Humor in Spanish

Humor in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Johanna Lyon, Cathy Lee, Tung Tuaynak, Jermayne Tuckta, and Ken Ezaki Ronquillo

How to be funny in Spanish /Como ser Gracioso, Formulas para añadir humor a tus conversaciones | Blog Post

This is a website in Spanish about how to add humor to your conversations. It explains different rules and strategies to develop your humor skills. It is written by a Spaniard psychologist that focuses on helping people be more social. This can be used as a resource to be read for a L2 Spanish course and to introduce strategies to create humor.

Social Media Humor | Image

This is an example of Spanish self degrading humor. Because the image focuses on the Facebook icons of messages and bell notification images. This case the person has one new message while they have 15 notifications. The messages are direct messages and not public posts. While the notifications can vary from people liking a public post adding new friends, incoming events, and etc. The phrase at the top says when you are ugly but funny. Thus, this type of person is able to get a lot of likes for being funny but has trouble getting a date with another person.

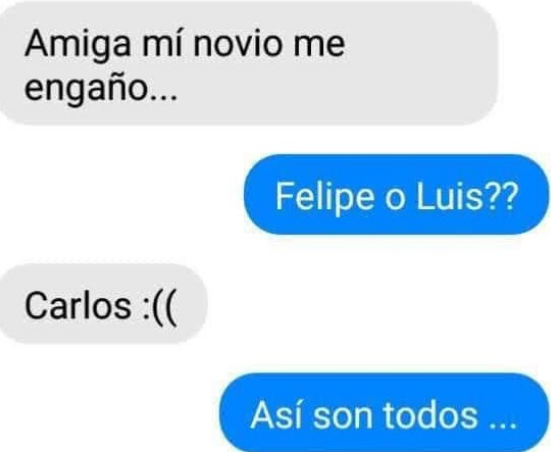

Text Conversation | Image

This is a conversation through Facebook between two female friends about how their boyfriend cheated with another person. The friend responded asking if it was Felipe or Luis, but the friend responded that it was Carlos who cheated. The friend responds by saying that everyone is like that. The funny thing about this meme is the irony that they are complaining of something that they are themselves doing. This can serve as an example that the students can use their cellphone/computer messaging to write their own funny/ironic conversations.

Pokemon | Memes

These two memes use a popular image from the anime series Pokemon, but use different tag lines to describe a slightly different context with the same punchline. The punchline being that another member has joined the group. The one in Spanish is talking about how the dirty plates in the room act when they see another plate being brought to the room. The one in English is the same but with bottles being brought to the room. There is a sense of comradery between the inanimate objects that represent bad habits of the person inhabiting the room.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON EXPRESSING EMOTIONS IN SPANISH

Resources in this section curated by: Nicole Williams

GENERAL RESOURCES

Dewaele, J-M. (2010). Emotions in multiple languages. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230289505

This book covers a wide range of topics related to emotions in multiple languages, such as the intricate role emotions play in identity construction (in the first and subsequent languages), expression, and social interaction. The book sheds light on the factors that can impact monolingual and multilingual language choices.

This is a great resource for building foundational understanding of research on emotions and the language we use to express them. Positing the idea that multilinguals learn to navigate the world in multiple ways, Dewaele delves into the complicated language systems speakers build and possess and the subsequent ways they choose to engage in the world and express themselves. The author also explores the implications of existing through more than one language and how that impacts the experience and expression of emotions.

Dewaele, J-M. (2011). Self-reported use and perception of the L1 and L2 among maximally proficient bi- and multilinguals: A quantitative and qualitative investigation. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 208(2011), 25-51. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2011.011

Interested in exploring the effect of emotional intensity and connection to a speaker’s first language (L1) and second language (L2) on expressions of emotions, Dewaele investigates the language choices of bi- and multilingual participants. The author draws upon past literature highlighting the choices bilinguals make when describing how they feel and how they perceive their emotions being portrayed as intensely as they desire in the L1 versus L2. Tied up in memories and experience, there is a general belief that bilinguals will default to the language that is most strongly connected to the emotional experience of a certain word or phrase (e.g., the difference between saying “I’m sad” and “Estoy triste”). Investigating participant-reported explanations for L1 or L2 choices to express emotions such as frustration, sadness, or love, several interview excerpts were analyzed to reveal a preference for the L1 to communicate feelings, even in cases where participants identified as equally using their L1 and L2.

The findings of this study are relevant for understanding how learners engage with the L2, especially in the classroom. While building up an emotional connection to the L2 can (and will) take time, often that emotional distance can be exacerbated when learners are focused on studying the language rather than acquiring the language. Thus, teachers could heed the findings in this study to create opportunities for learners to connect emotionally with the L2 in more than superficial ways. For example, rather than drawing lines connecting drawings to emotion words, questioning how they can create a context for learners to really experience said emotions words. Additionally, this study peripherally highlights frustration learners may feel at an inability to properly express themselves in the L2, especially if they feel they are disconnected and inauthentically being perceived. This article could spark interesting conversation around L2 identity construction and the importance of experimenting with language use in ways that feel genuine to the learners themselves.

Dewaele, J-M. (2013). Multilingualism and emotions. In C. A. Chapelle (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (pp. 1-7). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jean-Marc-Dewaele/publication/284179849_Multilingualism_and_Emotions/links/5a0e9bbf0f7e9b7d4dba6bc7/Multilingualism-and-Emotions.pdf

This article investigates an intriguing question: are emotions universally experienced or are they differentiated based on the language they are felt in? Dewaele draws upon past research on “language of the heart”, a term referring to the language through which we feel most intensely - the language that is deeply wrapped up in our encoded experiences. Generally, decisions over how to express emotions (in either the L1 or L2) were influenced by the intensity of the emotion and the identification of the language deemed as emotionally strong to convey that feeling.

This article offers reassurance and explanations of why we struggle to express ourselves in a way that feels “natural” and “authentic” in the L2. Learning a language is not simply memorizing set phrases and saying them whenever; the use of language is inherently tied to emotions. Our emotions often serve as impetus for choosing specific ways to express ourselves, and the choices we make can also reflect our personalities and identities.

For learners who are emergent bilinguals, this process of reconstructing emotional connections and building them with the L2 can be frustrating or exasperating. Having a teacher who can guide them through this - or even the knowledge presented in this article - and assure them that this is natural and expected could do wonders. It might also encourage learners to experience new things in the L2 to more easily build an emotional connection. Though the L1 is often the language of the heart, it doesn’t always stay that way - new, strong emotional connections can be established.

Dewaele, J-M. (2008). Dynamic emotion concepts of L2 learners and L2 users: A Second Language Acquisition perspective. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 11(2), 173-175. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728908003313

Here, Dewaele discusses pragmatic implications of L2 learners’ and users’ L2 usage. The idea of “emotion concepts” is first examined, which is the idea that there is a conceptual link between language use and illocutionary (i.e., speaker’s/user’s intended meaning) force. Each individual has created an emotion script which they call upon to decode and navigate interactions. The availability of an emotion script in the L1 or L2 can influence language choices in the L2, such that a person may choose to express themselves in accordance with their L1 emotion script because it feels more authentic. Essentially, while there might be an intellectual understanding of grammar and vocabulary in the L2, an emotional connection to the language (that is forged through experience in the L1) may impact how one chooses to react in an L2.

Understanding the influence of emotion and concept building in the L2 is crucial to developing as an L2 learner and L2 user. As a teacher, it serves as a reminder that sometimes what is spoken isn’t always felt - that learners may choose to express themselves in unexpected ways because it is more closely aligned with how they interact with the world in their L1. This knowledge can help explain the emotional distance a learner might experience in a relationship between themselves and the L2, and might bring awareness to how learners can overcome this if they feel it is a barrier to their ultimate language goals.

Dewaele, J-M., & Pavlenko, A. (2002). Emotion vocabulary in interlanguage. Language Learning, 52(2), 263-322. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00185

In an effort to uncover factors impacting the “use of L2 emotion vocabulary”, Dewaele and Pavlenko conducted two studies investigating variables of language proficiency, gender, extraversion, sociocultural competence, gender, and type of linguistic material. This study expands understanding of personal factors that may impact language use. Specifically, the authors investigate the acquisition and employment of language words in the L1 and L2 in relation to intensity of emotion experienced. The researchers analyzed corpora data in various languages, with an emphasis on emotion scripts and specific vocabulary used.

As with the other articles, this study lends itself to the understanding of learners and teachers that establishing an emotional connection with the L2 impacts use of the L2. Expanding on the idea that there is a relationship between cognition, emotion, and language the authors bring attention to the idea that even the words we use to describe our emotions can fall short at accurately and completely describing how we feel. This knowledge can serve as inspiration for teachers and learners to seek out information on different strategies to express their emotions in a variety of ways so they are not just limited to the few phrases included in their textbooks.

INTENSITY AND DEGREE

Czerwionka, L., & Olson, D. J. (2020). Pragmatic development during study abroad: L2 intensifiers in spoken Spanish. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 6(2), 125-162. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijlcr.19006.cze

Czerwionka and Olson analyze the frequency of use of intensifiers by expert Spanish speakers from Madrid and study abroad L2 Spanish-speaking students. Recognizing that skillful use of intensifiers requires a more advanced communicative competence rather than mere linguistic grasp, the researchers explore the change in use of intensifiers of study abroad students throughout a 6-week study abroad immersion in Madrid, as measured by frequency, lexical diversity, and collocation. Findings suggested that though there was no significant change in frequency of intensifier use, the immersion program did have an effect on intensifier lexical diversity (e.g., range of intensifiers employed by speakers) and collocations (e.g., “muy bien,” “bastante bastante diversa”).

While the findings of this study are rather dense and involved, there are a few key points to be gleaned. First, cross cultural differences in use of intensifiers is discussed and acknowledged. Second, there are a host of examples of collocations with common intensifiers provided in this study. Third, the discussion highlights the curiosity surrounding immersion programs and their impact on sociopragmatic development, for instance, in acquiring an expert-like handle of intensifiers. Finally, this study offers three important factors (intensifier frequency, lexical diversity, and collocations) which learners can explore in more depth to act as a triangulation of sorts in figuring out the appropriateness of using a specific intensifier.

Masullo, P. J. (2017). Exclamatives in (Argentinian) Spanish and their next of kin. In Bosque, I. (Eds.), Advances in the analysis of Spanish exclamatives (pp. 108-138). The Ohio State University Press.

This chapter focuses on the construction of exclamatives in Argentinian Spanish. Providing information on covert exclamations (and the use of specific prepositions and what they imply), Masullo lays foundational grammatical and syntactical information for how to construct exclamations in general. The chapter offers a linguistic analysis of sentence structure and different ways to express intensity and degree, illuminating the use of elatives (words ending in -ly), hyperboles, and reflexive verbs (e.g., “se comió todo”). The author concludes by emphasizing the variability that exists in constructing exclamatives - and the abundance of “attitudinal meanings” that are attached to specific formations (p. 137).

Though this article is abound with linguistic terms and analysis, it also offers a key point: grammar and vocabulary can be manipulated to express intensity and emotion. Gaining an understanding of the effect of a certain structure rather than just its conjugation or formation allows learners to correlate meaning with form. It also builds an awareness in learners that the forms we are taught in schools are not always representative of how creatively they can be used in the real world.

Ramon, N., & Labrador, B. (2008). Translations of “-ly” adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish parallel corpus. Target, 20(2), 275-296. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.20.2.05ram

This article investigates the translatability of “-ly” English adverbs to Spanish (and vice versa) in maintaining original meaning. They note that adverbs serve many roles, among them to express manner (e.g., the quality of an action, “I did badly”) and degree (e.g., the intensity of a verb, “It was poorly constructed”). Upon analysis of a corpora of fiction and non-fiction books, Ramon and Labrador examined the function of adverbs across both languages to identify similarities and differences. Findings suggested that there are “many-to-many relationship[s]” (p. 292) that can exist, with one adverb, “completamente” mapping onto several English equivalents.

While adverbs are commonly taught in classrooms as 1:1 translations in usage (e.g., meaning and degree), it is clear from this article that much variability exists. Importantly, the syntactic and pragmatic information that is encoded in adverbs underscores the importance of knowing which word in a phrase the adverb is modifying. Interestingly, while there are several ways in Spanish to form an adverb, it does not always involve tacking on “-mente” at the end of a word.

Not only does this article offer an in-depth analysis of the trickiness of direct translations and conveying similar meanings across Spanish and English, it also provides learners with examples of different Spanish options to form -ly adverbs. Understanding the ways in which adverbs can be used to express manner or degree can be helpful for learners should they use -ly words to augment expressed emotions. Thus, this article would be a great addition to expand upon adverbial knowledge being taught in a classroom and embed pragmatic awareness.

Roels, L. & Enghels, R. (2020). Age-based variation and patterns of recent language change: A case-study of morphological and lexical intensifiers in Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics, 170(2020), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.08.017

This work explores changes in the construction and use of intensifiers in Madrid in real time. Contingent upon the idea that intensifiers act as an extension of a speaker’s subjectivity (e.g., are bound in emotions and attitudes experienced by the speaker (p. 127)), Roels and Enghels examine generational differences in the use of morphological (e.g., suffixation or prefixation) and lexical (e.g., adding in specific words) intensifiers. They present instances of positive and negative adjectival intensifiers (e.g., “superconsciente” versus “una mierda”). Findings suggested some correlation between age and intensifier use, but mostly suggested the existence of a wide variety of intensifiers that are used across generations.

This article provides helpful information about how and why intensifiers are used in expert-like speech, emphasizing the creative license speakers employ when working in different intensifiers. Learners could use this article as inspiration for how to incorporate intensifiers into their own speech in a way that would help authentically express intensity and emotion. Detailing three main strategies - suffixation (e.g., augmentatives (“-azo”) or superlatives (“-ísima”)), prefixation (e.g., “super bien”), and other lexical strategies (e.g, “mazo de amor”) - the article provides grammatical and practical information (p. 130-131) learners can utilize and add to their linguistic repertoires.

Roels, L., De Latte, F., & Enghels, R. (2021). Monitoring 21st-century real-time language change in Spanish youth speech. Languages, 6(162), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040162

Curious as to the rate of change in language patterns in Spanish, the authors of this article hone in on youth speech. Specifically, the authors examine the speed at which youth speakers generated and used innovative language (e.g., intensifiers) through analysis of corpora data collected longitudinally from the same group of speakers. The authors highlight the amount of variety that exists in choosing to use intensifiers, for example, within a sentence, speakers can select from prefixes, suffixes, adjectives or adverbs or create more sophisticated intensifiers by stringing different parts of speech or clauses together. Findings suggested that the speed of linguistic change was not as dramatic as expected, however, there was evidence of certain forms and versions of intensifiers to remain stable in use or fluctuate more variably due to popularity.

Roels, De Latte, and Enghels offer direct quotations from dialogues registered in the corpora, presenting learners with a slew of examples to analyze in terms of context, topic, speaker identity, and purpose. This study is especially pertinent for learners who wish to express themselves in Spanish as presenting very youthful - or those who are generally interested in how young people their age choose to express intensity in Spanish. If anything, learners can pay attention to the diversity of forms intensifiers can take to then explore and use at their discretion.

METAPHORIC LANGUAGE

Kövecses, Z., Szelid, V., Nucz, E., Blanco-Carrion, O., Akkök, E. A., & Szabó, R. (2015). Anger metaphors across languages: A cognitive linguistic perspective. In R. Heredia & A. B. Cieślicka (Eds.), Bilingual figurative language processing (pp. 341-367). DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139342100.017

This chapter examines and compares conceptual metaphors for anger in four different languages. Drawing from corpora in American English, Spanish, Turkish, and Hungarian, anger metaphors were identified in terms of “metaphorical salience”. A detailed analysis is included of conceptualizations of anger and the types of things each language compares it to within the metaphor (e.g., rising of liquid, a weapon used in a fight, related to temperature/heat, pressure being released). Notably, Kövecses et al. draw attention to the emphasis on intensity and control as salient aspects of metaphoric expressions of anger, shedding light on how the four different cultures generally view and exude anger.

Though larger in scope, this article provides a great opportunity for the cross-cultural comparison of anger, emphasizing the idea that emotions are subjective and not universally experienced. The paper includes various examples of the metaphors, their functions, and how they might manifest in speech, while also providing cognitive commentary as to why anger might be expressed in such a manner in a particular language. Because anger can be a rather intense emotion, learners would benefit from understanding deeper cognitive connections and conceptual basis for a language’s or culture’s expression of anger in a specific way. Learners could also assess the kinds of metaphors they might use to express their anger and how it is similar or different from conceptualizations available in Spanish.

Paris, J. (2014). The expression of emotions by second language learners: Metaphor as a linguistic vehicle. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 50(1), 99-121. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2014-0006

Paris explores the use of metaphors to convey emotions and emotional states in writing by students with a first language (L1) of French and second language (L2) of English. Underscoring the complexity of emotions, especially when factoring in the inability to directly translate feelings from an L1 to an L2, Paris was interested in learners’ strategic use of metaphors to describe their feelings. Noting that the tendency to describe things non-literally is apparent in many languages, Paris contends that the words we use influence how we think and feel and vice versa.

Collecting writing samples from participants in the form of responses to prompts (e.g., “Could you live in a foreign country?”), Paris analyzed the samples for use of non-literal language (e.g., personification, comparisons, idioms, and metaphors). Findings suggested that L2 speakers of English sometimes employed metaphoric language to express emotions that might have been more difficult to directly translate from their L1. In this sense, the abstract helped convey the specific.

This article is comforting in its support of the idea that emotions are not easily translatable between languages. Moreover, in the act of translating emotions, sometimes the intensity is lost or lessened. Using this article as a means of raising awareness of this phenomenon, teachers and learners could explore the pragmatic function of metaphors. For example, knowing that L2 speakers chose to use metaphors to express their feelings - what affected this decision? Who were they speaking to? What were they speaking about? Why did they choose a metaphor as opposed to a simile or personification? The third person analysis of subjectivity is a great chance to think metacognitively about the language choices of someone else before applying that same line of thinking to one’s own choices.

Reali, F., & Arciniegas, C. (2015). Metaphorical conceptualization of emotion in Spanish: Two studies on the role of framing. Metaphor and the Social World, 5(1), 20-41. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.5.1.02rea

Rooted in conceptual metaphor theory - the theory that “language shapes thought” Reali and Arciniegas conducted a corpus analysis to reveal some metaphors related to emotional concepts. The researchers were interested in different emotion metaphors available in Spanish, as well as the impact of using metaphors to express an emotion in how that emotion is perceived. They chose to focus on two metaphors - “emotions are fluids in containers” and “emotions are bounded spaces” - to narrow the scope of the study. Spanning several genres of written text, the authors provide numerous examples of metaphoric language used to express emotion while drawing connections between the type of metaphor used and the quality of the emotion felt (positive or negative). Interestingly, “bounded” metaphors were more frequently used to describe negative emotions, such as “trapped in [emotion]” or “caer en [emotion]” (p. 31). Interestingly, the portrayal of an emotion as bounded versus fluid-in-a-container affected the perception of said emotion.

Similar to the other articles, this one proposes that emotions are not stagnant, removed experiences, but rather uniquely tied up in and affected by language. Understanding how a language and culture conceptualizes emotions through metaphors gives us a glimpse into how emotions are processed and experienced. Especially when considering the description of positive versus negative emotions, learners could do well to recognize the type of emotion metaphor being used and draw connections to the psychological state of the speaker. In the classroom, this article could prompt conversation around the complexity of emotions and the need for the acquisition of more strategies to express those emotions beyond simple words and phrases typically taught in textbooks.

Soriano, C. (2003). Some anger metaphors in Spanish and English. A contrastive review. International Journal of English Studies, 3(2), 107-122. https://revistas.um.es/ijes/article/view/48381

Contrasting the existence of certain metaphors and how they manifest in Spanish and English, Soriano explores attributions of differences between metaphoric conceptualizations of anger. For example, while there is a general similarity between comparing the experience of anger to fire, in English the effect of anger on the person is related to “steaming” while in Spanish it is related to “frying”. Additionally, Soriano describes discrepancies in the degree of anger expressed in both languages, drawing attention to the absence of direct verb translations in English or Spanish. Overall findings suggested that general conceptualizations of anger are similar in Spanish and English, though the specific metaphors that are created from these concepts can manifest in different forms (e.g., “boiling” versus “burning”). There also exists an imbalance in the variety of phrases in any one language related to a specific metaphor (e.g., there are several anger metaphors involving the devil in Spanish but not as many in English).

Though mistakes can be sources of great learning, Spanish learners could benefit from the knowledge that metaphors, especially, are not always directly translatable - and that they will have to go searching for more creative strategies to best express their emotions (ones that aren’t always present in their textbooks). It’s also useful as a guide to analyze the utility of a metaphor and its construction, with space for learners to explore more contextual factors that influence when, where, and why the metaphor may be employed. And, as with the other resources, this article provides some examples of metaphors that learners could adopt to express their anger in less literal, more figurative ways.

Soriano, C., & Valenzuela, J. (2009). Emotion and colour across languages: Implicit associations in Spanish colour terms. Social Science Information, 48(3), 421-445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018409106199

Soriano and Valenzuela investigate the tendency for emotional metaphors to map onto color-related conceptualizations of said emotions. The use of colors to express emotions is not unique to Spanish, though the particular emotions associated with specific colors may range from language to language. For example, anger is associated with green in Thai but red in English; green also connotes fear in French but boredom in Russian. The very associations humans arbitrarily assign to colors is a reflection of the cognitive conceptualizations of emotions. Soriano and Valenzuela study implicit color associations in Spanish using an Implicit Attitudes Test, extending upon previous research that looked at explicit, conscious associations. Participants were shown a color word and asked to categorize based on color, dimension (positive or negative), potency (powerful or weak), and activity (excited or relaxed).

Soriano and Valenzuela encourage readers to consider the arbitrary yet influential relationship between colors and emotions. A single color can have very different connotations attached to it when thinking and living in a specific language. It is not unusual, then, to extend this understanding to the struggle an L2 learner might experience at the muted emotional intensity with words in the L2. Precisely because many of our strongest associations with the world (e.g., in this case, with colors) is mediated through our L1, creating new connections and memories in the L2 is important to build up an equivalent intensity in the L2. Learners could use this article to build more awareness and cultural competence, and to remind themselves that language impacts how we see and experience the world.

DIGITAL SPACES

Fernández-Vallejo, A. M. (2018). Metáforas y emociones en el Twitter corporativo: Una aproximación discursivo-lingüística a los microblogs de Acciona e Iberdrola. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 73, 125-144. DOI: 10.5209/CLAC.59062

This study by pivots to the language use of two corporate entities, Acciona and Iberdrola. Collecting language samples from the Twitter accounts of these two companies, the researcher investigated the use of metaphors to elicit and provoke emotions in the context of marketing efforts. Tweets were categorized as either neutral or emotional, with a large majority of them being emotionally charged. Fernández-Vallejo found associations between the topic of interest (e.g., sustainability), the metaphor used, and the overall emotional quality attributed to the tweet (e.g., optimism, pride, etc.), with a larger amount of tweets being positively charged. Overall, there seemed to be an intentional effort on behalf of the corporations to evoke specific emotions with particular metaphors.

Tackling the Twitter space, this article equips learners with the basic understanding that words can influence emotional states - whether you are evoking or reacting to an emotion. It also provides a host of example tweets from Acciona and Iberdrola which learners could analyze further at the linguistic (e.g., what kind of vocabulary or grammar is present?) or pragmatic level (e.g.Who is the intended audience? How does the tweet create a sense of solidarity or distance between the company and the consumer?). Though this study does center on corporate use of Twitter, the takeaway that specific metaphors can evoke and capture certain emotions is one to note.

Maíz-Arévalo, C., & García-Gómez, A. (2013). ‘You look terrific!’ Social evaluation and relationships in online compliments. Discourse Studies, 15(6), 735-760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613490011

The authors of this article employ a new perspective on the speech act of compliments, exploring how they manifest and operate within social media spaces. The authors first lay down some foundation on how compliments are typically formulated, as well as the use of social media sites like Facebook to maintain and establish social bonds. Consisting of corpus data collected by the researchers of Facebook posts in Spanish and British English, analysis involved coding for three primary grammatical choices used to compliment including exclamatives, declaratives, and ellipticals. Connections were drawn between the type of grammatical compliment chosen and the emotion/intensity behind the statement. Attention was given to not only the ways participants chose to express themselves, but also how the compliments were taken up and understood.

This study offers insight into the nuances of online communication - and makes explicit reference to the difference between a speaker’s intent and the actual reaction of a listener. In revealing how different constructions of compliments might be interpreted, learners can make more informed decisions of how they wish to compliment. Moreover, the study offers a new lens on the strategy of complimenting to express emotion, exposing several ways that Facebook users, in Spanish and English, use compliments to “evaluate others and strengthen social rapport”.

Sampietro, A. (2019). Emoji and rapport management in Spanish WhatsApp chats. Journal of Pragmatics, 143, 109-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.02.009

Sampietro highlights the curious relationship between managing rapport and the use of emojis. Just like regular language, emojis serve communicative functions - some of which can be based on shared understanding or can develop out of an individual’s idiolect. Factoring into emoji (and linguistic) decisions is the management of rapport, that is, what feels appropriate? This could be impacted by the relationship between speakers, topic being spoken of, setting, etc. Analyzing a corpus of collected WhatsApp chats from Spanish speakers, Sampietro found four most common emojis used. Beyond their function to augment or complement the expression of emotions, emojis also serve to save face, manage conversations (e.g., starting or ending a conversation), and to signal speech genre.

From a language learning perspective, this article points to the importance of extralinguistic features, such as emojis, in the act of communicating and interpreting. Recognizing the difference in expected communication norms in online spaces (and in particular, via WhatsApp for this study), learners would benefit from knowledge about when, how, and why expert Spanish speakers use emojis, stylistic choices which may be different from a non-Spanish first language (L1) baseline. Though the use of pictures (emojis) may seem more straightforward, it is clear that emojis can serve a direct or indirect function, depending on the interlocutors’ intent. For learners interested in analyzing the linguistic patterns of texting or online speech, this article provides useful information on the function of emojis.

Yus, F. (2015). Attitudes and emotions through written text: The case of textual deformation in internet chat rooms. Pramalingüística, 13, 147-173. https://doi.org/10.25267/Pragmalinguistica.2017.i25

Given that language changes to fit the needs of those who use it, it is no surprise that language takes on a life of its own in online spaces. Specifically, Yus explores the creative language choices and concoctions of Spanish youth in Internet chat rooms, examining how they negotiate and convey meaning. In attempting to express emotions in a limited manner (e.g., solely with written words versus in-person use of body language and facial expressions), meaning is contingent on a language user’s ability to properly express their feelings and intent. What results is warping of texted language, transforming into almost a virtual expression of spoken connotations. For example, Yus uses Adroutsopoulos’ (2000) taxonomy to highlight six different changes spoken speech undergoes when it is conveyed via chat room in order to capture some of the personality and intensity it would otherwise have if spoken. Yus also brings attention to the function of punctuation in helping to properly express emotion and attitude (e.g., “oooo” versus “oooo!!”). Essentially, the lack of nonverbal information that is usually present in face to face conversations is compensated for using different texting strategies.

Learners could greatly benefit from this article just at the sheer amount of information it contains about Spanish texting conventions and their correlation to expressing specific kinds of emotion or tone. Learners could extend upon this research by searching for other examples of texting conventions that are not found in chat rooms (e.g., on social media or online gaming). A great example of learning how to analyze texting conventions is on page 22, which presents Table 3 and a variety of statements with possible intentions listed below. Importantly, the author notes that though there is much innovation in these online spaces, interlocutors should still take care to establish agreed upon norms in the use and interpretation of innovative texts.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON HUMOR IN SPANISH

Resources in this section curated by: Carla Consolini, Tigre Lusardi, Lorelei Pfeffer, Johanna Lyon, Cathy Lee, Tung Tuaynak, Jermayne Tuckta, and Ken Ezaki Ronquillo

Cordelia, M. (1996). Confrontational style in Spanish arguments: Pragmatics and teaching outlook. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 9(2), 148-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908319609525226

In this study the author sought to determine if second language learners of Spanish who speak the language in heritage or Spanish-dominant locations debate any differently than those who speak Spanish only in a classroom setting. A group of students learning Spanish at an Australian university were split into three groups (G1- students from Spanish-speaking backgrounds, G2 - students who had lived for a year in a Spanish-speaking country, and G3- students whose only exposure to Spanish was in a language learning classroom) to assess any possible differences in argumentative style between the groups. Each group was recorded individually while talking/debating about the same topic. Upon analysis of the recordings, the G1 and G2 groups, who both had exposure to Spanish outside of the classroom setting, employed similar confrontational style, including interruption, cooperative overlap during turn taking, and rapidly-timed stressed challenge questions. The G3 group employed a more non-confrontational style typical to Australian English, omitting Spanish style interruption, cooperative overlap and challenge questions and following an English style orderly turn-taking strategy.

The G1 and G2 groups had likely learned the confrontational style through speaking with native speakers encountered in their communities of families (G1) or during the study abroad experience (G2). Learners without the ability to interact regularly (and socially) with native Spanish speakers will thus need explicit instruction in Spanish confrontational style to be able to employ it successfully. The author concludes that, in a classroom of speakers from a variety of backgrounds, open debates can be useful activities for exposing learners to different types of pragmatic strategies in the target language.

Hidalgo-Downing, L., Hidalgo-Downing, R., & Downing, A. (2014). Strategies of (in)directness in Spanish speakers’ production of complaints and disagreements in English and Spanish, in A. Gomez Gonzalez, F. Mendoza Ibanes, F. Gonzalvez-Garcia, and A. Downing (Eds.), The Functional Perspective on Language and Discourse: Applications and implications. 261-284.

This study is a research into how students from a Spanish university use strategies on being indirect when expressing complaints, disapproval and disagreements, both in English and Spanish, through the use of role play. Results show that different strategies were used when speaking Spanish or English, showing that learners adapt their strategies depending on their understanding of the culture (English vs Spanish) they were participating in.

Pomerantz, A., & Bell, N. D. (2011). Humor as a Safe House in the Foreign Language Classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 148-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01274.x

In this article, Pomerantz and Bell observe a foreign language Spanish class at a private university where all students were at the intermediate-high level. The aim of the study was to see how humor was employed and the impact it had on language learning. Pomerantz and Bell observed and took notes on a 15-week course that met three times a week for 50 minutes each, and interviewed the fifteen students in the course as well as the teacher. Audio recordings were also used to compile data. They found that humor allowed students to saturate language with their own meanings beyond typical, repetitive activities the teacher was having them do.

Shively, R. L. (2013). Learning to be funny in Spanish during study abroad: L2 humor development. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 930-946. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12043.x

In this case study, the author used a language socialization lens to examine how a 21-year old second language (L2) Spanish speaker developed use of humor in Spanish while studying in Spain. Seven recordings of naturalistic conversations were made of this student speaking with his host family and with a fellow L2 learner from his university classes. The recordings were taken over the course of the semester the student spent in Spain. The author coded successful and failed attempts at humor for genre, function, mechanism, contextualization and topic. The student made 72 successful humorous utterances and 18 failed ones, and 78% of his humorous utterances occurred during conversations with his friend. Over the period of the semester, the student was able to produce more successful humorous utterances, and was able to employ a higher linguistic creativity in his attempts at humor.

Results point to the importance of L2 speakers being able to interact and develop friendships with L1 speakers in order to better understand how to successfully use the pragmatic tools needed to produce humor in the target language.

Shively, R. L., Menke, M. R., & Manzón-Omundson, S. M. (2008). Perception of irony by L2 learners of Spanish. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.5070/L4162005096

This study aims to look at how L2 learners of Spanish at three different levels of proficiency are able to interpret irony in Spanish. The participants were L1 speakers of English attending a public American university; they were in their second, fourth or sixth semester of Spanish study. The students’ interpretation of irony was tested through a written task or a video-enhanced task that used selected scenes from films in three different Spanish dialects as source material.

Analysis of the responses to both tasks showed that the accurate interpretation of irony generally rose as length of time of study increased. Lexical knowledge was key to the students’ ability to interpret ironic statements, as they were not able to correctly interpret statements if they did not know/understand key lexical terms within those statements. In looking at written versus video-enhanced presentation, the authors found that only the highest proficiency, sixth semester students showed a significant difference in the ability to understand irony in the video-enhanced task over the written one. The authors suggest that constraints on the capacity of working memory for the second and fourth semester groups might mean that interpreting irony in the video-enhanced task (a video clip in addition to written information) was challenging precisely because it involved two different kinds of input.

Shively, R. (2013). Learning to be funny in Spanish during study abroad: L2 humor development. Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 930-946.

This study used a socialization framework to look at the development of humor in Spanish for American students that went to Spain to study for a semester. To be able to comprehend and produce humor it is necessary to have a good foundation of linguistic, pragmatic, sociolinguistic, and cultural knowledge. The students need to understand why and how an utterance is funny. The study abroad students were put together with people with higher proficiencies with the language in order to be exposed to the input of humor in Spanish. The students lived with host families in Spain and there were also students from Puerto Rico that the students interacted with. The data collection was both quantitative and qualitative. Entire conversations with the host family and one Puerto Rican friend were recorded and analyzed. Some of the results were that the American student had some failed humor due to trying to translate his humor from English to Spanish. The student was able to get more explicit feedback from the Puerto Rican friend than the host family. The interactions with the other students improved when using humor, but had a limited amount of humor usage with the host family.

The implication for this study is that the students need to have more access to forming relationships with the locals when doing study abroad. But the implication for our collection is that there needs to be more explicit feedback on the usage of humor pragmatics, because humor norms are different in every language and context they are used in. Students shouldn’t need to travel to a different country to start getting explicit feedback on the pragmatics of language. It can be done by the language instructor back at home. With a background of pragmatic knowledge before traveling to another country will make it easier to learn how to interact with the locals from the get go.

Yus, F. (nd). Pragmatics of Humor in memes in Spanish. University of Alicante. Department of English Studies. https://personal.ua.es/francisco.yus/site/SiC.pdf

This author addresses memes in Spanish based on the relevance theory (Sperber and Wilson, 1995), and on previous work. The author addresses macro memes (images with text) and how it is necessary to decode the written text in the picture, and identify and understand the connection between the picture and the written text in it in order to comprehend the humor behind the meme. The research article lacks a proper analysis of the pragmatic intention behind the memes which, even though they aim to be humorous in general, sometimes carry a deeper meaning of the illocutionary force, such as a complaint, a social injustice, etc.