Face/Politeness in Japanese

Humor in Japanese

Practical Ideas & Resources

Resources in this section curated by: Risa Miura, Kaleb Stubbs

Sarcasm in Japanese: How it Works | Blog Post

This blog post explains Japanese sarcasm in general, then compares it to English and provides examples of Japanese sarcasm with explanations. There are also links to other resources that further explain some key terms.

Degawa English | TV Segment

There is a popular TV series in Japan called Sekai no Hatemade Itte Q! One of the goals of the series is to explore places around the world and complete missions using English. The Japanese comedian Tetsurou Degawa has limited knowledge of English but tries to complete missions and find clues by communicating with locals. In a scene from London, he was trying to say the Japanese word zamaa miro, which means look at yourself. The subtitle of this phrase was written all in katakana characters even though zamaa is not a foreign word. The effect of subtitles was more sarcastic because of the way that Degawa uses the phrase mixing English and Japanese.

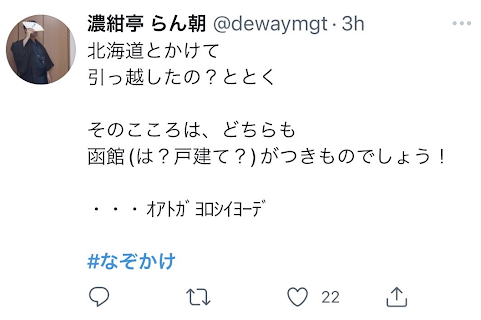

Post from @dewaymgt | Tweet

This is a great example for describing sarcasm by using deviate usage of the Japanese characters. At the bottom, it says ...oatoga yoroshii youde in katakana. The phrase sounds sarcastic as it means that's all from me. Because the phrase is derived from Japanese, writing it in katakana looks more sarcastic as it can imply distance, especially with the usage of ellipses at the beginning of the sentence.

5 Comedies that Best Explain the Japanese Sense of Humor | Article

Despite oft-repeated claims that Japan has one of the most homogenous societies on the planet, Japanese people and their culture are as diverse as any other nation on the planet. This extends to their sense of humor, which is multifaceted and varied; the best way to understand it is by watching Japanese comedies. This article suggests five comedies as a good starting point.

Unspoken Rules: How to Read the Air in Japanese Companies | Article

Reading the air is important in Japan, which contributes to a form of humor when someone is unaware of or cannot understand the unspoken rules of a group. It is especially popular with young people as slang to mock their friends or complain about annoying encounters. However, the concept of people being KY is one that often troubles Japanese companies—especially when hiring foreigners.

The “air” is invisible, therefore it cannot be described, yet is expected to be understood in order to maintain harmony. One who is not correctly reading the air can be easily spotted and may be the subject of a joke or scorn. Other terms, such as aun no kokyu, meaning being perfectly in unison, or anmokuchi, meaning tacit knowledge, are valued positively and recognized for requiring high levels of emotional intelligence. Unsurprisingly, those who are unable to catch an unspoken message can easily become an object of scorn.

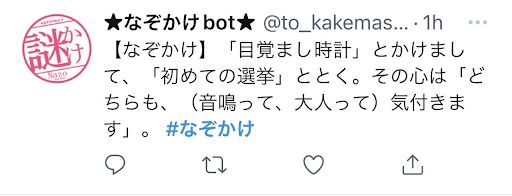

#Nazokake | Twitter Hashtag

A) Mezamashi dokei to kemashite

B) Hajimeteno senkyo to toku

(sono kokoroha)

Dochiramo otonatte kidukuimasu.

In this nazokake, the word otonatte has a double meaning: A) mezamashi dokei means an alarm clock and B) hajimeteno senkyo is the first election in one’s life in which one is able to vote. Both A) and B) make you realize by relating the word otonatte. Here, otonatte for A) means sounds from the alarm clock go off to make you wake up. Otonatte for B) means to make you realize that you are an adult (by law). However, Japanese use different Chinese characters to differentiate the two meanings and also change the tones.

100 Nazokake Questions | Article

好きな人と掛けまして 嫌いな人と解きます (その心は) どちらもはなしたくないでしょう。(話す/離す)

A) Sukinahito tokakemashite

B) Kirainahito totokimasu

(sonokokoroha)

Dochiramo hanshitakunaidesyou

In this nazokake, the word hanasu, which is a dictionary form of hanashi in hanashitakunaidesyou, has a double meaning. A) sukinahito means a person who you like/love and B) kirainahito means a person who you do not like. The punchline hanasu in this example has two ways to differentiate the meanings by using different Chinese characters. Hanasu in A) means to keep distance with; however, in the context of B), hanasu means to talk with.

Dad Jokes | Article

・内容が無いよう (naiyou ga naiyou)

There are no contents

・アルミ缶の上にあるみかん (arumikanno ueniaru mikan)

A mandarin orange on an aluminum can

・「アイスを食べよう」「あ、いっすね」(aisu wo tabeyou)(a, issune)

"Let eat ice cream" "Yeah, that sounds good"

・バスガイドに乗る前にバスが移動 (basgaido ga norumaeni basu ga idou)

A bus was moving before a bus guide got on

Although the translations don't deliver the same punch line as they do in Japanese, the sounds of the words that are used in the Japanese version sound almost identical and carry different meanings. This is a play on not only the sounds of the words, but the words themselves.

Table of Honorific Categories in Japanese | Image

This image shows the three of the levels of honorifics that are used in the Japanese language. The use of Keigo is the basis of understanding how sarcasm works. When talking to someone of equal status as you, 対等 "taitou" is used. When the listener is of superior status, 尊敬語 "sonkeigo" is used to honor that listener. In the same context, 謙譲語 "kenjougo" is used to humble yourself in front of that superior. By using 尊敬語 "sonkeigo" or 謙譲語 "kenjougo" in a situation that the two speakers are of equal status, this could imply that sarcasm is being used. Although this could represent genuine respect as well, depending on the context and gestures given, one could alter the illocutionary force of the utterance to imply sarcasm.

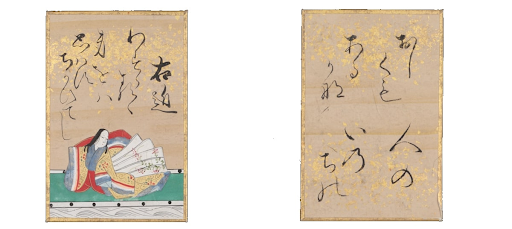

Ukon's Waka | Blog Post

The poet of this waka, Ukon, and her husband are breaking up after their marriage because the man was cheating on her. Instead of whining around all day, Ukon decides to express her emotion through waka using sarcasm.

「忘らるる 身をば思わず 誓いてし 人の命も惜しくもあるかな」-右近 (百人一首 第38番)

English translation:

Though he forsook me,

For myself I do not care:

He made a promise,

And his life, who is forsworn,

Oh how cruel it would be!

Emakimono | Manga

These are photos of the first ever manga written in Japanese history. Emakimono means painted handscrolls, which were the platforms for how manga first started. The interactions between frogs, a hare, and a monkey were intended to portray human characteristics in the form of animals. The first picture, named Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga (鳥獣人物戯画, literally "Animal-person Caricatures"), is considered to be the most famous and is one part of a set of four scrolls. These belonged to Kōzan-ji temple in Kyoto, Japan. It is believed to have been created by multiple artists. This was the beginning of an era of lively animations that were soon to follow and evolve into what we see now in today's manga and anime.

Neducchi's Nazokake | YouTube Video

Nazokake is a type of game of telling a riddle using words with the same or similar pronunciation but different meanings. There is a formula to tell nazokake in Japanese: (I came up with an idea) A x B (sono kokoro ha)= punch line. In Japanese, one says totonoimashita, A to kakete B to toku (Everyone else says) sono kokoroha, dochiramo (punch line). In the video, the Japanese comedian Neducchi, who is well known for his fascinating ability of telling a riddle, says:

Totonoimashita

(I came up with an idea).

(A) Dramu to kakete (B)waruikotowo suru to toku

(Drums and doing bad things)

(Everyone: sono kokoroha)

(Why is A like B?)

Dochiramo bachiga atarune

(Both bachiga atarune)

Therefore, bachiga ataru has double meanings: one is drums, drumsticks hit the drums, and the other is for waruikotowo suru, bachiga ataru meaning to incur divine punishment.

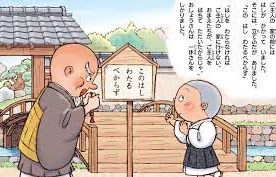

The board says "Konohashi wataru bekarazu" | Japanese Wit

Probably the most famous wit or tonchi in Japan would be "konohashi wataru bekarazu" from Ikkyusan. The two people in the comic get confused when they are invited by a man living across the bridge because the sign states, "do not cross hashi". Many assume hashi in this context means bridge. The little boy named Ikkyusan uses his wit to get to the man's place. Here, he and his master cross the bridge by understanding hashi as the edges, so they walk in the middle of the bridge. In Japanese texts, people differentiate those two homonym by using different Chinese characters and tones (橋/端).

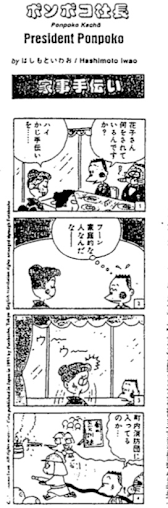

President Pompoko | Manga

In this manga, kaji is a keyword for understanding why the man misunderstood Hanako when she said the second line. Kaji is intentionally written in hiragana to let the reader guess which kaji Hanako is mentioning. In this conversation, kaji means either house chore or fire, so the man assumed that Hanako helps do house chores in her house. However, after she heard the siren, she changed her clothes to prepare for extinguishing the fire around her neighbor. Now, the man understands that Hanako does not help do her house chores, but rather assists the fire department team in her town.

Man: Hanako, what do you do?

Hanako: Yes, I help kaji......

Man: Hmm, how plebeian you are (despite the fact that her house and her clothes look fancy)

-Heard the siren -

-Hanako went to help the fire department-

Man: You are a member of the fire department in town…

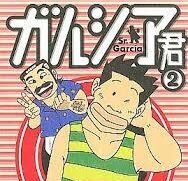

Garcia-kun | Manga

Garcia learned the implication of asameshi-mae, whose literal meaning is before breakfast, but whose idiomatic meaning is the same as a piece of cake. Although it seems he understood the implication from the context with woman 1, he misused and said asagohan-mae, which also means before breakfast. Here, meshi and gohan both mean meal(s), the former sounds more masculine but not formal. The latter is a neutral term; it is used by both genders. However, as an idiomatic phrase, it must always be asameshi-mae and not asagohan-mae. As a consequence, Garcia is offered breakfast by a random woman.

Garcia: You're good at flower arranging

Woman 1: It's easy. It's just a piece of cake

Garcia: ......okay

Woman 2: Oh, you are so strong

Garcia: Y, yes. It's before breakfast

Woman 2: Please have some meal

Garcia: ?

Summit School | Manga

In this comic, takusan, which means “many", is written in hiragana instead of normal hiragana or Chinese characters. At least the last two words that the students listed are one of the societal issues in Japan. Karo-shi means “die from work", and ijime means “bullying”. Here, takusan in katakana implies sarcasm because many words they know in Japanese provoke controversial problems in Japan, which makes Jiro scared to spend time with the students. Some of the classmates' hairstyles might also give Jiro an impression of them as scary people.

Woman: This is Jiro and he moved here from Japan

Students: We know many Japanese words

Sony, Honda, Sagawa, Kanemaru, Kenkin, karo-shi, and ijime

Jiro: Nice to meet you (with his voice shaking)

Sarari-man senryu from Daiichi Life Company | News Article

Every year, Daiichi-life company holds a large competition of original senryu. In this news article, there are examples of the top one hundred rewarded senryuu of 2021.

・ふところが 寒いもともと キャッシュレス - 船橋ブン

(Futokoroga samui motomoto kyassyuresu -Created by Bun Funabashi)

A Japanese idiomatic expression, futokoro ga samaui, means being short of money. Motomoto means originally and kassyuresu means cashless or non-cash payment. Non-cash payment recently began to be highly valued especially due to COVID, however, Japanese society has traditionally accepted cash only. Therefore, this senryuu has a sense of irony as it can be translated as “I am already living a humble life before the trend of cashless payment hit".

・バスケ・父 勝敗分けた リバウンド -(祝女子バスケ銀)

(Basuke・chichi syouhai waketa ribaundo -Created by Syuku jyoshi basuke gin)

In this senryuu, the Japanese word ribaundo implies two meanings: a ball rebounding in basketball and to regain weight. Therefore, this senryuu has a sense of irony. It can be translated as "my father was a basketball player, and rebaundo decided the winner".

・「シュウカツ」や 君はスタート 俺ゴール - (一枚岩)

("Syuukatu" ya kimiha syuta-to ore go-ru -Created by Ichimai iwa)

This senryuu employs a witty way of using homonyms. The author implies it by using the word syuukatu in katakana with a Japanese quotation mark, which can emphasize double meaning and/or sarcasm by giving readers some space to imagine its meaning and implication. In this senryuu, syuukatu has two meanings: job hunting and prepare for the end of one's life. Japanese differentiates the meaning by using different Chinese characters. Therefore, this senryuu can be translated as "you are on the start line of job hunting whereas I am heading towards the end of my life".

・巣ごもりで MからLに 服反応 - (ダイエット)

(Sugomoride M kara L ni fukuhannou -Created by Daietto)

This senryuu also utilizes the homonym of "fuku". Under COVID restrictions, the Japanese word sugomori became a bus word which literally means hibernation. The creator uses a different kanji for fuku in fukuhannou which means side-effects, so this senryuu can be translated as "Hibernation from society has changed my size of clothes from medium to large, and the clothes reflect the shift".

・テレワーク 解除で妻が 福反応 - (風信子)

(terewa-ku kaijode tumaga fukuhannou -Created by Nobuko Kaze)

This senryuu employs the same technique as the previous one, but it uses a different Chinese character for “side-effect”, even though it is pronounced the same as the original fukuhannou. In this case, the Chinese character for fuku means fortunate so this fukuhannou is not side-effect, but rather good-effect. Terewa-ku means telework, kaijo means to release or cancel restrictions, and tuma means wife. Therefore, this senryuu can be translated as "My wife looks happy after the cancelation of telework".

Oogiri from Syouten: #Zabutonichimai | Instagram Post

Oogiri is another type of Japanese humor where professional rakugo storytellers must give a witty reply to a question and get some laughs. During the performance, storytellers can get a zabuton cushion when they succeed to initiate big laughs. There is a long-running TV show called Shyouten in Japan, and whenever someone says somethings witty and makes people laugh, one may say "zabuton ichimai" which literally means "I will give you a zabuton cushion (as a token)", but it implies "that is a good one".

Even though rakugo or oogiri are not common things to enjoy among the younger generation, the phrase zabuton ichimai is still understood and used to add a sense of humor. The woman in the Instagram post is Yuriko Koike. She is the governor of Tokyo Metropolis, and is well known for spreading her message by coining a new word to draw people's attention, especially during the COVID pandemic. One of the new words she addressed to avoid meeting with people in a close distance is sanmitsu, which shares the same concept as 3Cs. Mippei (Closed-spaces), Missyuu (Crowed-spaces) and Missetsu (Close-contact settings). In Japanese, the first letter of all three key words are written in the same Chinese character, so she named this as 3 mitsu. This picture says "8 mitsu desu". The number 8 is pronounced hachi in Japanese, and hachimitsu means honey. That is why she is holding a bottle of honey in her hand.

“Rakugo” (The Art of Storytelling) | Article

Rakugo website is a type of Japanese comedy where the speaker tells a funny/interesting story while doing different voices for the characters in the story. It's a traditional form of stand up comedy, or in this case sitting. This is an important source to introduce a type of humor that is much different from western countries. There has also been a popular trend of foreigners doing this type of Japanese comedy.

Keigo (Honorifics) Example | Facebook Post

A woman from Kyoto uses keigo to say "kireina omeshimono yanee", which means "your cloth is pretty". In normal speech, you can say fuku to describe clothes instead of omeshimono. In this high context situation, the woman implies that it is not good on you (at all). Therefore, the correct response for this is to humble yourself by saying something like "No, I was about to change my clothes for going out". Otherwise, this woman would think that you are unsophisticated.

This is also a sarcastic meme of people in Kyoto, Japan. A woman says in Kyoto dialect, "yoroshiosunaa", which literally means "that is good" or "that sounds good". However, through the lens of illocutionary force, this actually means that "I do not care" or "I am not interested in it (at all)". Yoroshii is a type of keigo and in normal speech, Japanese people use "ii", which both mean "good". Since the woman uses yoroshii instead of ii, it sounds sarcastic. The correct response for this high context situation would be to change the topic.

A Canadian Rakugo-ka's Witty Take on Traditional Japanese Storytelling | Interview

This is a full interview of the first foreigner to be trained by a Japanese Rakugo master (Katsura Bunshi) to be a performer of Japanese traditional comedic storytelling. This is a Canadian man that has taken the name of Katsura Sunshine as his stage, and has performed both in Japanese and English. He has had to learn the Osakan Japanese dialect, because Osaka is the home of Rakugo performances. At the same time he has had to learn which stories are easier to translate and bring the same cadence and techniques that his master has taught him. This is an important perspective for learners of Japanese language, because they need to see that they have humor, its just that the rules and traditions are different from western countries.

【英語落語】オチまでカウントダウン?桂三輝の「ショート落語」| YouTube Video

This is a video by Katsura Sunshine, doing a brief explanation of Rakugo in English before he begins his performance. This is a good resource for teaching people who are learning Japanese about the rules of Rakugo with a short story as an example.

Craziest Japanese Pranks Compilation! LOL | YouTube Video

These pranks shows are similar to prank shows in other countries, as some of them are people pranking strangers. The main difference is that in many of these shows, there is a small screen that shows the live reactions of the hosts that are also watching the clip with the audience. The implication being that the viewers want to feel closer to the popular show hosts and laugh with them about the extravagant pranks. Students can watch the video and analyze the reactions and comments from the hosts watching the funny videos.

Apologizing in Japanese

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Masaki Eguchi, Yoshihisa Hirota

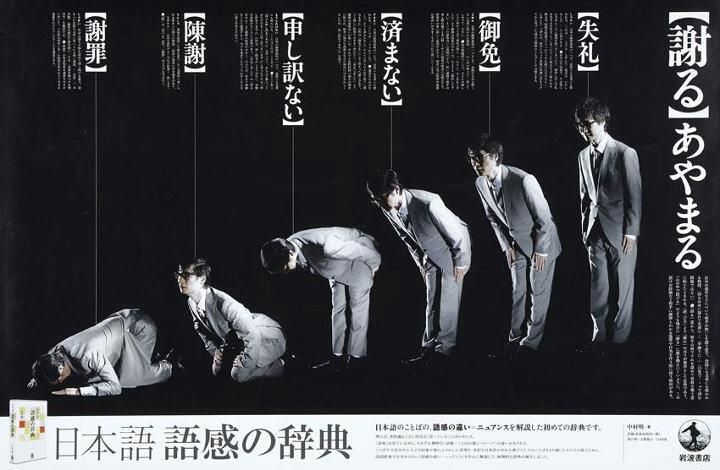

Bow Depending on the Situations | Image

This funny handout talks about how Japanese people bow according to the situations. This is not always true but we can raise students' awareness about the bow.

映画『謝罪の王様』オリジナル予告編 (The King of Apology) | Movie

The protagonist teaches how to apologize. That is his job. This is a comedy movie but students enjoy it while they can notice some differences in apology.

日本語「すみません」を正しくつかいます | YouTube Video

Anvill Videos -- UO ACCOUNT REQUIRED

Japanese apology 1 (meeting) | Anvill Video (UO Account Required)

Japanese apology 2 (to the boss) | Anvill Video (UO Account Required)

Role Play Situations | Activity

Card 1: You broke your friend's mug cup.

Card 2: You left your notebook in the classroom. Your classmate (you have not talked with him) brought it to you while you were walking out of the classroom.

Card 3: Your neighbor cleaned the street in front of your house.

Card 4: The train you were on was delayed for 10-15 mins. For this reason, you are late for class, and you need to talk to your professor after class.

Academic Resources on Humor in Japanese

Resources in this section curated by: Risa Miura, Kaleb Stubbs

De Mente, B. L., & Botting, G. (2015). Etiquette Guide to Japan: Know the Rules that Make the Difference! (Third Edition) (Revised ed.). Tuttle Publishing.

Maintaining harmony or 和 (wa) is a key staple in Japanese culture. Friction or irritation is considered taboo. This surface harmony takes precedence over others considerations. The essential part of proper behavior is to avoid being ashamed and shaming others as a result of behaving in an unacceptable manner. Stemming from a tale of old Japanese mythology where a god failed to follow prescribed etiquette and shamed his fellow gods and goddesses and was banned from the heavens, direct criticism towards someone's wrongdoing can potentially lead to more serious consequences. Thus to avoid criticism, people often use third parties such as a higher ranking individual or vague, indirect language to address a problem. It is also common to use humor to remove some of the sting while making a point.

Childhood training in Japanese etiquette was affected more through praise and example rather than threat of punishment. During infancy and childhood, praise is excessively given when acting appropriately (bowing correctly, using chopsticks properly, singing a song well, etc.) Once a person reaches teen years, expectations are higher and compliments become rare. However, praise can be overly used with foreign visitors who show an understanding of or skill related to Japanese culture (use of language, knowledge of proper etiquette). Even if someone is extremely good at something, an expert use of modesty is used to keep others from ostracizing them or being seen as arrogant. In this sense, sarcasm can be used to make that person stand out (overly praising them).

Gustafsson, J. (2010). Puns in Japanese advertisements. [Bachelor’s thesis, Lund University] https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1621551&fileOId=1621563

The author of this thesis argues that "The most probable reason why Japanese discourse is so packed with puns would be its remarkable abundance of homonyms and paronyms, which [] is one of the most basic conditions for creating a pun (p.22)."

Hayata, K. (2006). Statistical prosody: rhyming pattern selection in Japanese short poetry. Forma, 21(3), 259-273. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.620.2859&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Senryu was derived from waka, which consists of a word pattern of 5・7・5・7・7 , but senryu is limited to 5・7・5 words. “Although the syllabic structure of senryu coincides with that of HAIKU, this poetry is not bound by the stylistic requirements concerning the KIGO” (p.266) or a season word, and it became more popular among common folks and often included edgy sarcasm. Thus, senryu has now been enjoyed for a very long period of time.

Hudson, M. E., Matsumoto, Y., & Mori, J. (Eds.). (2018). Pragmatics of Japanese: Perspectives on grammar, interaction and culture (Vol. 285). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Honorifics must be used judiciously because they could be perceived as rude, distant, or insincere. Being careful about sentence endings is to consider the other’s feelings just like using honorifics. “By using expressions that are neither decisive nor assertive, you can make others feel that you are a calm and gentle person”.In contexts where the speakers are part of the same group (i.e., family or close friends), normally keigo would not be used and casual speech is even spoken to those older than you. However, when keigo is used in such situations, it creates somewhat of a sarcastic distance between the speaker and the listener. A similar phenomenon can be seen when someone is acting out of place or is being too arrogant. One might use honorifics to place that person on an imaginary pedestal as an attempt to embarrass them or make them stand out even more. This is why it is taboo to brag about one's own talents or accomplishments. In fact, the better someone is at something, it is more common and acceptable that the person uses a masterful technique of humbling themselves and keeping the harmony of the group.

Kumayama, A. (2010). The interrelation of Japanese language and culture. Global Business Languages, 2(1), 6. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=gbl

Often, American students encounter difficulty in learning the Japanese language. In addition to the grammatical differences that exist between Japanese and English, there are many cultural aspects of Japanese society that do not easily translate to American equivalents. In an effort to improve the learning process, many Western universities and business schools teaching Japanese as a second language have incorporated the study of language and culture together.

Kumayama mentions that "Since Japanese culture is high context in nature and American culture is relatively low context, it would be easy for an American student to misunderstand or miss some subtle contextual hints dropped by a native Japanese speaker (p.52)."

Maemura, Y. (2014). Humor and laughter in Japanese groups: The kuuki of negotiations. Humor, 27(1), 103-119. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0049

The authors of this article studied examples of naturally-occurring humor and laughter taken from simulated Japanese negotiations. Task-oriented negotiations were held in group settings, and participants were assigned conflicting interests to observe the occurrence of laughter in conflict situations. In-depth analyses of several negotiations were done in an attempt to reveal how humor and laughter are used to affect the negotiation process, and to shed light on how Japanese negotiators perceive and manage conflict situations. The study revealed that Japanese conversations are governed by a concept known as kuuki, and various types of laughter can be explained through the appropriateness of an utterance in relation to the implicitly defined kuuki of a social situation.

Moody, S. J. (2014). “Well, I’m a Gaijin”: Constructing identity through English and humor in the international workplace. Journal of Pragmatics, 60, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.11.001

Since globalization increases linguistic and cultural diversity in local business settings, workers from different backgrounds are faced with the challenge of negotiating a variety of social identities throughout daily workplace interaction. This study employed an interactional sociolinguistics approach to analyze discourse data from a two-day observation of an American in a Japanese company. English and humor are used by the intern and his coworkers to co-construct a gaijin ‘foreigner’ identity in a manner that yields positive interactional and social effects. This discursive manifestation of an outsider identity effectively facilitates interaction, providing a non-intrusive strategy for interruption and opportunities for language play, socialization, and laughter. Results shed light on how diverse backgrounds can be used as a strategy for communicating and building relationships across linguistic and social barriers.

Neff, P., & Rucynski, J. (2017). Japanese perceptions of humor in the English language classroom. Humor, 30(3), 279-301. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2016-0066

Despite humor being an educational tool in language learning contexts, questions of appropriateness, cultural sensitivity, and student expectations cannot be ignored. This is especially the case in a culture such as Japan, where the time and place for humor is often dictated by the social norms of warai no ba, or “laughter places.”

In order to better understand the role of humor from the Japanese language learner’s perspective, the researchers conducted a survey of 918 university students across Japan to elicit their views on the importance of humor for language learning and proficiency, as well as its significance in understanding cultural differences. Results indicated that most participants strongly favored inclusion of humor as part of the classroom experience but that cultural differences must be carefully considered by instructors. Furthermore, while variables such as gender and academic discipline did not have a significant effect on the results, the English proficiency of the participants did, with more proficient learners indicating a greater degree of comfort and cultural understanding from use of in-class humor than those with lesser ability.

Nishimura, S., Nevgi, A., & Tella, S. (2008). Communication style and cultural features in high/low context communication cultures: A case study of Finland, Japan and India. Teoksessa A. Kallioniemi (toim.), Uudistuva ja kehittyvä ainedidaktiikka. Ainedidaktinen symposiumi, 8(2008), 783-796.

People from different countries communicate in ways that often lead to misunderstandings. The authors’ argument, based on Hall’s theory of high/low context cultures, is that these differences are related to different communication cultures. The authors show how Japan and Finland belong to high context (HC) cultures, while India is closer to a low context (LC) culture with certain high context cultural features. “In an HC culture, the listener is expected to be able to read ‘between the lines’, to understand the unsaid, thanks to his or her background knowledge” (p.785).

The authors also contend that Finnish communication culture is changing towards a lower context culture. Hall’s theory is complemented with Hofstede’s (2008) individualism vs. collectivism dimension and with Lewis’s (1999, 2005) cultural categories of communication and Western vs. Eastern values. Examples from Finland, Japan and India are presented in the article.

Oshima, Kimie. (2013). An examination for styles of Japanese humor: Japan’s funniest story project 2010 to 2011. Intercultural Communication Studies 22(2). 91–109.

The focus of this study was to explain why Japanese humor tends to be used for inner circles, by creating an online website that collected funny story submissions from all ages and gender in Japanese. The study lasted from April 2010 to March 2011, and people were able to submit their stories and vote for their favorite ones. It was discovered that Japanese humor doesn’t like the convention of “ready-made jokes”, jokes that talk about imaginary people, and instead want funny personal stories, “omoshiroihanashi”. The reason being that these funny stories are shared between people that have a close relationship and can be more casual with each other. Some of the most popular types of stories were about culture/society, and words/language misunderstandings (pun, word play, interlanguage miscommunication).

This is important for our curation, because it showcases how humor can be vastly different from one language to the other. Not only in content but how humor is co-constructed and in what context it is created. That humor can be inappropriate used in different context and therefore, it is necessary to explicitly address these differences with pragmatics instruction.

Shinohara, K., & Kawahara, S. (2010). Syllable intrusion in Japanese puns, dajare. In Proceedings of the 10th meeting of Japan Cognitive Linguistic Association. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kazuko-Shinohara-2/publication/343319135_Syllable_intrusion_in_Japanese_puns_dajare/links/5f22e8b792851cd302c8cdfb/Syllable-intrusion-in-Japanese-puns-dajare.pdf

The authors state that "In composing puns (dajare), Japanese speakers create expressions using identical or similar sounding words/phrases. The correspondence between the two elements in Japanese puns can be perfect or imperfect." Oftentimes in Japanese humor, the use of homonyms acts as the base of a punch line where the sounds of the words may be the same, but the writing of the words differ and ultimately contain different meanings. This leads to words and phrases having double meanings which, in turn, can hold a comedic coincidence with a witty play on words. In addition, by spelling the words using a different writing system (using katakana instead of hiragana or kanji), one can change the tone of the words which reflects a different energy and adds a comedic effect.

Taguchi, N. (Ed.). (2009). Pragmatic competence (Vol. 5). Walter de Gruyter.

In the disciplines of applied linguistics and second language acquisition (SLA), the study of pragmatic competence has been driven by several fundamental questions: What does it mean to become pragmatically competent in a second language (L2)? How can we examine pragmatic competence to make inference of its development among L2 learners? In what ways do research findings inform teaching and assessment of pragmatic competence?

Takada, H. (1993). Pragmatics in second language acquisition in the case of learning Japanese. [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Montana]. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9141&context=etd

The purpose of this study was to test the second language acquisition of some forms of cross-cultural pragmatics. A questionnaire adopted from a study by Blum-Kulka (1982) was used to examine pragmatic mistakes or differences made by first, second, and third year students of Japanese. The learners were native English speakers. Results showed that interlanguage and language transfer were perceived on several of the questionnaire scenarios. For the second question, the length of studying Japanese had a slight impact, but most differences were observed in first year students. Second and third year students did not differ appreciably. The author presents three theories that may explain the pragmatic mistakes or differences made by the participants.

Takekuro, M. (2006). Conversational jokes in Japanese and English. In J.M. Davis (Ed.), Understanding humor in Japan, (pp. 85-98). Wayne State University Press.

For anyone interested in Japan, Japanese culture, and humor studies, Understanding Humor in Japan is an important teaching tool. It provides accessible, illustrative examples of humor in both Japanese and English with explanations of their meaning and cultural significance. Scholarly yet readable, these essays offer intelligent discussion on various topics, one of which is a chapter by Makiko Takekuro on conversational jokes.

It is often said that Japanese people lack a sense of humor. In order to find out what makes people say this, the author compares conversational jokes in English and Japanese, hoping to uncover some fundamental differences in communicative strategies between the two languages.

Uchiyama, H., Seki, A., Kageyama, H., Saito, D. N., Koeda, T., Ohno, K., & Sadato, N. (2006). Neural substrates of sarcasm: A functional magnetic-resonance imaging study. Brain research, 1124(1), 100-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.088.

Understanding sarcasm requires a complex process that involves recognizing the beliefs of the speaker. There is a clear association between deficits in mentalizing, which is the ability to understand other people's behavior in terms of their mental state, and the understanding of sarcasm in individuals with autistic spectrum disorders. This suggests that mentalizing is important in pragmatic non-literal language comprehension. To highlight the neural substrates of sarcasm, volunteers underwent functional magnetic-resonance imaging. The research findings indicate that the detection of sarcasm recruits the medial prefrontal cortex, which is part of the mentalizing system, as well as the neural substrates involved in reading sentences.

The authors explain that irony is characterized by opposition between the literal meaning of the sentence and the speaker's meaning. Sarcasm is used to communicate implicit criticism about the listener or the situation on occasions provoking a negative effect and is accompanied by disapproval, contempt, and scorn. It can increase the perceived politeness of the criticism and decrease the perceived threat and aggressiveness of the criticism or create a humorous atmosphere.

Wells, M. (1997). Japanese Humour (St Antony’s Series) (1997th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

This is not a book of jokes. It is about how people make rules about humor: what humor is, what it is not, what it should and should not be, when it should and should not be used, what type of humor is permissible and what type forbidden, what is good and bad about humor, and what should be considered funny and what should not. The book offers a framework for a general understanding of why and how societies make rules about the use of humor, and how those rules affect patterns of communication and the development of humor and comedy.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON APOLOGIZING IN JAPANESE

Resources in this section curated by: Masaki Eguchi, Yoshihisa Hirota

Barnlund, & Yoshioka, M. (1990). Apologies: Japanese and American styles. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(90)90005-H

Questionnaire study (120 Japanese, 120 American)

- In both countries, saying directly “I am very sorry” was the most popular form of apology.

- Second popular: Japanese preferred to do something for the other person. (compensation)

- American preferred to explain the situation

The analysis revealed statistically no reliable difference in forms of apology chosen by males or females in either Japan or America. With respect to mismanagement of time and incompetent execution of an assignment, each country apologized differently.

The person violates the norms surrounding the scheduling of events;

- Japanese preferred to say directly “I am very sorry”

- Americans preferred to explain the situation.

Failure to execute an assignment

- Japanese: compensation

- American: compensation + other forms of apologies

Associate

- Cultural differences appeared in apologies employed with superiors and subordinates, with closest friends, and with strangers. (There was no data on the article.)

Ide, R. (1998). "Sorry for your kindness": Japanese interactional ritual in public discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 29(5), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)80006-4

Ishihara, N., and Cohen, A. D. (2004) Strategies for learning speech acts in Japanese. Minneapolis, MN: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, University of Minnesota.

Lee, H. E., Park, H. S., Imai, T., & Dolan, D. (2012). Cultural Differences Between Japan and the United States in Uses of “Apology” and “Thank You” in Favor Asking Messages. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 31(3), 263–289.

Sandu, R. (2012). Su(m)imasen and gomen nasai : Linguistic devices marking Japanese apology expressions and emotivity. Language and Dialogue, 2(3), 339-362.

Sugimoto, N. (1998). "Sorry we apologize so much": Linguistic Factors Affecting Japanese and U.S. American Styles of Apology. Intercultural Communication Studies VIII-1.

This paper tries to find why many observers of Japan-U.S. communication believe that Japanese people are more apologetic than are U.S. Americans in terms of five language related factors.

The elusive sumimasen

- Ex. When people drop a pen and someone picks it up, American people tend to say “Thanks”, and Japanese say sumimasen.

- picking up the pen

- American: the other’s voluntary act of kindness

- Japan: this inconveniences the other by putting him or her in a position of having no choice but to pick up the pen.

- sumimasen: associated with apology far more strongly than with Thanks, but it means both

- Japanese take advantage of this elusiveness.

Arigato (Thanks) sounds as if the speaker considers himself / herself as deserving of the favor because it lacks the lowering function.

- Arigato is reserved for situations involving those very close to the speaker

Cultural perceptions of language

Style of apology

- Japanese tend to castigate themselves: emphasizing negative aspects of the situation, promising to repair the damage / not to repeat the same offense.

- For Americans, the excessive self-humiliation is taken as a sign of the speaker’s low self-esteem, and could even embarrass the apology recipient. (In America, castigating themselves is not encouraged.)

- In Japan, a message can but may not and need not always reflect reality.

- American people try to point out bright sides of the situation in their apologies. They believe that it makes the other feel better. →In Japan putting out positive aspects sounds attempting to escape responsibility.

- Japanese people exaggerate negative consequences of the offense without the fear that the other would feel worse. (the other person’s point view →Japanese people’s virtue)

Tolerance to repetition: American people strongly discourage repetition of the same words, while Japanese people are more receptive of such repetitions.

In L2 conversation: Every time they face the situation where they typically say sumimasen in Japanese, they say “I’m sorry”.

Use of Accounts: U.S. American apology usually includes accounts.

For Japanese it sounds “I’m sorry, but…” which leads them to believe Americans never apologize, or Americans don’t know how to apologize.