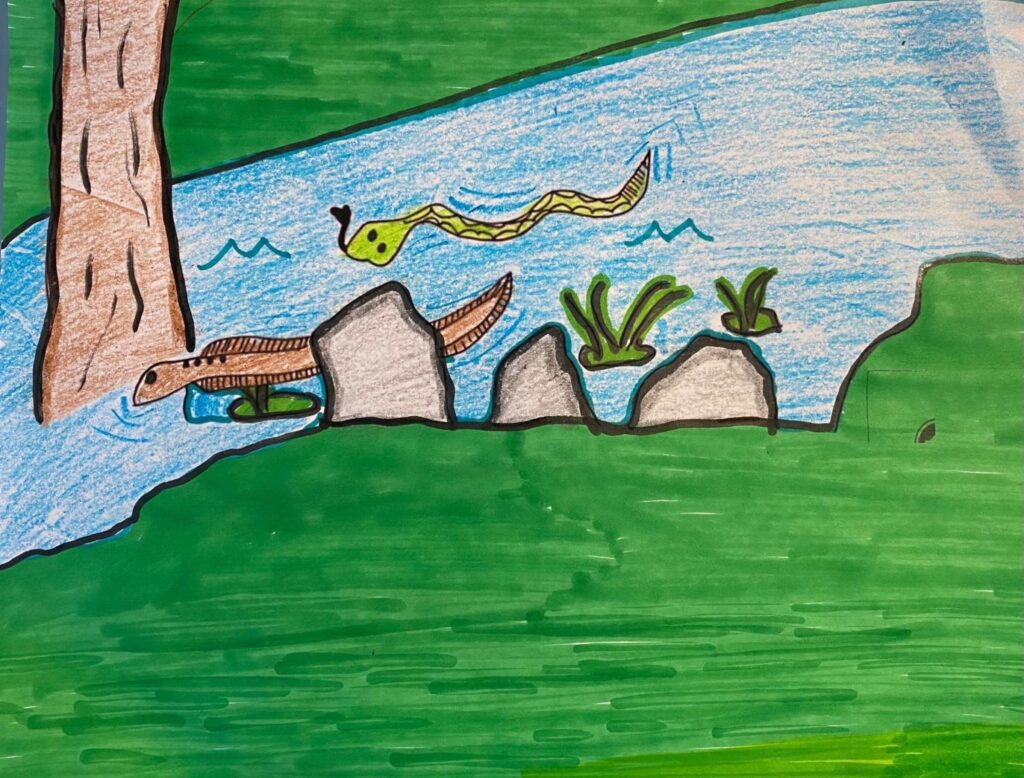

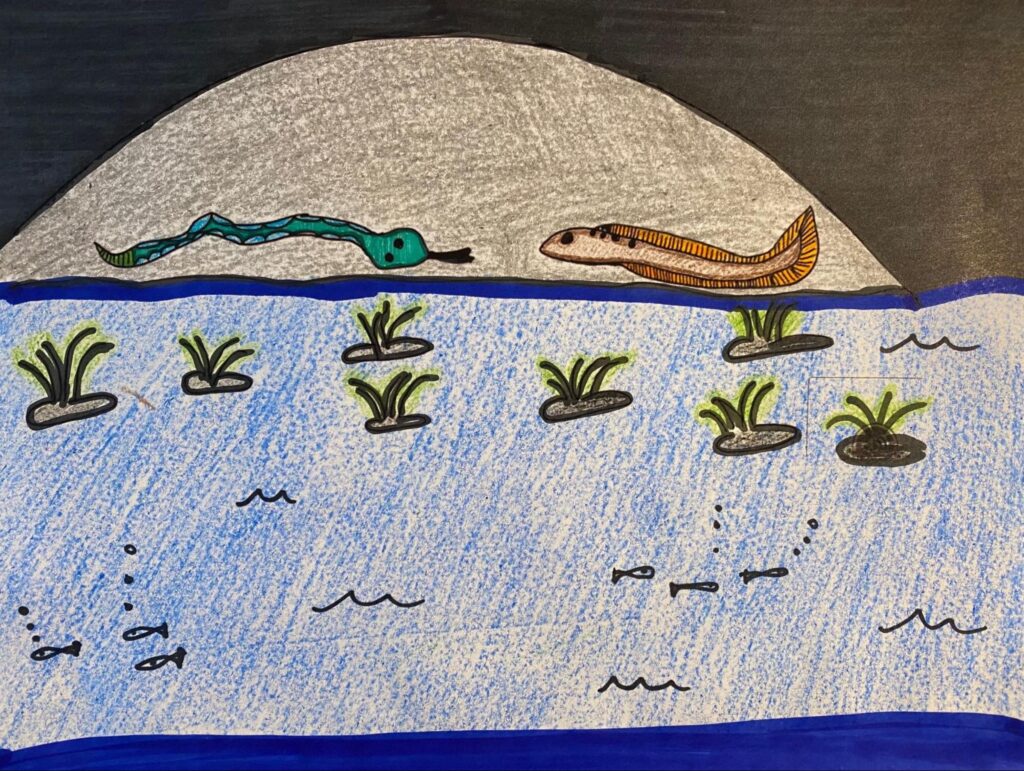

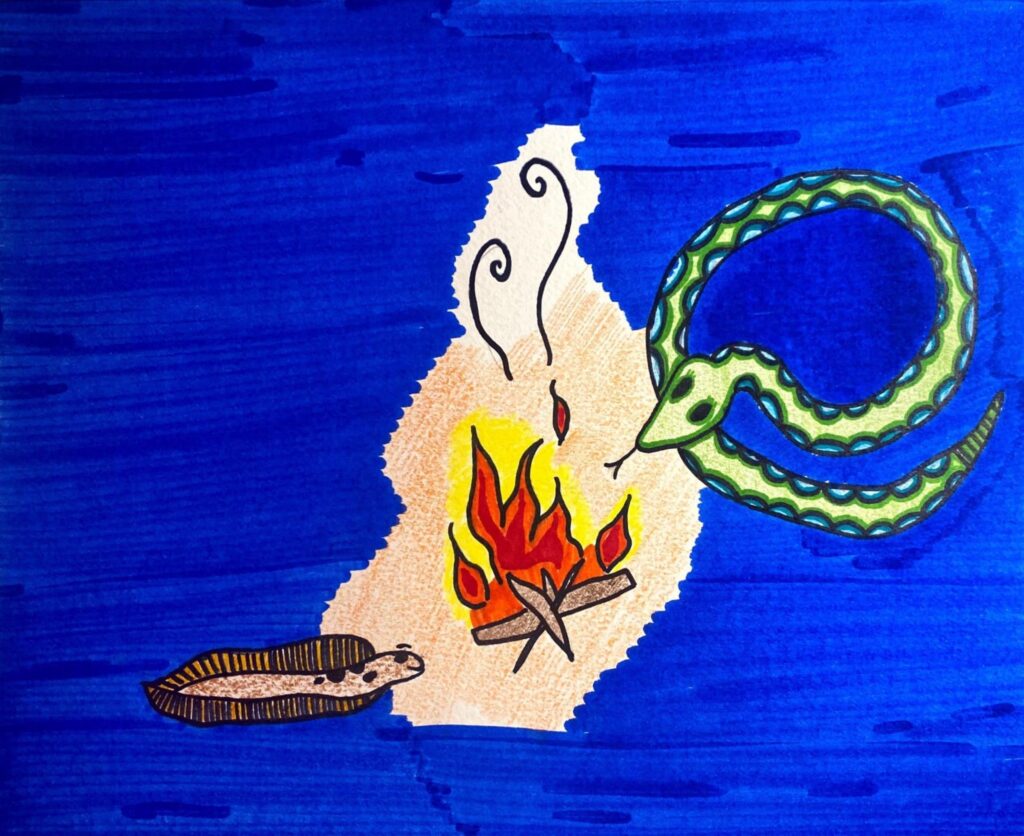

Race Between Rattlesnake and Eel | Yakama Legend: Spotify

Familial Relationships - (1:40-1:55) | Excerpt

At this point in the legend, Eel sees his cousin rattlesnake and says, "Oh, there's my cousin. I better go talk to him. He says, “Oh, cousin, what are you doing up here?” This demonstrates to the listener an example of how you are supposed to act when you see family; it is important to recognize and acknowledge them when you see them. It’s also important to use familial terms as a form of endearment.

(3:10-3:40) | Excerpt

The narrator of the audio version digresses from the story to explain why eels get their "urges" to migrate. She brings up a comparison to fish who do the same thing because of their instinct. Comparing the audio with the written version of the legend makes it clear that those details aren't written in - it simply says that eels wanted to go home.

(7:50-8:10) | Excerpt

In this part of the story, the narrator talks about Rattlesnake and Eel running and racing through hills and creeks. The listener might be confused because an eel lives in water, but the narrator might have started the story by saying that long ago animals could transform into people. In this case, the narrator does not mention this, but others have mentioned it. It is important for listeners to understand and build the relation and connection with these animals.

(8:30-9:00) | Excerpt

Here, the narrator describes a specific landmark called Horsethief Lake. This is a significant place for Yakama people and was mentioned in the story for good reason in relation to the habitats of eels and rattlesnakes.

(9:30) | Excerpt

Throughout the legend, Rattlesnake is cheating Eel by giving him bad directions during their race, making Eel way behind Rattlesnake. At this moment, Eel realizes he is behind. As they are racing by the Columbia River, he can smell it because he can smell his home. He uses all his strength to win and find his way back.

(10:20) | Excerpt

In the end, the Eel won. One of the reasons was that Rattlesnake was too busy teasing Eel during the race, thinking he was going to win. Therefore, Eel got to keep his body and Rattlesnake had to keep his. This is where the narrator starts to explain why the race ended near the Columbia River. She lets the listener know that it is a place where there are many rattlesnake dens, and where eels spawn.

(11:55) | Excerpt

The narrator starts explaining some morals of the story. It is common for narrators not to explain the moral of the story and instead let the children think about what it might be, but sometimes they take the time to explain it. Here, the narrator explains that while you're ahead, be careful about the way you conduct yourself and don't get too confident and don’t tease others. Also, do not cheat people like Rattlesnake did - he ended up not getting what he intended. This teaches children how they should act in the community.

Brown vs. Green Rattlesnakes | Cultural Knowledge

While the narrator does not say this in this audio version or the written version, other times narrators have explained why we only see green rattlesnakes in the mountains. Based on the story, the brown rattlesnakes have to stay down in that area by the Columbia, while the good-looking green Rattlesnakes get to enjoy being in the mountains because they did not lie or cheat or treat their cousin/friend Eel badly.

Landmark relevance in Race Between Rattlesnake and Eel | Cultural Knowledge

This image is a written explanation of the landmarks mentioned in the end of the recording and their relevance to Yakama ways.

Sɨkni (Wild Spring Flowers/Yellowbell) | Yakama Legend: Written Version, Spotify

(0:00-0:30) | Excerpt

At the beginning of the audio recording, the narrator takes the time to explain that a long time ago plants were people. This is not included in the first few lines of the written version. This reflects teaching traditions specific to Yakama beliefs. It shows the reader how the plants were once beings and how we still view them that way today.

(1:00) | Excerpt

The narrator explains how the three sisters (wildflowers) were asleep for the winter. This would be common knowledge for Yakama people because we gather the roots of these flowers to eat. This is a good spot for the narrator to explain to children that we do not gather the flowers during this time because they are sleeping.

(1:20) | Excerpt

At this time, the narrator explains how the Warm Wind blew in and melted all the snow away. This means it was spring time and time for the roots to wake up. This lets the listener know that the time for their family to gather roots is nearing.

(1:55) | Excerpt

In many legends, it is common for the characters to be related in some way and here the Warm Wind is seen as the wild flowers' big brother. In this section, the Warm Wind addresses them as "little sisters". This shows listeners how they should be using these familial terms to address their relatives.

(2:30) | Excerpt

While all of her sisters were getting ready, Sikni was lazing around and not listening to her sisters when they were telling her to get up and get ready for the people. She finally got ready at the last minute, looking "disheveled". She was way behind her sisters. She felt ashamed and hid herself from everyone, bowing her head. When spring time arrives, we can see how the yellowbell plant is the last to bloom, with the flower hanging down. This would be explained to the listener in Yakama storytelling, and it is something they would actually see at springtime.

(5:50) | Excerpt

The narrator explains the general lesson to children: when they are asked to get up in the morning, they should not wait around and not listen, like Sikni. Instead, they should jump up and look at the sun!

(5:50) | Excerpt

The narrator stops to share more cultural background information about how we prepare ourselves in the morning: the traditional way is different from how we get ready nowadays. It is important for young listeners today to understand the sociocultural differences that are evident within the Yakama community and how they have changed since Westernized European influence.

Humor in Ichishkíin

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Johanna Lyon, Cathy Lee, Tung Tuaynak, Jermayne Tuckta, and Ken Ezaki Ronquillo

Looking Back at the 2017 Mother Language Meme Challenge | Blog Post

At the International Mother Language Day, there was an internet challenge to create memes in the mother languages of people from across the globe. The importance of the project was the participation of endangered, minority, heritage languages. It is important for our project, because it demonstrates how humor is different across a multitude of languages. This can be used to show the other memes that were created in the different languages, and students can create their own for a class assignment.

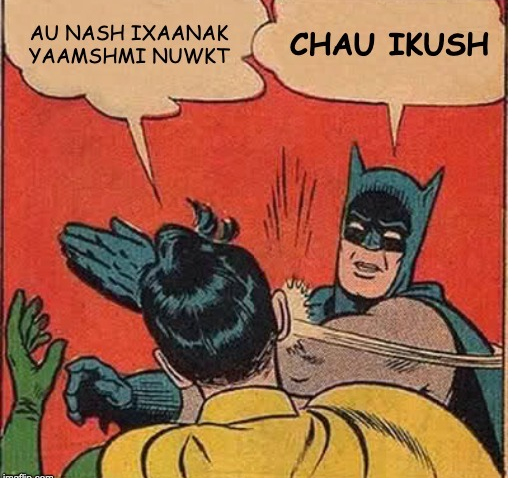

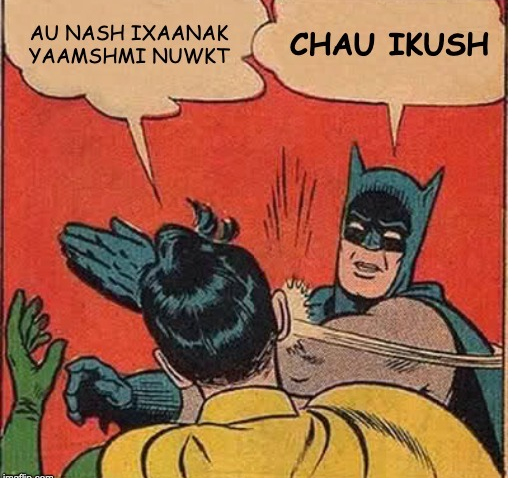

DON’T DO THAT!! | Meme

Translation by Jermayne Tuckta:

Now I will wash all of the deer meat

DON’T DO THAT!!

Joke: In hunting any wild game, in order to preserve all the natural flavors of the meat, one does not wash the meat after butchering it, as the flavors will be lost, and it will have no unique taste.

Bologna Animal | Meme

“My mother taught “our people always hunt for our meat”

Now I wonder “where does the bologna animal live? Maybe my dad knows”’

The Joke: Indigenous peoples were placed onto Reservations where their hunting rights were affected by personal land owners of the traditional hunting grounds. The economy isn’t great, so Bologna is within affordances to big families with multiple generation households, versus going out to hunt for deer/elk/bear/buffalo meat. Since dad always brings bologna home, he must know where the Bologna animal lives, since he hunts it.

Told by a Fluent Speaker of the Umatilla Dialect | Joke

Awkú míimi, ínaš wínana wíyat kwníin tičámpa waníči Florida, ašku naš áyikšanaaš iwá náxš táwn, iwaníša Umatilla,Florida. Ín ku nàpt xátwayma čnamáankni, pínča pa wínana kwná kwáy táwnpa. Awkú na tk'xšana šapášukwat ana mayní iwá či táwn waníči Umatilla? Aškunaš pxwíin, páyš na á'šapnita šíman čúutpamapa, kúma pa šúkwataxna. Awkú mítawma na ášankika kwáana ćuutpamá. Awkú mún na čáxalpiya pćíš wí'aštaš kway čuutpamápa, awkú naxš čmáakli awínš i'wáa'anamš "Níix Páčway".. Á'na, míšatya, mayní čí čmáakli išukša namí sínwitna? Awkú mayk kítu ipátukaya mítat čúut namíyaw, páyu q'wałáni,.. awkú naš ášapniya kway ćmáakli awínš, mayní nam áw šúkwaśa íćiškiin? Ku i'áwunaaš "Íntanat"..... Internet.. Kwáyšwa inmí masawít tamnanáxt

Translation by Jermayne Tuckta:

And so awhile ago, i went way over to that land called Florida. So I was hearing there was one town, it is called Umatilla Florida. I and two friends went from here, and again we went to there that town. And so we wanted to know what it was like, this town called Umatilla. And so I thought, maybe we ask someone about a bar, they should know. Then above we soon asked about there being a bar.. Then when we opened the door there was the bar. And then one African American man he said to me “Good Afternoon”.. Holy, WTF, how this African American man knows our language? And so very fast he did three drinks with us, very happy… and so I asked that African American man, how do you know Ichishkin? And he replied “Internet”... That is my funny story.

Joke: Anything can be learned on the Internet

Told by a fluent speaker in Warm Springs dialect | Joke

Aswan: Kała, tai ttush nami tananma pawalptaikxa xwiyachpa?

Kała: Achaku iwa shukwat miimikni

Aswan: Nami antanama pawalptaikxana xwiyachpa?

Kała: Chau pawalptaikxana xwiyachpa, anałkw’i pawa laxs shukwinch isapsikw’ana walptaiktash xwiyachpa

Aswan: Ahhhna, kush shin iwanishana?

Kała: Iwanishana Shapq'itpama, payu pashwini iwa kush isapsikw'ana tł'aawxmaman namiki

Translation by Jermayne Tuckta:

Boy: Grandma, why do some of our people sing in the sweathouse?

Grandma: Because it's a lesson from long ago

Boy: Our ancestors, they used to sing all the time in the sweathouse?

Grandma: No they didn't always sing in the sweathouse, some day there was one very wise person, he taught how to sing in the sweathouse.

Boy: Ohh, and what was he called?

Kala: His name was TV, very wise he was and he taught everyone about us.

Joke: After moving on to the reservations, the actions of the Indigenous communities were always being watched by the government, and they taught how to live on the reservation, and made their way into other activities, such as the sweathouse, which isn't a spiritual activity for tribes of the Columbia Plateau, like it is for other tribes (such as the tribes from the Plains), where all Indigenous cultures are seen as the same in Hollywood, hence, Indigenous people learning how to be Indigenous from TV.

Told by an Elder in the Warm Springs Dialect | Joke

Laxs anwicht, itaxanana payu k’st tł’aawx tichampa. Kush nami tananma pashapniya Miyuuxna “Mish iwata payu k’ps anm chi anwicht?” Kush pa’na miyuuxna; “chau ash shukwasha, paish ash wina shapnit nami antananma, inash tuxta c’aatpa!” Kush iwinashaiksh. Kush ituxn kaatnamyau kush pa’na; “ii itaxanta payu k’ps anmpa, au na pauwiyakuta xlakt ilkwsh!” Mtaatłk’wipa, anch’a pashapnishiaksh miyuuxna; “iwa k’st anch’axi chikuuk, mish iwata shaax chi anmpa?” kush pa’na miyuuxna; “chau ash shukwasha, paish ash wina shapnit nami antananma, inash tuxta c’aatpa!”kush iwinashaiksh. Auku ituxn kaatnamyau kush pa’na; “ii itaxanta payu k’ps anmpa, au na pauwiyakuta xlakt ilkwsh!” Pinaptłkw’ipa, tł’aawxshin anch’a pashapniya miyuuxna; “Chikuuk iwa k’psxau, mish iwata shaax chi anmpa?” kush anch’a pa’na; “Chau ash shukwasha, paish ash wina shapnit nami antananma, inash tuxta c’aatpa!” kush iwinashaiksh. Kush iwina k’staasyau, iyanawi maik ksks taunpa, kush ishapniya laxs taimuła “mish iwata shaax chi anmpa?” kush pa’na taimuła; “ii inash pxwi payu shaax iwata chi anmpa!” kush miyuux ishapniya; “Mishliki nam shukwa itaxanata shaax chi anmpa?” kush pa’na taimuła: “Achaku tł’aawx natitite paskauwisha xlakt ilkwsh, IWATA PAYU SHAAX CHI ANMPA!”

Translated by Jermayne Tuckta:

One year, it became very cold all over the land. And our people, they asked the chief "Is it going to be a really cold winter this year?" and he told them, the chief; "I don't know, maybe i go and ask our ancestor spirits, i will return soon!" And so he left. Then he returned to the longhouse and he told them; "yes, it will become very cold in winter, now lets gather plenty of wood!" Three days passed, and again they asked the chief; : "Again, it is very cold today, is it going to be bad this winter?" and so he told them, the chief; "I don't know, maybe i go and ask our ancestor spirits, i will return soon!" and so he went. And then he returned to the longhouse and he told them; "yes i will become very cold in winter, now lets gather plenty of wood!" Four days pass, everyone again asked the chief; "Today is the coldest, is it going to be bad this winter?" and again he told them; "I don't know, maybe i go to ask our ancestor spirits, i will return soon!" And so he went. And then he went towards the north, he arrived to a small little town, and he asked one news reporter; "Is it going to be bad this winter?" and he told him, the news reporter; " yes i think it's going to be bad this winter!" and so the chief he asked; "how do you know it will become bad this winter?" and so he told him, the news reporter; "because all the Indians are gathering plenty of wood. SO IT WILL BE VERY BAD THIS WINTER!"

Joke: The chief is trying to save face as a person who still carries "old tricks," but rather than asking the spirits, he asks the news reporter in the small town to the north. However, the news reporter doesn't know and is judging the year based off the Indigenous peoples gathering of wood, which the "spirits" are telling them that it'll be a bad winter

Academic Resources on Building Solidarity in Ichishkíin

Resources in this section curated by: Allyson Alvarado

Bird, L. R. (2017). Reflections on revitalizing and reinforcing native languages and cultures. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2017.1371821

Lanny Real Bird's essay demonstrates how nativist expressions, historic practices, and perceptions can contribute to language revitalization and understanding between communities. The author also discusses the importance for Native educators to be able to integrate traditional knowledge and practices into their teaching pedagogy to enforce and encourage the presence of language, culture, and history. The essay is relevant to building solidarity and understanding in the classroom through a traditional practice such as storytelling.

Datta, R. (2017). Traditional storytelling: An effective indigenous research methodology and its implications for environmental research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117741351

Ranjan Datta uses two case studies to explain what storytelling can do for research participants and researchers. One section of the article specifically discusses how traditional storytelling can contribute to Indigenous research and also how this can build upon critical relationships with Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-holders. While this article is not directly related to second language acquisition research, such case studies demonstrate how the practice of traditional storytelling can build upon relationships and encourage solidarity in many areas between different people. In a public school language classroom, for example, relationships can be built between the tribe's Knowledge-holders and the school district/students by bringing an Elder in to share a story.

Doerfler, J., Sinclair, N. J., Stark, H. K., Garroutte, E. M., & Westcott, K. D. (2013). The Story is a Living Being: Companionship with Stories in Anishinaabeg Studies. In Centering Anishinaabeg Studies: Understanding the world through stories (pp. 61–79). Essay, Michigan State University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290950729_The_story_is_a_living_being_Companionship_with_stories_in_Anishinaabeg_studies

Garroutte and Westcott delve into how stories are used within Anishinaabeg studies. Stories are about more than just "finding themes" - they are about informing human life. Using an Anishinaabe legend, the authors show the ways in which people can engage more intensely with stories. They also claim that stories can have an effect on realities and lives. This is relevant to building solidarity and understanding in language learning because it shows the greater impact stories can have on learners outside of language learning: stories affect us as people and how we interact with others and the world around us.

Frantz, K. K. (2021). Language learning in repeated storytellings. Storytelling in Multilingual Interaction, 204–224. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429029240-13

This article uses conversation analysis to observe how learners are able to make repairs in their language use during storytelling. Frantz shows how this not only contributed to phonological and grammatical repairs being made, but also sociocultural repairs. Moreover, there was evident change in participants' multiple interactions with other peers and teachers. This article demonstrates how by using storytelling, learners can build a better understanding of the language in order to build relationships with others in the community.

Gutierrez Arvizu, M. N. (2020). L2 vocabulary acquisition through narratives in an EFL public elementary school. IAFOR Journal of Education, 8(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.8.1.07

Maria Nelly Guitierrez Arvizu explains the use of narratives within language teaching. The natural context of narratives provides language input, leading to an effective way to teach vocabulary. The author investigated the effectiveness of using stories and pre-teaching vocabulary in an elementary school. Results showed that there was improvement in vocabulary development overall, which then led to students being better able to communicate. By incorporating storytelling into the classroom, learners can build a positive language learning relationship and be able to communicate better with their community.

Henne-Ochoa, R. (2018). Sustaining and revitalizing traditional indigenous ways of speaking: An ethnography-of-speaking approach. Language & Communication, 62, 66–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2018.07.002

The author of this article explains the importance of including traditional ways of speaking when maintaining and revitalizing a language. Often, within language revitalization programs, Indigenous ways of teaching and learning are overlooked and overshadowed by euro-westernized ways of teaching. The author uses speech from Lakota people to give the reader insight into how using Indigenous traditional ways as an approach to language learning can better sustain and revitalize languages. When thinking about building solidarity and understanding within language communities, this article speaks to how using Indigenous traditional storytelling would be the way to encourage this in comparison to westernized ways of teaching and learning.

Jansen, J. W. (2010). A grammar of Yakima Ichishkíin/Sahaptin (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon). http://hdl.handle.net/1794/10901

In this grammar of one of the Ichishkiin dialects, Joana Jansen discusses the importance of using storytelling in Indigenous communities and what they mean to Plateau society. Jansen further explains how this relates to teaching language. She uses findings from other researchers to show what storytelling can do for language classrooms and provides examples of ways in which legends have supported language learning, such as in an Ichishkiin classroom.

One particular point that was made by a Warmsprings tribal member named George Aguilar is that storytelling is used to explain important geographical areas. Explaining geographical areas through storytelling is one way Ichishkiin speakers could educate children. It would contribute to their understanding of not only the areas, but the language that goes with it. This in turn could aid in building relationships intergenerationally and with the land.

Kahakalau, K. (2017). Developing an Indigenous proficiency scale. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2017.1377508

The author of this article discusses the development of an assessment tool within a Hawaiian language program and how it was created with the purpose of supporting their learners, instructors and researchers. It also reflected their own culture and language identities, moving away from westernized ways of testing/proficiency. Specifically, Kahakalau mentions how metaphors in their language reflect who they are. Therefore, it was necessary to include them in the assessment tool. Kahakalau emphasizes how the assessment was not only assessing learners’ linguistic abilities, but also how the learners were engaging in native culture and traditions through language. Therefore, it is important to integrate Indigenous ways of storytelling into the classroom; they are deeply rooted into many tribal ways of teaching/learning and could facilitate understanding of the linguistics and pragmatics of a language.

Martinez, D. E. (2021.) Storying traditions, lessons and lives: Responsible and grounded indigenous storying ethics and methods. Genealogy 5(84). https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040084

Doreen Martinez writes about Indigenous storytelling and its distinctive ethics, methods, elements, premises, and practices. She uses storytelling experiences and data to show how these are grounded in Indigenous truths and epistemologies that empower storytelling which comes from ancient and traditional practices. Specifically, Martinez discusses the relationship among storytellers, the relationship between storytellers and the listeners, and how it looked over time. This is relevant to building solidarity between these members and how these relationships are seen intergenerationally within Indigenous storytelling.

McCarty, T. L., Nicholas, S. E., Chew, K. A., Diaz, N. G., Leonard, W. Y., & White, L. (2018). Hear our languages, hear our voices: Storywork as theory and praxis in indigenous-language reclamation. Daedalus, 147(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_00499

In this article, the authors explain how narratives are used in Indigenous language reclamation. The authors make clear that there is more than just language in language reclamation; personal and communal agency, identity, and belonging are a part of it as well. A major point they make is the importance of centering Indigenous experiences, which speaks to building solidarity within a language community through storytelling. In the classroom setting, in addition to learning vocabulary, learners can delve into the deeper meaning of the story and the experiences of the narrator/characters.

Minthorn, R. S., Shotton, H. J., & Tachine, A. R. (2018). Story rug: Weaving stories into research. In Reclaiming indigenous research in higher education (pp. 64–75). Essay, Rutgers University Press. https://ww1.odu.edu/content/dam/odu/col-dept/education/docs/reclaiming-indigenous-research-in-higher-education.pdf

The author of this chapter discusses how storytelling is essential for learning and positively transforming Indigenous communities. One of the main points made by Tachine is that stories unite and allow people to learn from each other. Stories are a "vessel" to pass along teaching and practices to members. This furthers the idea and importance of building solidarity and understanding between different generations or across communities.

Peltier, S. (2017). An Anishinaabe perspective on children’s language learning to inform “seeing the Aboriginal child.” Language and Literacy, 19(2), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.20360/g2n95c

In this article, Sharla Peltier addresses the effects of Western-European epistemologies on Aboriginal children within the home and school. The author also examines how various Indigenous pedagogy educational approaches engage learners. Specifically, Anishinaabe oral traditions and ways of teaching are listener-inclusive - they encourage listening, thinking, reflecting, experiencing, and engaging, in comparison to a westernized-center form of learning where the teacher often has all the authority. This way of teaching builds solidarity between the teacher and the learner and balances the power dynamics so that learners are better able to participate and learn.

Schonleber, N. (2021). Using the cosmic curriculum of Dr. Montessori toward the development of a place-based Indigenous Science Program. Journal of Montessori Research, 7(2), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v7i2.15763

Nanette Schonleber conducted a three-year qualitative case study to explore the use of culturally restorative and decolonized pedagogies by Indigenous educators that can be used to teach sciences. The author reviewed how this worked in a Hawaiian language immersion program. She specifically looked at how the use of storytelling contributed to students' learning. When teachers used a "Montessori" approach, which combines cultural values such as storytelling while still accounting for state-mandated science evaluations, they felt it was productive. This is an example of how solidarity and understanding can be built between these two elements. While not particularly focused on second language acquisition, the article shows how storytelling and similar practices can work in a language classroom towards other important cultural ideas that contribute to how that community relates to each other and the land.

Siragusa, L., & Virtanen, P. K. (2021). The materiality of languages in engagements with the environment. Multilingua, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2021-0057

This author explains the relationship between language materiality with "other-than human actors” and their presence to show how this contributes to an increase in certain aspects of language. The most important finding in this study is that the use of social practices and embodied skills shows evidence of language materiality. Narrative traditions used with language technology can contribute to the forming of very meaningful relationships within communities. Using storytelling is important in second language acquisition because it builds stronger and deeper relationships between the narrator/listener and "other-than human actors" in the narratives that are important to that community.

Verbos, A. K., & Humphries, M. (2013). A Native American relational ethic: An indigenous perspective on teaching human responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1790-3

Anne Verbos and Maria Humphries discuss how learners can reflect on values and lessons within Indigenous communities through Indigenous stories. They explain how these values and lessons are related to ethics, leadership, teamwork, and relationships. An important idea is that, although involving storytelling into these spaces is valuable and brings a different perspective, respect for the people and communities doing the sharing is just as important. This is very crucial to building relationships and solidarity within communities and with people outside the community who want to work with the language.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON HUMOR IN Ichishkíin

Resources in this section curated by: Johanna Lyon, Cathy Lee, Tung Tuaynak, Jermayne Tuckta, and Ken Ezaki Ronquillo

Fairbanks, B (2016). Ojibwe Discourse Markers. Lincoln, Nebraska. London England. University of Nebraska Press.

In this article, Brendand Fairbanks spends much time studying the Ojibwe language, and how some markers are used for specific purposes. Overall, words exist in Ojibwe to draw the listeners attention to something specific, for example; inashke literally translates into “look,” however in Ojibwe, it doesn’t not mean to literally look at something, but more to draw your attention to something specific, i.e. Nashke Bizindan, which translates into “Look Listen,” meaning; pay attention to my command of “LISTEN.” Throughout his studies, as he dives into stories with fluent speakers, this term transpires again to provide examples (paying close attention to the example, as it is the main key concept of the story), and it also is used as a tool to reflect the speaker's actions in some cases. Another marker is used in the same way which is Mii, where there is no exact direct English translation. The examples used with this marker tends to point out a transition or explanation (i.g. and so, that’s why, and now). This allows a transition from the example back into the main topic at hand.

In Indigenous cases, such as mine in Ichishkiin, these markers often come up in conversation humor amongst the community which are perlocutionary markers for the listener to comprehend the joke.

Moore, David. (2014). That Dream Shall Have a Name: Native Americans Rewriting America. The Last Laugh: Humour and Humanity in Native American Pluralism. 300-364.

Moore describes humor as human grounded, where Indigenous humor is grounded in a “more-than-human world. Within the Indigenous humor context, Indigenous members generally have two different humor concepts; one which is described as an inner group tease in which a member within an Indigenous group can leave their comfort zone of their identity and ego to identify with the group that is “teasing.” The outer teasing refers to others that don’t identify with Indigenous peoples that have the ability to identify the reality of Indigenous history and historical humility (i.g. can they become comfortable with the idea of Europeans genocide on the Indigenous population, which has been accepted by most Indigenous communities). In this article, Moore introduces four Indigenous scholars that directs Indigenous humor in different ways to the Indigenous communities (where they shed their own identity to fit in with Indigenous communities throughout the North American Continent); Apess has a focus on ironies of American Christian hypocrisy against Indigenous peoples, Vine Deloria Jr focuses American legal history against Indigenous sovereignty, and Vizenor that focuses on language used in American Ideology against Indigenous realities. The fourth is a writer; Sherman Alexi, who directs his humor back towards sovereignty, meaning; you can only be “Indian” today by sovereign rights granted by the government. Through Indigenous languages, the natural humor has changed from jokes that may have been seen as “innocent” in earlier times, but due to the socio-political factors at play within the Indigenous communities, much of politics, identity, and sarcasm has become part of humor within the Indigenous languages.

Moore, David. (2014). That Dream Shall Have a Name: Native Americans Rewriting America. The Last Laugh: Humour and Humanity in Native American Pluralism. 300-364.

Moore describes humor as human grounded, where Indigenous humor is grounded in a “more-than-human world. Within the Indigenous humor context, Indigenous members generally have two different humor concepts; one which is described as an inner group tease in which a member within an Indigenous group can leave their comfort zone of their identity and ego to identify with the group that is “teasing.” The outer teasing refers to others that don’t identify with Indigenous peoples that have the ability to identify the reality of Indigenous history and historical humility (i.g. can they become comfortable with the idea of Europeans genocide on the Indigenous population, which has been accepted by most Indigenous communities). In this article, Moore introduces four Indigenous scholars that directs Indigenous humor in different ways to the Indigenous communities (where they shed their own identity to fit in with Indigenous communities throughout the North American Continent); Apess has a focus on ironies of American Christian hypocrisy against Indigenous peoples, Vine Deloria Jr focuses American legal history against Indigenous sovereignty, and Vizenor that focuses on language used in American Ideology against Indigenous realities. The fourth is a writer; Sherman Alexi, who directs his humor back towards sovereignty, meaning; you can only be “Indian” today by sovereign rights granted by the government. Through Indigenous languages, the natural humor has changed from jokes that may have been seen as “innocent” in earlier times, but due to the socio-political factors at play within the Indigenous communities, much of politics, identity, and sarcasm has become part of humor within the Indigenous languages.

Sinkeviciute, V., & Dynel, M. (2017). Approaching conversational humour culturally: A survey of the emerging area of investigation. Language and Communication, 55, 1-9.

Humor that transpires through technology and social media stems from humor theories based from classic philosophy and uses the same mechanisms and characteristics throughout different cultures and languages. Jokes can be broken down into two different forms, one being a “canned joke” which includes memes, comic strips, or any other joke that has no interaction between the speaker and listener. Conversation humors stem from the verbal behaviors in an interaction between two or more people. Teasing a friend is seen as bonding in a friendly manner and sometimes seen as a solidarity-building function. From this comes Disaffiliative humor which consists of targeting someone specific within an interaction that includes sarcasm for the purpose of the speaker reaping the humorous rewards within the interaction. One other form of conversation humor is banter, which is also referred to as” joint fantasizing” which is an offensive way of being friendly, as the speaker and listener find common ground in terms of language usage. On an intracultural level, conversational humor, in most cases, transpires amongst families, peers, and close communities. Some exceptions include Australia and New Zealand, where conversation humor is used to create a bond between strangers.

In the Americas, teasing amongst strangers calls for a “stronger need for identity display,” meaning; peers and family tend to get an understanding of where one might be standing within their own identity and or where they stand on some opinions.