Community events in Ichishkíin

Building Solidarity in Ichishkíin

PRACTICAL IDEAS & RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Allyson Alvarado

Union Gap Story - Day and Night | Yakama Legend: Written Version, Spotify

This legend is a story about Union Gap, a geographical landmark that is important to Yakama people for many reasons. The legend is also known as Day and Night because it tells a story of how the animal people created day and night for the humans.

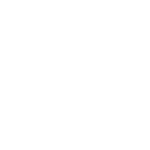

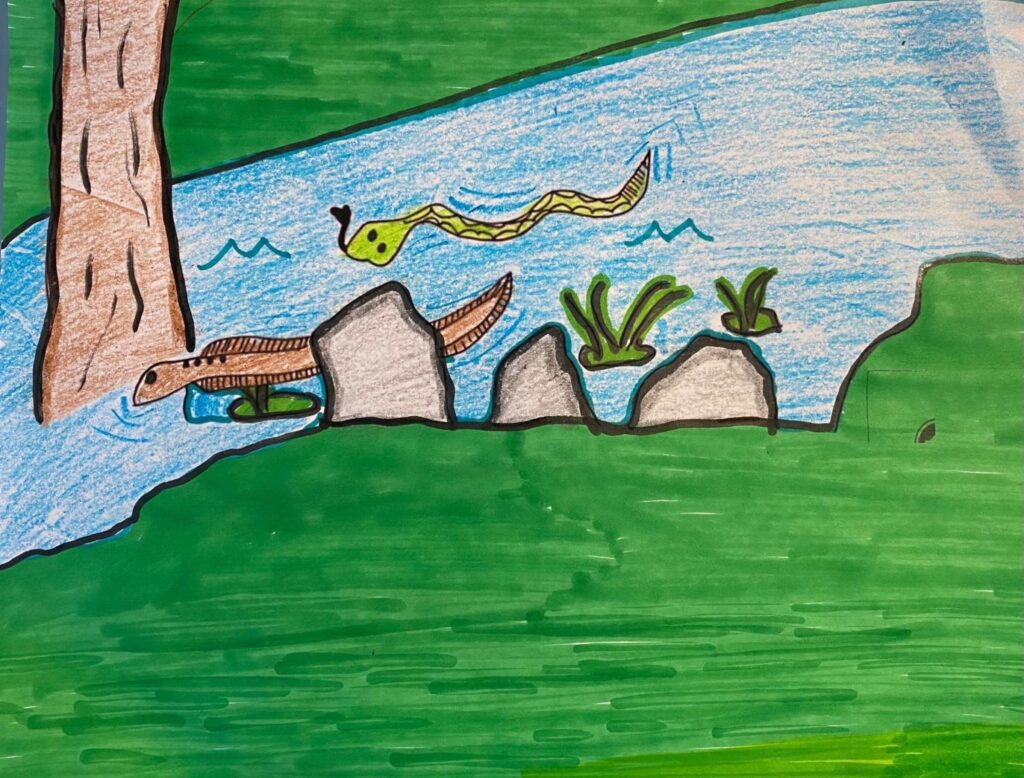

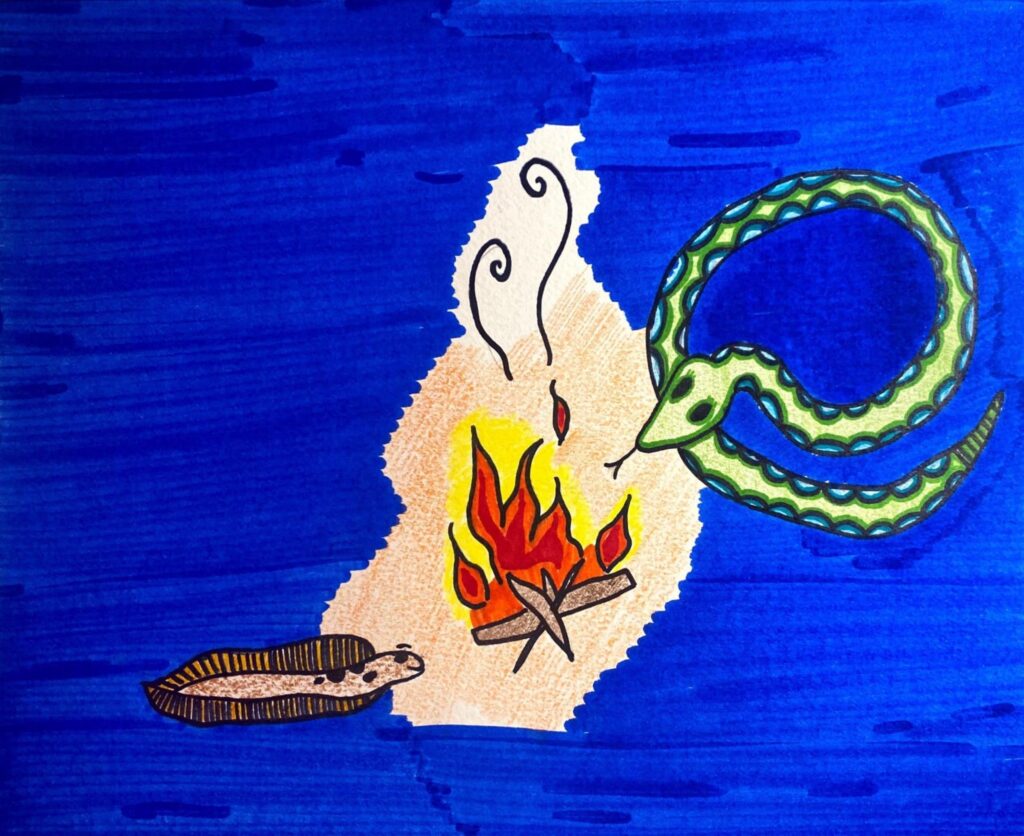

Race Between Rattlesnake and Eel | Yakama Legend: Spotify

Familial Relationships - (1:40-1:55) | Excerpt

At this point in the legend, Eel sees his cousin rattlesnake and says, "Oh, there's my cousin. I better go talk to him. He says, “Oh, cousin, what are you doing up here?” This demonstrates to the listener an example of how you are supposed to act when you see family; it is important to recognize and acknowledge them when you see them. It’s also important to use familial terms as a form of endearment.

(3:10-3:40) | Excerpt

The narrator of the audio version digresses from the story to explain why eels get their "urges" to migrate. She brings up a comparison to fish who do the same thing because of their instinct. Comparing the audio with the written version of the legend makes it clear that those details aren't written in - it simply says that eels wanted to go home.

(7:50-8:10) | Excerpt

In this part of the story, the narrator talks about Rattlesnake and Eel running and racing through hills and creeks. The listener might be confused because an eel lives in water, but the narrator might have started the story by saying that long ago animals could transform into people. In this case, the narrator does not mention this, but others have mentioned it. It is important for listeners to understand and build the relation and connection with these animals.

(8:30-9:00) | Excerpt

Here, the narrator describes a specific landmark called Horsethief Lake. This is a significant place for Yakama people and was mentioned in the story for good reason in relation to the habitats of eels and rattlesnakes.

(9:30) | Excerpt

Throughout the legend, Rattlesnake is cheating Eel by giving him bad directions during their race, making Eel way behind Rattlesnake. At this moment, Eel realizes he is behind. As they are racing by the Columbia River, he can smell it because he can smell his home. He uses all his strength to win and find his way back.

(10:20) | Excerpt

In the end, the Eel won. One of the reasons was that Rattlesnake was too busy teasing Eel during the race, thinking he was going to win. Therefore, Eel got to keep his body and Rattlesnake had to keep his. This is where the narrator starts to explain why the race ended near the Columbia River. She lets the listener know that it is a place where there are many rattlesnake dens, and where eels spawn.

(11:55) | Excerpt

The narrator starts explaining some morals of the story. It is common for narrators not to explain the moral of the story and instead let the children think about what it might be, but sometimes they take the time to explain it. Here, the narrator explains that while you're ahead, be careful about the way you conduct yourself and don't get too confident and don’t tease others. Also, do not cheat people like Rattlesnake did - he ended up not getting what he intended. This teaches children how they should act in the community.

Brown vs. Green Rattlesnakes | Cultural Knowledge

While the narrator does not say this in this audio version or the written version, other times narrators have explained why we only see green rattlesnakes in the mountains. Based on the story, the brown rattlesnakes have to stay down in that area by the Columbia, while the good-looking green Rattlesnakes get to enjoy being in the mountains because they did not lie or cheat or treat their cousin/friend Eel badly.

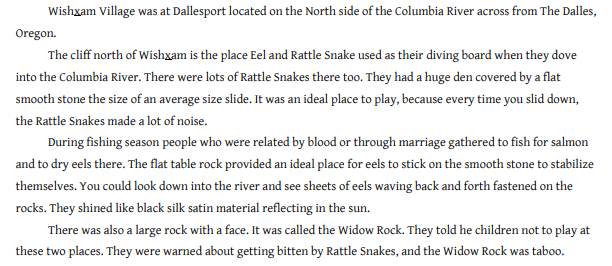

Landmark relevance in Race Between Rattlesnake and Eel | Cultural Knowledge

This image is a written explanation of the landmarks mentioned in the end of the recording and their relevance to Yakama ways.

Sɨkni (Wild Spring Flowers/Yellowbell) | Yakama Legend: Written Version, Spotify

(0:00-0:30) | Excerpt

At the beginning of the audio recording, the narrator takes the time to explain that a long time ago plants were people. This is not included in the first few lines of the written version. This reflects teaching traditions specific to Yakama beliefs. It shows the reader how the plants were once beings and how we still view them that way today.

(1:00) | Excerpt

The narrator explains how the three sisters (wildflowers) were asleep for the winter. This would be common knowledge for Yakama people because we gather the roots of these flowers to eat. This is a good spot for the narrator to explain to children that we do not gather the flowers during this time because they are sleeping.

(1:20) | Excerpt

At this time, the narrator explains how the Warm Wind blew in and melted all the snow away. This means it was spring time and time for the roots to wake up. This lets the listener know that the time for their family to gather roots is nearing.

(1:55) | Excerpt

In many legends, it is common for the characters to be related in some way and here the Warm Wind is seen as the wild flowers' big brother. In this section, the Warm Wind addresses them as "little sisters". This shows listeners how they should be using these familial terms to address their relatives.

(2:30) | Excerpt

While all of her sisters were getting ready, Sikni was lazing around and not listening to her sisters when they were telling her to get up and get ready for the people. She finally got ready at the last minute, looking "disheveled". She was way behind her sisters. She felt ashamed and hid herself from everyone, bowing her head. When spring time arrives, we can see how the yellowbell plant is the last to bloom, with the flower hanging down. This would be explained to the listener in Yakama storytelling, and it is something they would actually see at springtime.

(5:50) | Excerpt

The narrator explains the general lesson to children: when they are asked to get up in the morning, they should not wait around and not listen, like Sikni. Instead, they should jump up and look at the sun!

(5:50) | Excerpt

The narrator stops to share more cultural background information about how we prepare ourselves in the morning: the traditional way is different from how we get ready nowadays. It is important for young listeners today to understand the sociocultural differences that are evident within the Yakama community and how they have changed since Westernized European influence.

Academic Resources on Building Solidarity in Ichishkíin

Resources in this section curated by: Allyson Alvarado

Bird, L. R. (2017). Reflections on revitalizing and reinforcing native languages and cultures. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2017.1371821

Lanny Real Bird's essay demonstrates how nativist expressions, historic practices, and perceptions can contribute to language revitalization and understanding between communities. The author also discusses the importance for Native educators to be able to integrate traditional knowledge and practices into their teaching pedagogy to enforce and encourage the presence of language, culture, and history. The essay is relevant to building solidarity and understanding in the classroom through a traditional practice such as storytelling.

Datta, R. (2017). Traditional storytelling: An effective indigenous research methodology and its implications for environmental research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117741351

Ranjan Datta uses two case studies to explain what storytelling can do for research participants and researchers. One section of the article specifically discusses how traditional storytelling can contribute to Indigenous research and also how this can build upon critical relationships with Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-holders. While this article is not directly related to second language acquisition research, such case studies demonstrate how the practice of traditional storytelling can build upon relationships and encourage solidarity in many areas between different people. In a public school language classroom, for example, relationships can be built between the tribe's Knowledge-holders and the school district/students by bringing an Elder in to share a story.

Doerfler, J., Sinclair, N. J., Stark, H. K., Garroutte, E. M., & Westcott, K. D. (2013). The Story is a Living Being: Companionship with Stories in Anishinaabeg Studies. In Centering Anishinaabeg Studies: Understanding the world through stories (pp. 61–79). Essay, Michigan State University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290950729_The_story_is_a_living_being_Companionship_with_stories_in_Anishinaabeg_studies

Garroutte and Westcott delve into how stories are used within Anishinaabeg studies. Stories are about more than just "finding themes" - they are about informing human life. Using an Anishinaabe legend, the authors show the ways in which people can engage more intensely with stories. They also claim that stories can have an effect on realities and lives. This is relevant to building solidarity and understanding in language learning because it shows the greater impact stories can have on learners outside of language learning: stories affect us as people and how we interact with others and the world around us.

Frantz, K. K. (2021). Language learning in repeated storytellings. Storytelling in Multilingual Interaction, 204–224. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429029240-13

This article uses conversation analysis to observe how learners are able to make repairs in their language use during storytelling. Frantz shows how this not only contributed to phonological and grammatical repairs being made, but also sociocultural repairs. Moreover, there was evident change in participants' multiple interactions with other peers and teachers. This article demonstrates how by using storytelling, learners can build a better understanding of the language in order to build relationships with others in the community.

Gutierrez Arvizu, M. N. (2020). L2 vocabulary acquisition through narratives in an EFL public elementary school. IAFOR Journal of Education, 8(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.8.1.07

Maria Nelly Guitierrez Arvizu explains the use of narratives within language teaching. The natural context of narratives provides language input, leading to an effective way to teach vocabulary. The author investigated the effectiveness of using stories and pre-teaching vocabulary in an elementary school. Results showed that there was improvement in vocabulary development overall, which then led to students being better able to communicate. By incorporating storytelling into the classroom, learners can build a positive language learning relationship and be able to communicate better with their community.

Henne-Ochoa, R. (2018). Sustaining and revitalizing traditional indigenous ways of speaking: An ethnography-of-speaking approach. Language & Communication, 62, 66–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2018.07.002

The author of this article explains the importance of including traditional ways of speaking when maintaining and revitalizing a language. Often, within language revitalization programs, Indigenous ways of teaching and learning are overlooked and overshadowed by euro-westernized ways of teaching. The author uses speech from Lakota people to give the reader insight into how using Indigenous traditional ways as an approach to language learning can better sustain and revitalize languages. When thinking about building solidarity and understanding within language communities, this article speaks to how using Indigenous traditional storytelling would be the way to encourage this in comparison to westernized ways of teaching and learning.

Jansen, J. W. (2010). A grammar of Yakima Ichishkíin/Sahaptin (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon). http://hdl.handle.net/1794/10901

In this grammar of one of the Ichishkiin dialects, Joana Jansen discusses the importance of using storytelling in Indigenous communities and what they mean to Plateau society. Jansen further explains how this relates to teaching language. She uses findings from other researchers to show what storytelling can do for language classrooms and provides examples of ways in which legends have supported language learning, such as in an Ichishkiin classroom.

One particular point that was made by a Warmsprings tribal member named George Aguilar is that storytelling is used to explain important geographical areas. Explaining geographical areas through storytelling is one way Ichishkiin speakers could educate children. It would contribute to their understanding of not only the areas, but the language that goes with it. This in turn could aid in building relationships intergenerationally and with the land.

Kahakalau, K. (2017). Developing an Indigenous proficiency scale. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2017.1377508

The author of this article discusses the development of an assessment tool within a Hawaiian language program and how it was created with the purpose of supporting their learners, instructors and researchers. It also reflected their own culture and language identities, moving away from westernized ways of testing/proficiency. Specifically, Kahakalau mentions how metaphors in their language reflect who they are. Therefore, it was necessary to include them in the assessment tool. Kahakalau emphasizes how the assessment was not only assessing learners’ linguistic abilities, but also how the learners were engaging in native culture and traditions through language. Therefore, it is important to integrate Indigenous ways of storytelling into the classroom; they are deeply rooted into many tribal ways of teaching/learning and could facilitate understanding of the linguistics and pragmatics of a language.

Martinez, D. E. (2021.) Storying traditions, lessons and lives: Responsible and grounded indigenous storying ethics and methods. Genealogy 5(84). https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040084

Doreen Martinez writes about Indigenous storytelling and its distinctive ethics, methods, elements, premises, and practices. She uses storytelling experiences and data to show how these are grounded in Indigenous truths and epistemologies that empower storytelling which comes from ancient and traditional practices. Specifically, Martinez discusses the relationship among storytellers, the relationship between storytellers and the listeners, and how it looked over time. This is relevant to building solidarity between these members and how these relationships are seen intergenerationally within Indigenous storytelling.

McCarty, T. L., Nicholas, S. E., Chew, K. A., Diaz, N. G., Leonard, W. Y., & White, L. (2018). Hear our languages, hear our voices: Storywork as theory and praxis in indigenous-language reclamation. Daedalus, 147(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_00499

In this article, the authors explain how narratives are used in Indigenous language reclamation. The authors make clear that there is more than just language in language reclamation; personal and communal agency, identity, and belonging are a part of it as well. A major point they make is the importance of centering Indigenous experiences, which speaks to building solidarity within a language community through storytelling. In the classroom setting, in addition to learning vocabulary, learners can delve into the deeper meaning of the story and the experiences of the narrator/characters.

Minthorn, R. S., Shotton, H. J., & Tachine, A. R. (2018). Story rug: Weaving stories into research. In Reclaiming indigenous research in higher education (pp. 64–75). Essay, Rutgers University Press. https://ww1.odu.edu/content/dam/odu/col-dept/education/docs/reclaiming-indigenous-research-in-higher-education.pdf

The author of this chapter discusses how storytelling is essential for learning and positively transforming Indigenous communities. One of the main points made by Tachine is that stories unite and allow people to learn from each other. Stories are a "vessel" to pass along teaching and practices to members. This furthers the idea and importance of building solidarity and understanding between different generations or across communities.

Peltier, S. (2017). An Anishinaabe perspective on children’s language learning to inform “seeing the Aboriginal child.” Language and Literacy, 19(2), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.20360/g2n95c

In this article, Sharla Peltier addresses the effects of Western-European epistemologies on Aboriginal children within the home and school. The author also examines how various Indigenous pedagogy educational approaches engage learners. Specifically, Anishinaabe oral traditions and ways of teaching are listener-inclusive - they encourage listening, thinking, reflecting, experiencing, and engaging, in comparison to a westernized-center form of learning where the teacher often has all the authority. This way of teaching builds solidarity between the teacher and the learner and balances the power dynamics so that learners are better able to participate and learn.

Schonleber, N. (2021). Using the cosmic curriculum of Dr. Montessori toward the development of a place-based Indigenous Science Program. Journal of Montessori Research, 7(2), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v7i2.15763

Nanette Schonleber conducted a three-year qualitative case study to explore the use of culturally restorative and decolonized pedagogies by Indigenous educators that can be used to teach sciences. The author reviewed how this worked in a Hawaiian language immersion program. She specifically looked at how the use of storytelling contributed to students' learning. When teachers used a "Montessori" approach, which combines cultural values such as storytelling while still accounting for state-mandated science evaluations, they felt it was productive. This is an example of how solidarity and understanding can be built between these two elements. While not particularly focused on second language acquisition, the article shows how storytelling and similar practices can work in a language classroom towards other important cultural ideas that contribute to how that community relates to each other and the land.

Siragusa, L., & Virtanen, P. K. (2021). The materiality of languages in engagements with the environment. Multilingua, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2021-0057

This author explains the relationship between language materiality with "other-than human actors” and their presence to show how this contributes to an increase in certain aspects of language. The most important finding in this study is that the use of social practices and embodied skills shows evidence of language materiality. Narrative traditions used with language technology can contribute to the forming of very meaningful relationships within communities. Using storytelling is important in second language acquisition because it builds stronger and deeper relationships between the narrator/listener and "other-than human actors" in the narratives that are important to that community.

Verbos, A. K., & Humphries, M. (2013). A Native American relational ethic: An indigenous perspective on teaching human responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1790-3

Anne Verbos and Maria Humphries discuss how learners can reflect on values and lessons within Indigenous communities through Indigenous stories. They explain how these values and lessons are related to ethics, leadership, teamwork, and relationships. An important idea is that, although involving storytelling into these spaces is valuable and brings a different perspective, respect for the people and communities doing the sharing is just as important. This is very crucial to building relationships and solidarity within communities and with people outside the community who want to work with the language.