Face/Politeness in Spanish

Expressing Frustration in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS & RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Nicole Williams

BEGINNER

11 ways to express your frustration in Spanish | Blog Post

As beginners are looking to expand their vocabulary, it can be helpful to have written information to reference that offers details on explicit grammar points, examples, and context. This article does such a thing as it introduces learners to 11 common expressions of frustration that are used around the world. Not just centering Peninsular Spanish varieties, this resource includes expressions used in a variety of Spanish speaking countries and contexts. For some phrases, it also explains who might use the phrase and why, offering not only explicit grammar points, but pragmatic details as well. Additionally, while some phrases might be familiar, there is a good mix of metaphors or more illustrative phrases learners could employ to express their frustration. Notably, the article emphasizes reading carefully through the presented information so as to “find the right expression for your situation.” Thus, this is a great resource for beginners to start to unpack some of the pragmatic layers and think through intention as a speaker trying to convey frustration, and how to do so in a way that would reflect the intensity and authenticity of the feeling that is being experienced.

Spanish phrases to use when you're angry | Phrase Audio

This resource provides recorded snippets of 16 expressions or phrases to use when you are upset. While many of the other resources are written blogs, this site offers a chance for learners to listen to expert speakers pronouncing these phrases and words. Of note, it may be a particularly interesting exercise to compare the recordings of the phrases to how they would be used in real life - upon listening, some phrases are pronounced with the listener in mind as opposed to being spoken with real frustration or anger. More specific instruction in a classroom could cover differences in prosody in different settings and when speaking to different people. Ultimately, this resource offers audio examples of phrases instead of just written information - although it is best accompanied with more structured discussions about when, how, and why to use these.

Christmas in September, why not? Comprehensible input to learn Spanish | YouTube Video

This YouTube video, created by a channel called Spanish After Hours, is specifically made for beginner learners of Spanish. The creator pays careful attention to their tone, rate of speech, and clarity of pronunciation so as to produce comprehensible input that is still semi-authentic in context. The video is about the creator decorating their apartment, talking through putting ornaments on a small tree and setting up figurines. There are also Spanish subtitles that are put on the screen to accompany the audio. The phrases of frustration are spoken in a slightly different manner than other videos, as the creator is only speaking to the camera and expresses almost exasperation in laughter at some mistakes they make while decorating. This video would be great for beginners to get Spanish only input on an interesting topic that is comprehensible.

INTERMEDIATE

How to express anger in Spanish without being rude | Blog Post

This article provides a wealth of information on different strategies to express anger, including a note on false cognates, prepositions, adjectives, and sentences. There are detailed explanations of pragmatic information such as what preposition to use to express anger at someone or something, intensity of a phrase, and how you can use it with certain people (e.g., with friends). It also provides comparisons of direct English translations with different Spanish prepositions, adjectives, and verbs. It would nicely accompany instruction on the subjunctive mood and expands the verbs that would trigger subjunctive to express anger. The example phrases that they give are also contextualized with a hypothetical scenario in which you would use it. The article provides various forms of expressing anger that do not involve profanity (a feature boasted by the article itself).

9 ways native speakers express anger in Spanish | YouTube Video

This video was created by a YouTuber named Juan who creates videos for people interested in learning Spanish. A step further from written explanations, this video provides a variety of Spanish that is not often included in Spanish classrooms. Though it was created with learners in mind, various phrases are shared in the context of a short skit demonstrating how they might be used. Juan offers explanations and context in English before showing a skit in Spanish (though Spanish and English subtitles are shown during these skits). Special effects are included which emphasize the frustration expressions and how they are used. Notably, the expressions Juan includes are introduced with a slide that has the Spanish phrase, the English idiom/equivalent, and the literal English translation. This video would be a great way to expand on cultural competence by analyzing the pragmatics of this phrase and how it would be interpreted across Spanish-speaking countries, as well as the relationships that are shown in the video (e.g., one phrase was used with a stranger who was a marketer). Learners could also analyze the types of instances that trigger specific frustration phrases, relating to severity of an action.

Feeling mad? 28 expressions of anger for your bad mood | Blog Post

This article pays close attention to the importance of intensity and having words to express that intensity, relative to the appropriateness of a situation and how a person is actually feeling. Listing 28 expressions one can use to show anger or frustration, the article briefly explains (in English) the kind of context you would use this phrase in (in regard to intensity of anger felt), the English equivalent or direct translation, and sometimes an example. Though this list is limited in its explicit pragmatic descriptions, it can be used as a starting point to open discussion on when, with whom, and why one would use each phrase. The variety of expressions also lends itself to providing learners with a selection to choose from that best fits their needs, personalities, and how they wish to express themselves and their (intense) feelings. Lastly, this list incorporates phrases from Peninsular Spanish and Latin American Spanish dialects, creating an opportunity to cross-culturally compare phrases and their meanings.

ADVANCED

A list of Spanish slang expressions for ANGRY: 12 ways to sound like a local | Blog Post

This list of expressions of anger extends a learner’s vocabulary from set academic phrases to slang phrases one might find in various Spanish speaking countries. Instead of limiting one’s repertoire to “enojada” or “furiosa,” the list helps learners express more intense manifestations of anger in more colorful, creative ways. Sometimes we are direct with our explanations of feelings, and sometimes we pull on different strategies to more indirectly or metaphorically express ourselves. One limitation of this source is that it only offers the specific phrase and a short explanation in English of the literal meaning and why one might use it. As such, learners and teachers should take care to do more research on these phrases and how they might be used in real life.

Cuando tu amigo y su novia discuten delante de ti | YouTube Video

Involving a variety of Spanish not always included in the Spanish classroom, this video uploaded by a popular Spanish-speaking YouTuber named Ibai records an interaction between a friend and his girlfriend getting into an argument. Expressions of anger fly left and right out of both the boyfriend’s and girlfriend’s mouths as they argue over dinner reservations, getting there on time, and saving face in front of friends. This video is particularly interesting to analyze, as there are multiple layers of pragmatics related to boasting in front of friends, gender effects of communication, relationship dynamics in a couple, and intensity/prosody of anger expressions. A larger conversation on relationship scripts and expectations (and how those are portrayed linguistically) could be touched upon in class to properly analyze the video and its content.

Making Direct and Indirect Requests in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS & RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Anna Krinitsyna, Anne Walkup, Isabella Walters

Making a Polite Request | Webpage

This article explains how to make polite requests with varying degrees of directness. Level of directness often depends on where you are, who you are talking to, and what type of request you are making.

Making Requests in Spanish: Vocabulary & Expressions | Video

This video explains a variety of ways one can make a request. The main character in the video is a Spanish learner who discovers that certain forms of requests tend to be taken better in some situations than in others.

How To Make Commands and Requests in Spanish Without the Imperative | Webpage

Sometimes, commands are the best option in Spanish for giving more direct requests. This article outlines some common ways of using commands to make requests when directness is appropriate.

How to Order Drinks | YouTube Video

A common example of a direct request is "yo quiero," followed by a food or drink. While this request may seem impolite, it is completely acceptable and even expected. This and other common requests are discussed in this video.

How to Make a Hotel Reservation in Spanish | YouTube Video

A common situation in which someone would use an indirect request is when booking a hotel room. In this video, the phrase "quisiera un cuarto con baño privado" is used to request a room with a private bathroom. While she does not directly ask for a room, the woman in the video effectively communicates what she wants by hinting at it with an indirect request.

How to Make Polite Requests in Spanish | Webpage

This article discusses various indirect phrases to make polite requests, such as "quisiera" and "me gustaría," both of which are polite but are used in different contexts. "Podría," "a ver si," and the use of "por favor" are also discussed.

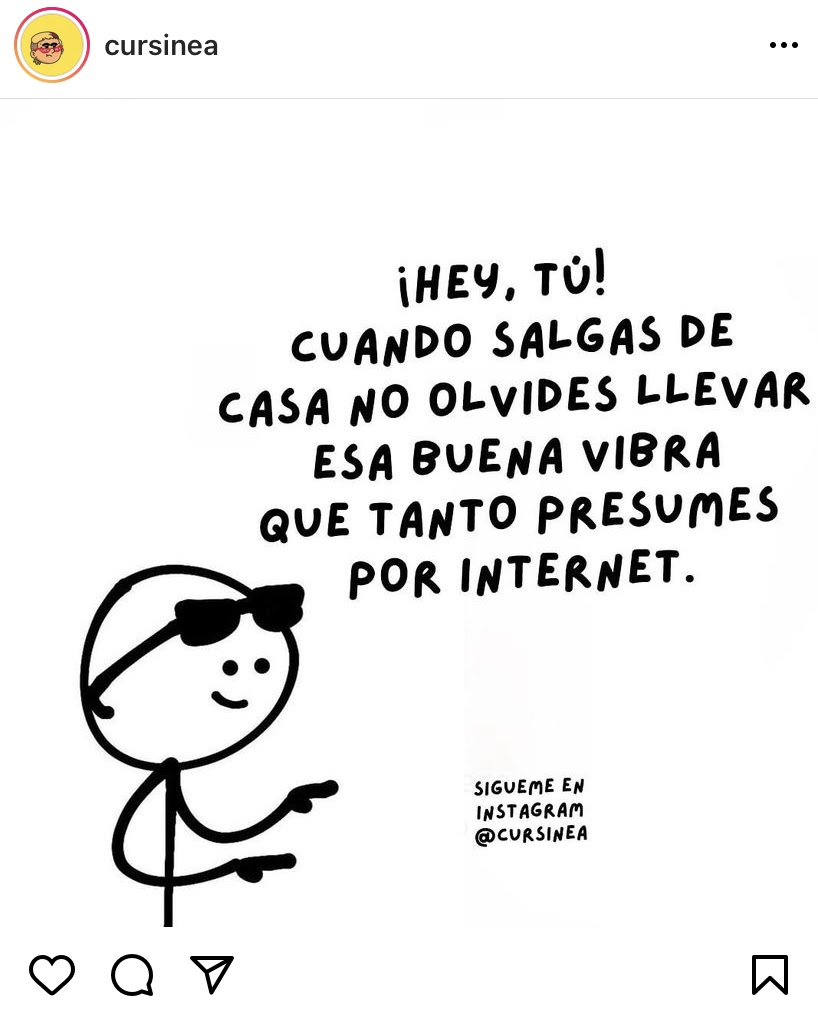

Image Example | Instagram Post

This Instagram post by @cursinea demonstrates a situation in which an indirect request would be appropriate. The character is requesting that whoever is reading the post have a positive attitude in their day-to-day life, rather than only show positivity on social media. Because this is more of a suggestion of what someone else ought to do, the present subjunctive tense is used to form an indirect request.

Making a Request in Spanish | Image

This graphic explains how to ask someone to do something for you. Person 1 uses "puedes" as a hedging technique, which results in a more indirect request. Her second request, "Necesitamos..." is even less direct since it is presented as more of a hint at what person 2 should buy.

'Dancing with Words' | Lesson

This website is a comprehensive resource dedicated to Spanish pragmatics. It includes lessons for various speech acts, including requests. It can be used for self-study and as a supplement in the classroom context with adults (and possibly high-schoolers). Learners interact with the page by reading text, watching videos and entering answers in text-entry question boxes. This lesson starts with a study of requests, then covers strategies, then social factors. It even takes a look at dialectal variance and ends with a summary.

CARLA: Pragmatics and Speech Acts | Webpage

The Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (CARLA) has created a wonderful resource for studying the pragmatics of different speech acts, including requests, in different languages, such as Spanish. This is a direct link to information about requests in Argentinian Spanish. While there is not a lot of information included on this page, there is an example of a direct and an indirect request and a citation to a scholarly article on the topic.

Making Service Requests in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS & RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Anne Walkup, Isabella Walters

Making requests in Spanish | How to use the word QUISIERA | YouTube Video

Quisiera is the imperfect subjunctive form of querer. It is an indirect request used mostly in a service context. This video explains appropriate ways in which quisiera can be used to make a service request in Spanish.

How to order food in Spanish - Español nivel intermedio - avanzado | YouTube Video

This video reviews, in detail, a service encounter in a restaurant in Colombia. Maria uses the phrase "hágame un favor" to initiate her request, followed by "me da un(a)..." which is a direct request. One may think that a direct request cannot also be polite, but this is not the case. She uses the usted form of dar in this request, addressing the cashier with respect, while still not sounding too formal. She also discusses how phrases like "me gustaría" and "me podría" are grammatically correct, but may sound less natural than desired in a service setting.

In some varieties of Spanish, it is common to use the verb encargar when ordering food and drinks. For example, one could say to a waiter, "Te encargo una limonada," which would be considered a polite yet not overly formal way of ordering a drink. This construction is mostly used in Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica. The article outlines further examples. In other cases, such as in Spain, using an informal command is preferred: "Ponme un cafe con leche." Simply stating what you want is not considered rude either: "Un cafe con leche, por favor."

From Coffee to Shots: How to Order Drinks in Spanish Like a Local | Blog Post

Ordering drinks in Spanish is completely different from ordering drinks in English. According to the blog post, it is widely common to order drinks directly. In a bar setting, typical phrases include "tomo," "dame," "quiero," y "ponme," followed by a drink. The same is true when ordering a coffee. It is also common to refer to drinks by their brand names, such as when ordering a soda. You're more likely to hear "Dame una Coca-Cola/una Fanta/etc." than "yo quisiera un refresco."

Real Spanish conversations: in the taxi/en el taxi | YouTube Video

A tourist from Canada requests a taxi ride in Mexico. She says, "Quiero ir al hotel San Miguel. ¿Me puede llevar?" She addresses the taxi driver both directly and formally, with the usted form of poder. They make friendly conversation for the rest of the ride.

Check-In at Your HOTEL in Spanish: ALL Phrases You’ll Ever Need | Webpage with Video

This video and accompanying description covers many phrases you would use to check into a hotel or Airbnb, everything from requesting a certain type of room to asking for a replacement key or the wifi password.

Apologizing in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Illena Trebont

20 Ways to Say Sorry in Spanish That Aren’t Just “Lo Siento” | Blog Post

Most Spanish L2 learners learn that “lo siento” as the only way to apologize in Spanish. In reality, native Spanish speakers use “lo siento” only in limited circumstances such as expressing sympathy or apologizing for a severe offense. Native speakers use other verbs such as “disculpar” and “perdonar” in circumstances where “lo siento” is not appropriate. This article walks learners through how and when to use apology phrases in Spanish and their different connotations.

General Appropriateness in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Illena Trebont

Strategies for Learning Pragmatics in Spanish | Article

Based on empirical research about Spanish pragmatics, this website provides comprehensive information and instruction about various speech acts in Spanish such as apologies, complement sequences, leave taking, etc. The website provides students with interactive activities and videos to aid their comprehension.

A Brief Guide to Regional Variation of the Forms of Address (Tú, Vos, Usted) in Spanish | Article

Most Spanish learners in the US learn to use tú, usted, y ustedes as second person pronouns. However, many people in the Spanish speaking world use the pronouns vos y vosotros. This article summarizes which pronouns are used in which regions and the pragmatic connotations in different countries.

Manners in Spanish – The Basics of Being Polite in Spanish-Speaking Cultures | Article

This article describes how Spanish linguistic politeness differs from English and gives learners guidance about how to greet people, use titles, and speak on the phone. It also gives students some advice about speech acts that can differ from English such as making requests.

Invitations in Spanish

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Illena Trebont

Invitations in Spanish | Article

Spanish invitations differ from English invitations in various ways and are often difficult for native English speakers to navigate. This webpage, authored by CARLA (Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition) reviews research on Spanish invitations and explains the structure and strategies that native Spanish speakers utilize to make invitations. The article explains aspects of Spanish invitations that are different from English invitations such as ritual refusals, varied refusal and insistence strategies, and the head and supportive acts associated with invitations. Because invitations, especially invitation refusals, can be face-threatening acts, it is important for Spanish learners to have the knowledge to navigate Spanish invitations to build relationships.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES FOR MAKING REQUESTS IN SPANISH

Resources in this section curated by: Anna Krinitsyna, Anne Walkup, Isabella Walters

Bachelor, J. W. (2018). Developing pragmatic competence in first-year Spanish students: a study on requests. MLS Educational Research, 2(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.29314/mlser.v2i2.73

Jeremy Bachelor explains the importance of teaching pragmatics in a language classroom that is communicative-oriented. He recommends starting in the first semester. In this article, he proposes how and why to teach requests from a pragmatic perspective in the first year of study. First, they are one of the most frequently used Spanish speech acts. Second, they can actually be introduced in a way that novice learners can understand.

Various pragmatics strategies and social factors are analyzed in this study, and scenarios are given. This would be a helpful article to teachers who are planning a lesson or a curriculum. Whereas 100 years ago teaching languages was mainly focused on translating literature, it is now the norm to teach language in order to principally communicate. Most Spanish textbooks with a communicative approach pay very little attention, if at all, to pragmatic principles. Researchers found that making requests in Spanish is one of the most frequently used speech acts and can even be threatening to one’s image. Speech acts are statements or expressions which play a specific role in communication. They include apologies, requests, invitations, and much more.

Bataller, R. (2010). Making a request for a service in Spanish: Pragmatic development in the study abroad setting. Foreign Language Annals, 43(1), 160–175. https://www.proquest.com/docview/871903181?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:primo&accountid=14698.

This article explores whether foreign language study abroad students improved in their use of Spanish pragmatics, specifically when making service-related requests. Prior research had elicited mixed results, with some studies showing improvement in certain pragmatic areas while other studies show no clear indication of any pragmatic development. This study found that in general, participants reduced the use of nonnative-like strategies that likely were the result of negative transfer, such as the query statement (Puedo…?) or the need statement (Necesito…). At the same time, most were not able to develop the most frequently used monolingual strategies, such as the simple interrogative (Me pones…?).

These results demonstrate some of the core differences between the pragmatics of Spanish vs English requests. They also indicate that certain pragmatic features are not likely to be picked up implicitly by L2 learners, and that more explicit explanation may be necessary for them to be developed.

Bertomeu, P. (2019). Requests in Spanish and German colloquial conversation: an approach to their types and forms. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, (79) 139-160. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA604315001&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=15764737&p=IFME&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E1bdc90fe.

The primary aim of this study was to compare request strategies commonly used in Spanish and German. To do so, researchers analyzed clips from two similar reality TV shows, Gran Hermano 17 (Spain) and Big Brother 12 (Germany). Of particular interest were the similarities and differences in terms of level of directness used in each language. Both languages made use of direct and indirect requests in particular situations, but overall, direct requests occurred more frequently in the Spanish version of the show than in the German version. This article contains examples of Spanish requests that could be used in instruction.

Bou-Franch, P., & Lorenzo-Dus, N. (2008). Natural versus elicited data in cross-cultural speech act realization: The case of requests in Peninsular Spanish and British English. Spanish in Context, 5(2) 246-277. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.libproxy.uoregon.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=9c949dae-a4d4-4c9c-aeff-3f8c365eb5da%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=35026214&db=zbh.

This article compares Spanish and British graduate students’ request strategies in both elicited and natural forms of speech. There were some noticeable differences in the two groups’ strategies–British students tended toward indirectness while Spanish students tended toward directness. Even more noteworthy were the differences in the elicited vs natural speech for both groups. The elicited speech produced different structures and levels of politeness than the natural speech did, which served as an indication of the importance of practicing requests in authentic settings.

Cuza, A. & Czerwionka, L. (2017). A pragmatic analysis of L2 Spanish requests: Acquisition in three situational contexts during short-term study abroad. Intercultural Pragmatics, 14(3), 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2017-0016

Even though this research was done with study-abroad (SA) learners, it has important implications for all learners on making requests in Spanish. Pragmatic strategies are used to carry out requests. A request is a speech act in which the illocutionary (intended) purpose is to get the listener to do something. A request can range from being very direct (like a command), to simply being a hint. We usually choose the strategy that is considered to be the norm and the expectation in our community, based on the context we are in.

The three most common situational interactions for SA are: food and drink, general merchandise or services, and familial interactions. Because English and Spanish speakers have different strategies for making requests, it is important to point them out to learners. It turns out that learners in SA contexts do not automatically acquire pragmatic competence. This article provides plenty of examples of speaker and hearer-oriented requests related to the three situational contexts.

Czerwionka, L., & Cuza, A. (2017). Second language acquisition of Spanish service industry requests in an immersion context. Hispania, 100(2) 239-260. https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.uoregon.edu/stable/26387777?sid=primo&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

This study examines the pragmatic development of a group of L2 Spanish learners studying abroad for six weeks in Madrid. The study focused specifically on request making strategies, and although no explicit instruction or intervention occurred during the time they spent abroad, the results indicated that learners still managed to improve in their pragmatic competence by the end of the six weeks. The researchers focused specifically on how learners adapted their request strategies to adjust for power, distance, and severity.

Dumitrescu, D. (2015). Pragmatic and discursive aspects of the U.S. Spanish. Informes del observatorio, 15(11). https://cervantesobservatorio.fas.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/015_reports_pragmatic_discursive_us_spanish_1.pdf.

In a study with speakers of Mexican Spanish, U.S. English, and heritage speakers (HS) of U.S. Spanish, the verbal behavior of the HS was more similar to the U.S. English speakers than to Mexican Spanish speakers. In the case of requests, HS were intentionally indirect when asking a roommate to clean the room, as opposed to Mexican Spanish speakers. In the scenario of requesting notes from a classmate, HS also tended to adhere to an English syntactic pattern, with phrases such as “¿Estaría bien si me las prestarías?” instead of phrases used more commonly among monolingual Spanish speakers. The study highlighted that HS in the U.S. tend to use more indirect requests in scenarios in which speakers of Mexican Spanish generally use more direct speech.

Félix-Brasdefer, J. (2005). Indirectness and politeness in Mexican requests. In Selected Proceedings of the 7th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium, ed. David Eddington, 66-78. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. http://www.lingref.com/cpp/hls/7/paper1087.pdf.

This study takes a look at indirectness and politeness in Mexican requests. A request is considered a pre-event to the negotiation of face in a conversation and serves as a threat to a person’s negative face (freedom of action). Two types of indirectness are discussed in the article: Conventional indirectness, which relies on literal speech, and non-conventional indirectness, which relies on the context. The study found that conventional indirectness was most common in situations with + Power or + Distance, while directness was more commonly used with - Distance. Conventional indirectness was used as a means to balance clarity and politeness.

Unlike previous research that supports the notion that indirect requests are considered more polite and face-saving because they increase the degree of optionality and are less forceful, direct requests are actually expected and welcome in most varieties of Mexican Spanish.

Félix-Brasdefer, J. (2006). Linguistic politeness in Mexico: Refusal strategies among male speakers of Mexican Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics, (38) 2158-2187. https://www-sciencedirect-com.libproxy.uoregon.edu/science/article/pii/S0378216606001329.

This study examines the regional variations of requests made by male university students in Oaxaca (MX), José (CR), and Santiago (DR). The focus is on power and distance relations, and the interactions were categorized according to the following head acts: Direct, conventionally indirect, and non-conventionally indirect. Other factors that were studied include differences between initial and post-initial requests, as well as different types of downgraders. The findings support that across all three regions, conventional indirectness was more common in the initial request and the post-initial request was impositive, with an involvement face. The most frequent request strategies were the imperative and the query preparatory. Regarding the regional variation of requests, the Dominicans tended to use imperatives, followed by want statements, more than the Mexicans and the Costa Ricans in the study. In Mexican Spanish, quasi-imperatives were often used covertly, without a verb. These regional variations, among others, cannot be generalized to all speakers of these dialects but still give a good idea of some of the differences in the pragmatics of requests across regions.

Félix-Brasdefer, J. (2010). Intra-lingual pragmatic variation in Mexico City and San José, Costa Rica: A focus on regional differences in female requests. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(11) 2992-3011. https://www-sciencedirect-com.libproxy.uoregon.edu/science/article/pii/S0378216610001116.

This article highlights the differences between requests in Mexico City (MX) and San José (CR). The study observes power and distance relations among female participants. Conventional indirect requests predominated, but regional differences were apparent in the type of strategy used and internal modification. The Mexicans in this study used a query preparatory equally with the future and conditional, while the Costa Ricans preferred the suppositional future. The Costa Rican participants also used significantly more internal modification than the Mexican participants. To account for pragmatic variation based on gender, the results of this study are discussed in relation to a similar study conducted with male participants and add to the overall body of research on pragmatics.

García, M. J. B. & Bachelor, J. W. (2018). Pragmatic instruction may not be necessary among heritage learners of Spanish: A study on requests. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Technology, 3(1), 163–193. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577580.pdf

The research conducted in this study focuses on the pragmatics skills of Spanish heritage speakers and seeks to determine 1) whether there is significant pragmatic transfer between English and Spanish request strategies, and 2) whether this learner population benefits from Spanish pragmatic instruction. The heritage learners (HLs) were compared to a group of second language (L2) Spanish learners to determine results. Results indicated that there is positive transfer for HLs, and because of this, pragmatic instruction in Spanish is unnecessary for them, since they already implicitly understand differences.

Even though the authors found that English was not negatively influencing the way heritage learners were making requests in Spanish, it would be important to replicate this study among heritage learners who are at various proficiency levels. Considering that even the definition of a 'heritage learner' is difficult to concretely determine, due to how non-homogenous this group of learners is, the results might be different for different heritage learners.

Instead of simply not teaching pragmatics to HLs, an idea would be to include them as expert speakers in a classroom. Speaking in an appropriate way according to the context is extremely important for a positive communicative experience.

Hernandez, T., & Borreo, P. (2018). Explicit intervention for Spanish pragmatic development during short-term study abroad: An examination of learner request production and cognition. Foreign Language Annals, 15(2) 389-410. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2057944245?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:primo&accountid=14698.

This study addresses the problem of study abroad students being unable to develop pragmatically correct request-making strategies in Spanish. Before departure, students were given explicit instruction on how to form appropriate requests in Spanish. They were also given specific tasks to perform during their time abroad that were designed to help them improve their request making strategies. Although the students only spent 4 weeks abroad, most did show an overall improvement in their request making strategies, according to the two expert speakers who evaluated them. This is evidence that instruction in the pragmatics of forming requests can have an impact on how well L2 speakers are able to communicate in the target language.

LoCastro, V. (2012). Classroom pragmatic development. Pragmatics for Language Educators: A Sociolinguistic Perspective (pp. 234-264). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203850947

This chapter from a book for language teachers is not focused on Spanish, but it is still very valuable. It goes into detail on why pragmatic competence is important for second language (L2) and foreign language (FL) learners. The author examines nuances of pragmatic development in the classroom and if it is even possible. Finally, LoCastro gives advice to teachers. She explores the following nuances: first language (L1) transfer, classroom input, teachers, materials, learners, sociocultural dimensions, and language norms.

Pinto, D. (2005). The acquisition of requests by second language learners of Spanish. Spanish in Context, 2(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1075/sic.2.1.01pin

The author of this article briefly explores ways in which requests are made in different Spanish-speaking countries and compares them to English. He notes the importance of showing learners the differences between the ways requests are made in the two languages. He also provides multiple examples of regional differences in directness. A helpful list of strategies and downgraders is included, along with an analysis of their use in English and Spanish. Downgraders can be used to modify the head act in a request. Common downgrading devices used in Spanish are: Conditional/past tense (podrías, podías), Politeness marker (por favor & porfas) and Negation (¿No te molestaría sacar la basura?).

Derrin Pinto focuses on beginner language learners and debunks the myth that pragmatics cannot be taught at this level. In this study, power and age were not included because novice learners have been exposed to some, but not all grammatical forms.

Pinto, D., & Raschio, R. (2007). A comparative study of requests in heritage speaker Spanish, L1 Spanish, and L1 English. The International Journal of Bilingualism: Cross-disciplinary, Cross-linguistic Studies of Language Behavior, 11(2) 135-155. https://go-gale-com.libproxy.uoregon.edu/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=euge94201&id=GALE%7CA166988884&v=2.1&it=r.

This study compares the request strategies of three groups: 1) L1 Mexican Spanish speakers, 2) L2 Spanish learners (who were all L1 English speakers), and 3) heritage speakers of Spanish living in the U.S. Though there was some variation in the results, the researchers determined that there was a statistically significant difference in the main ways each group formed requests. The L1 Spanish speakers tended toward more direct structures in their requests, while the L2 learners tended toward more indirectness in theirs, presumably modeled off of English pragmatics of requests. The heritage speakers were more direct than the L2 learners, but less direct than the L1 speakers. This study informs teachers and learners about directness and indirectness when comparing the pragmatics of Spanish and English request strategies.

Placencia, M. (2005). Pragmatic variation in corner store interaction in Quito and Madrid. Hispania, 88(3) 583-598. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20063161?casa_token=k2Dd-qtY6xMAAAAA%3Ah3maK6jBOZmtPx5idOZPRo_cvNj2CFScpzhCqwxySwe3YaIy28JMTmsaPiZ__uGACEbPwSRUmWcp7hNtbZM2EFPaW7cxfexIRAqathy-ByNU63ocDj4&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

This paper presents an analysis of pragmatic variation in corner store interactions, using data from Quito and Madrid. Requests in Quito tend to be more elaborate and interpersonal, with longer preambles than in Madrid. Quiteños generally prefer more personalized service than Madrileños. Similarly, Quiteños may be more people-oriented than Madrileños. Additionally, internal modification occurs more frequently in Quito Spanish, enabling more diversity in interpersonal messages. In Madrid Spanish, speakers may consider each other as intimates, thus having less of a need for internal modification.

Shively, R. (2011). L2 pragmatic development in study abroad: A longitudinal study of Spanish service encounters. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(6) 1818-1835. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378216610003644?via=ihub#bbib0070.

This study focuses on how U.S. students studying abroad in Spain made service requests in places such as shops, restaurants, and banks. Students recorded themselves when making these requests. They were analyzed at different times over the course of the semester. Overall, the students’ request-making strategies shifted to become more native-like over time. The researchers attributed this improvement to both language socialization as well as explicit instruction. This research shows how non-native speakers may improve in the pragmatics of request making in Spanish, even if requests are formed very differently in their L1.

Sykes, J. (2009). Learner Requests in Spanish: Examining the Potential of Multiuser Virtual Environments for L2 Pragmatics Acquisition. 2009_Sykes_J_Learner_Requests_in_Spanish.pdf.

This article discusses one of the primary differences between Spanish and English request strategies: speaker-oriented requests (Spanish) vs hearer-oriented requests (English). According to the results of a prior study in which monolingual Spanish speakers were compared to L2 Spanish learners, some of this orientation tended to carry over from the L1. This meant that the less advanced L2 speakers continued to make hearer-oriented requests in Spanish. In the case of the more advanced L2 speakers, there was a tendency to switch the orientation to speaker-oriented, as a monolingual Spanish speaker would. This study informs one of the primary ideas of requests: hearer vs speaker orientation.

Sykes, J. M. (2018). Interlanguage Pragmatics, Curricular Innovation, and Digital Technologies. CALICO Journal, 35(2), 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.36175

The internet is both a collection of resources and a way for people to communicate. Thus, it can be used as a powerful tool in teaching pragmatics. The author of this article suggests five area in which internet technologies can be used to teach pragmatics. It would be helpful for instructors to read this article if they are looking for ideas on how to use the internet to teach pragmatics.

These include a discussion of criteria for well-researched online curricula and specific examples in various languages, including Spanish. Under 'Classroom Interventions', the authors lists ways computer-mediated communication can be used in the classroom, both synchronously and asynchronously. 'Telecollaboration' is a way for learners to communicate with each other through chat, emails, blogs, and much more. The internet is also a way for researchers to gather learner corpora and conduct other research. Finally, 'Augmented Digital Contexts' is a discussion about social media, hashtags, and more.

Taguchi. (2018). Contexts and pragmatics learning: Problems and opportunities of the study abroad research. Language Teaching, 51(1), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444815000440

This article is not focused on Spanish, but can still be a valuable resource. The author of this paper describes the importance of studying contexts for pragmatic learning. Often study abroad is approached in a simplistic way when it is thought of as having extensive pragmatic benefits to learners. As the author points out, these benefits depend on multiple factors. In studying this context, the author explores the ways in which we approach this context, the exposure to input that is available, and examples of situated practice.

Even though this paper is about study abroad as a context for pragmatic learning, it also includes a detailed study of pragmatic competence. This would be a helpful article for those interested in reading about the history of scholars' understanding of pragmatic competence and how it evolved. Pragmatic competence consists of three elements: knowledge of linguistic forms and their functional meanings, sociocultural knowledge, and the ability to use the two types of knowledge for communication in interactions.

Walters, J. (2006). Strategies for requesting in Spanish and English: Structural similarities and pragmatic differences. Language Learning, 29(2) 277-293. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229695453_Strategies_for_requesting_in_Spanish_and_English_Structural_similarities_and_pragmatic_differences.

Although similar semantic structures are available for constructing requests in both Spanish and English, the differences in pragmatic meanings are significant. Within this theme, this study seeks to compare the grammatical forms of English and Spanish requests with specific regard to politeness in both languages. Drawing on the results of these comparisons, the study also analyzes adult English and Spanish speakers’ perceptions of politeness in requests. The findings suggest that there is a wider range of “polite” requesting strategies in Spanish while more “neutral” strategies exist in English.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON APOLOGIZING IN SPANISH

Resources in this section curated by: Illena Trebont

Langer, B.D. (2011). Teaching Pragmatic Forms in Spanish. Segundas Lenguas e Inmigración.

This study describes an effective way to teach apologies in Spanish. In this study, students were taught about speech acts, how to apologize in Spanish, and completed activities to ensure comprehension of the material in the first two lessons. By comparing pretest and posttest scores, the study showed that students’ apology strategies became more native-like after pragmatic instruction.