Conversational structure (opening and closing) in Non-Lang Specific

Miscommunications

(with a focus on neurodivergency)

PRACTICAL IDEAS AND RESOURCES

Resources in this section curated by: Kira Seretan and Chloe Tacata

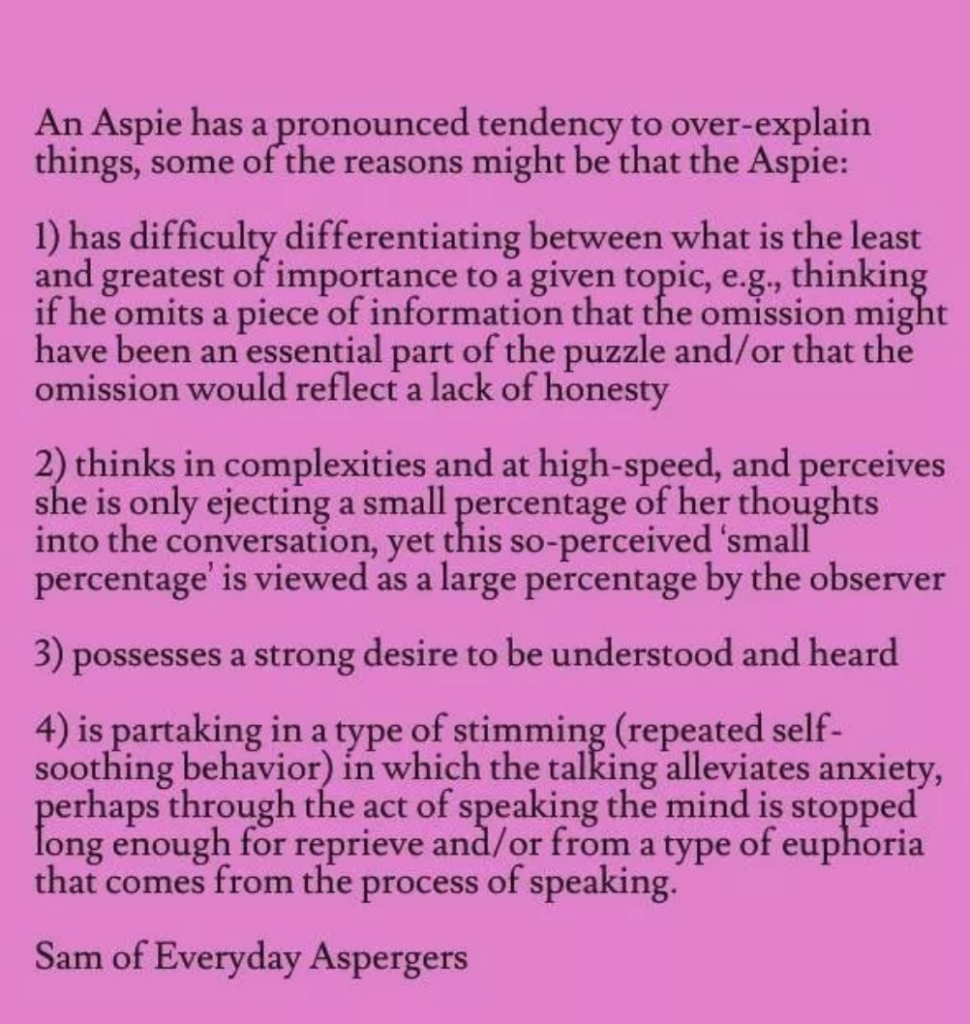

Asperger's Issues | Image

This outlines four major areas where miscommunication or pragmatic mismatching might occur for an individual with aspergers (a mild form of autism). These are identifying the relative importance of various topics, thinking at high speed, but not communicating everything they are thinking, a strong (even overwhelming) desire to be heard and understood, and the desire to stim (engage in repetitive acts with soothing properties for the individual) to relieve anxiety.

Where communication breaks down for people with autism | Article

People on the spectrum often have subtle problems using language or making facial expressions. Pinpointing where those difficulties originate may help ease their social communication.”

Lydia Denworth discusses some of the reasons why communication (based on neurotypical rules) can be difficult for neurodiverse individuals. They acknowledge that these challenges can be difficult to characterize because there is so much variability. Specifically, the article summarized results from a few studies on the use of prosody, facial expressions, and pronoun errors by neurodiverse speakers. In conclusions, the author suggests that differences in these areas of communication are what make the speakers seem “awkward”. The research presented in this article could be used to educate neurotypical individuals to encourage them to be more understanding.

How not to take things personally? | YouTube Video

This video deals with the topic of not taking things personally. While it does not focus directly on neurodivergence, this is an important tool in neurodivergent-neurotypical communication. The directness prominent in neurodivergent communication and frequently preferred by neurodivergent speakers can lead to offense and bruised egos. This video discusses how to avoid the ego taking over and how to avoid taking others' actions and speech personally which can support an individual in a discussion with a neurodivergent individual, for whom direct speech is not personal or intended to be offensive. This can lead to fewer angry disputes and miscommunications.

Unwritten Rules of Social Relationships: Decoding Social Mysteries Through the Unique Perspectives of Autism | Book

This book is by Temple Grandin (see two of the YouTube videos provided in this collection) and Sean Barron. It focuses on many of the unwritten social rules used by (presumably predominantly English speaking) neurotypical individuals and how to decode these “mysteries” through an autistic lense. This can both provide another point of view on day-to-day activities and discussions for a neurotypical reader and serve as a strong educational tool for a neurodivergent individual. This book deals with logic, isolation, difficulties in childhood, communication, and the need for neurodivergent individuals to learn by mimicry (even if they do not receive the support to entirely understand why they are learning what they are learning) in order to “pass” in a neurotypical society. The book description states, “Whether you are a person with autism, a caregiver in the autism community, or just someone interested in an outsider view of society, their powerful stories will enthrall and enlighten you.”

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON HUMOR

Not Language-Specific

Resources in this section curated by: Carla Consolini, Tigre Lusardi, Lorelei Pfeffer

Bell, N. D. (2009). Learning about and through humor in the second language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 13(3), 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168809104697

The author of this article analyzes data taken from previous research investigating the use of humor in a second language (L2), both inside and outside of the classroom (Davies, 2003; Schmitz, 2002; Bell, 2002), to make the case for why using humor in L2 classrooms is appropriate and useful. First language (L1) speakers were shown to support L2 speakers in their (the L2 speakers’) construction of humor. The most commonly occurring type of humor in spontaneous recorded conversations between L1 and L2 speakers was the humorous narrative. This contrasts greatly with the types of humor usually included in classroom settings, which are wordplay and the construction of alternate or imagined scenarios/realities.

The author provides tentative suggestions for effective ways to employ humor in classroom settings. Teachers should be familiar with basic tenets coming out of sociolinguistic humor research such that they can lead explicit instruction and conversations about humor, its construction and its social/pragmatic use. For student activities, the author suggests focused awareness and analysis activities, such as having learners analyze naturally occurring speech found in media or films for presence and type of humor.

Bell, N. and A. Pomerantz (2019). Humor in L2 Pragmatics Research. In Taguchi, N. (Ed.). The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and pragmatics. Routledge.

In this overview of the current understanding of humor and its applications in L2 learning, the authors situate the study and use of humor in L2 and SLA (second language acquisition) research and classrooms by first presenting the central ideas of humor research and then reviewing empirical evidence about humor and L2 development in both previous foundational and more recently published studies.

The three concepts that underlie their arguments are that humor can function to aid L2 pragmatic development, that it can be used as a resource for/in L2 interactions, and that it is an aspect of an L2 that must be explicitly learned.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON MEMES

Not Language-Specific

Resources in this section curated by: Carla Consolini, Tigre Lusardi, Lorelei Pfeffer

Grundlingh, L. (2017). Memes as Speech Acts. Social Semiotics, 1(3), 1-22.

The author argues that memes are speech acts that help people communicate online without having to talk or write to each other directly. When memes are being made by their creators, semiotic choices are made about the internet community that the meme will be shared in. In this research study, several macro memes (images with text) are analyzed, interpreted and categorized under different speech acts. The authors conclude that memes can be used for communication and therefore are part of speech acts, and these memes can be transformed over time acquiring new meanings. However, understanding and communication through memes can be complicated; a meme needs a community that understands it since its conception, or has enough background knowledge to understand the ways it is being used.

Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2018). Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23, 294-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy016

The authors of this study investigated how templates of some memes were used across different parts of the world in order to shine light on cultural differences regarding digital means of globalization. The authors gathered and analyzed a sample of the top 100 templates of memes (as of 2017) in English, Spanish, Chinese, and German. They discovered that even though memes are heavily influenced by Western or American culture, locally rich memes arise and are also strong. The authors conclude that memes are politically or socially conservative, but with a high degree of emotional expression.

Wiggins, B. E., & Bowers, G. B. (2015). Memes as genre: A structurational analysis of the memescape. New Media & Society, 17(11), 1886–1906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814535194

Wiggins and Bowers illustrate the history of the meme and how it has impacted the digital landscape, especially participatory digital culture, when transmitted for discursive purposes. They argue that memes are digital artifacts, which allows them to take up physical space within the virtual world. The article focuses on macro images of memes, but touches on video and text memes as well. However, the analysis of memes lacks a theoretical framework, which would make research more meaningful.

Yus, F. (2018). The interface between pragmatics and internet-mediated communication. Applications, extensions and adjustments. Pragmatics and its Interfaces, 267-290. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327215174_The_interface_between_pragmatics_and_internet-mediated_communication_Applications_extensions_and_adjustments

Yus discusses how pragmatics of communication on the internet comes into play when interlocutors create new rules. Yus cites two seemingly contradictory ideas, which is that pragmatics do not matter on the internet and the internet is a breeding ground for new forms of pragmatics. People often have difficulties conversing, which leads to pragmatic failures. Often the constraints of internet communication include difficulty transmitting tone, context, and facial expressions of both the sender and receiver of a message.

Zenner, Eline, & Geeraerts, Dirk. (2018). One does not simply process memes: Image macros as multimodal constructions. In Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research, 167-194. Mouton de Gruyter; Berlin/Boston. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/59541/1/9783110586374.pdf#page=174

In this article, Zenner and Geeraerts examine image macros from Internet memes and how the rigid frame allows for creative wordplay within the understood structure of the meme. They define an image macro as a visual that combines elements of jokes and wordplay, while being in itself a joke. They define the meme itself as a prototypically-structured multimodal construction. However, the memes they cover are a top-text, bottom-text style meme, which may not cover all types of image macros in today’s meme landscape.

ACADEMIC RESOURCES ON MISCOMMUNICATIONS

(with a focus on neurodivergency)

Resources in this section curated by: Kira Seretan and Chloe Tacata

Bergen, B. and Trott S. (2020). When Do Comprehenders Mentalize for Pragmatic Inference? Discourse Processes, vol. 57:10, pp. 900-920, DOI: 10.1080/0163853X.2020.1822709

This study focuses on the mechanics with which inferences are made. This is valuable in a number of ways as it relates to cross-neurotype conversation and communication. For the purpose of this study “Mentalizing correlates with task performance when comprehenders are asked to sample and report mental state information (Experiment 1b) or when given mental state information explicitly and asked to make an inference (Experiment 2, Explicit),” (Bergen & Trott, 2020).

Mentalizing is often difficult for neurodivergent individuals and understanding how it works, and the difficulties that neurodivergent individuals might be having, can help a neurotypical individual to understand what they might be miscommunicating in a conversation. This kind of understanding of their own strategies can make a neurotypical individual more aware of the choices that they are making and give them an ability to co-construct interactions to avoid miscommunication. Furthermore, this article can also help neurodivergent individuals to understand, if not necessarily the actual inferences that they might be missing, what they are misunderstanding and that there may be something that a neurotypical individual is trying to tell them that they are not realizing. Knowing where there can be miscommunications is very important for avoiding them in conversation.

Shlomo B., Rajwan O., and Tal S. (2021). Conversational Categories and Metapragmatic Awareness in Typically Developing Children. Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 172, pp. 46–62.

This article focuses on metapragmatic awareness in children by asking them questions about video-recorded conversations (the assessed metapragmatic test). The videos were split into two categories: turn-taking mechanisms and dialogue cooperation skills. Each participant was asked if there was something wrong with the conversation; if they could identify what was wrong; why it was wrong; and what could have been done instead. The experiment participants in this study were all typically developing children aged 4 -10 and their performance on the tasks was compared with an adult control group. The researchers found that as age increased, the participant’s scores of the assessed metapragmatic test increased. This finding aligns with similar studies done with English-speaking participants. This study also found that the scores for the turn-taking skills category were higher than the dialogue cooperation skills category. This indicates that awareness of turn-taking skills developed earlier, possibly because of their simplicity.

Even though this article did not deal with metapragmatics in use, directness, or neurodivergence, it gives some background on what kinds of metalinguistic rules children may already be aware of. It also provides an introduction to when and how long it may take to develop metapragmatic awareness. One takeaway from this study is that it seems that the children in this study had the most trouble identifying why certain interactions were inappropriate, despite identifying that there was something wrong with the conversation.

Engelhardt, Paul, et al. (2017). Speaker-Versus Listener-Oriented Disfluency: A Re-Examination of Arguments and Assumptions from Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 47, no. 9, pp. 2885–2898.

This study investigates disfluencies in high functioning forms of autism spectrum disorders (HFA) by analyzing disfluencies produced by HFA speakers and neurotypical speakers. The researchers looked at the four main types of disfluency: filled pauses, unfilled pauses, repetitions, and repairs. They found that HFA individuals produced more repairs and unfilled pauses than the typically-developing group. The researchers believe that the increased rate of unfilled pauses was due to slower memory retrieval in individuals. They also conclude repair disfluencies are speaker-oriented (due to speaker-oriented factors).

This article provides some information about ASD and disfluent speech. While most of the resources are focused on directness and misinterpretations, it is important to understand that neurodivergence can affect verbal skills in many ways.

Martin, Gary E, et al. (2020). Longitudinal Analysis of Communication Repair Skills across Three Neurodevelopmental Disabilities. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 26–42.

Gary et al. studied the communication repair skills of individuals with fragile X syndrome with and without autism spectrum disorder, idiopathic autism spectrum disorder, down syndrome, and typically developing children over time. Their findings suggest communication repair skills may not be as limited by language and cognition as previously thought. They also found significant sex differences in the development of communication repair skills. The males that participated in this experiment demonstrated a decrease in inappropriate and suprasegmental strategies with age. On the other hand, the females in this experiment with FXS-ASD, FXS-O, and DS became more non-responsive with age. These sex differences seemed to be significant especially in children with FXS-ASD. There were also observations that indicate that individuals with different diagnoses had different challenges. For example, the males with FXS-ASD did not increase their use of meta-commentary, while the other groups did.

This article demonstrates that some pragmatic skills can be improved over time, with age. The authors noted that the improvement of some of the older children could have been a result of intervention, but these results still show that communication repair is malleable. These results also show that it is important to keep in mind that neurodiverse individuals face different challenges and that the effectiveness of interventions depends on the individuals. With this in mind, some of the interventions and strategies presented in our project may not be applicable to all neurodiverse individuals.