Imposition/Severity in Japanese

Apologizing in Japanese

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Masaki Eguchi, Yoshihisa Hirota

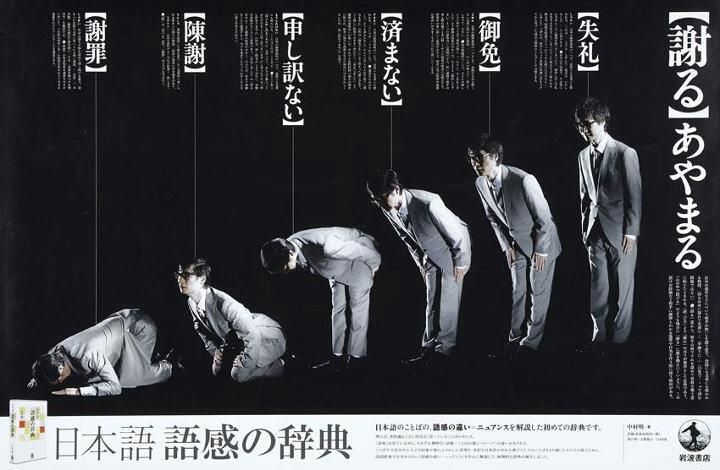

Bow Depending on the Situations | Image

This funny handout talks about how Japanese people bow according to the situations. This is not always true but we can raise students' awareness about the bow.

映画『謝罪の王様』オリジナル予告編 (The King of Apology) | Movie

The protagonist teaches how to apologize. That is his job. This is a comedy movie but students enjoy it while they can notice some differences in apology.

日本語「すみません」を正しくつかいます | YouTube Video

Anvill Videos -- UO ACCOUNT REQUIRED

Japanese apology 1 (meeting) | Anvill Video (UO Account Required)

Japanese apology 2 (to the boss) | Anvill Video (UO Account Required)

Role Play Situations | Activity

Card 1: You broke your friend's mug cup.

Card 2: You left your notebook in the classroom. Your classmate (you have not talked with him) brought it to you while you were walking out of the classroom.

Card 3: Your neighbor cleaned the street in front of your house.

Card 4: The train you were on was delayed for 10-15 mins. For this reason, you are late for class, and you need to talk to your professor after class.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON APOLOGIZING IN JAPANESE

Resources in this section curated by: Masaki Eguchi, Yoshihisa Hirota

Barnlund, & Yoshioka, M. (1990). Apologies: Japanese and American styles. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(90)90005-H

Questionnaire study (120 Japanese, 120 American)

- In both countries, saying directly “I am very sorry” was the most popular form of apology.

- Second popular: Japanese preferred to do something for the other person. (compensation)

- American preferred to explain the situation

The analysis revealed statistically no reliable difference in forms of apology chosen by males or females in either Japan or America. With respect to mismanagement of time and incompetent execution of an assignment, each country apologized differently.

The person violates the norms surrounding the scheduling of events;

- Japanese preferred to say directly “I am very sorry”

- Americans preferred to explain the situation.

Failure to execute an assignment

- Japanese: compensation

- American: compensation + other forms of apologies

Associate

- Cultural differences appeared in apologies employed with superiors and subordinates, with closest friends, and with strangers. (There was no data on the article.)

Ide, R. (1998). "Sorry for your kindness": Japanese interactional ritual in public discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 29(5), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)80006-4

Ishihara, N., and Cohen, A. D. (2004) Strategies for learning speech acts in Japanese. Minneapolis, MN: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, University of Minnesota.

Lee, H. E., Park, H. S., Imai, T., & Dolan, D. (2012). Cultural Differences Between Japan and the United States in Uses of “Apology” and “Thank You” in Favor Asking Messages. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 31(3), 263–289.

Sandu, R. (2012). Su(m)imasen and gomen nasai : Linguistic devices marking Japanese apology expressions and emotivity. Language and Dialogue, 2(3), 339-362.

Sugimoto, N. (1998). "Sorry we apologize so much": Linguistic Factors Affecting Japanese and U.S. American Styles of Apology. Intercultural Communication Studies VIII-1.

This paper tries to find why many observers of Japan-U.S. communication believe that Japanese people are more apologetic than are U.S. Americans in terms of five language related factors.

The elusive sumimasen

- Ex. When people drop a pen and someone picks it up, American people tend to say “Thanks”, and Japanese say sumimasen.

- picking up the pen

- American: the other’s voluntary act of kindness

- Japan: this inconveniences the other by putting him or her in a position of having no choice but to pick up the pen.

- sumimasen: associated with apology far more strongly than with Thanks, but it means both

- Japanese take advantage of this elusiveness.

Arigato (Thanks) sounds as if the speaker considers himself / herself as deserving of the favor because it lacks the lowering function.

- Arigato is reserved for situations involving those very close to the speaker

Cultural perceptions of language

Style of apology

- Japanese tend to castigate themselves: emphasizing negative aspects of the situation, promising to repair the damage / not to repeat the same offense.

- For Americans, the excessive self-humiliation is taken as a sign of the speaker’s low self-esteem, and could even embarrass the apology recipient. (In America, castigating themselves is not encouraged.)

- In Japan, a message can but may not and need not always reflect reality.

- American people try to point out bright sides of the situation in their apologies. They believe that it makes the other feel better. →In Japan putting out positive aspects sounds attempting to escape responsibility.

- Japanese people exaggerate negative consequences of the offense without the fear that the other would feel worse. (the other person’s point view →Japanese people’s virtue)

Tolerance to repetition: American people strongly discourage repetition of the same words, while Japanese people are more receptive of such repetitions.

In L2 conversation: Every time they face the situation where they typically say sumimasen in Japanese, they say “I’m sorry”.

Use of Accounts: U.S. American apology usually includes accounts.

For Japanese it sounds “I’m sorry, but…” which leads them to believe Americans never apologize, or Americans don’t know how to apologize.